From boots for dogs to Diana’s wedding dress: my stepdad the great inventor

Douglas Boyd Buchanan spent a lifetime in search of the great innovation

I sat in the corner of the room, taking notes as my stepfather emptied the contents of his scruffy holdall onto the table.

“This,” he said, “is for cutting parcel tape.” The bankruptcy interviewer looked at the lump of metal in his hand, covered with tape and pencil marks and held together with mismatched metal pins, and frowned. My stepfather kept talking, explaining how his cutter was better than a traditional pair of scissors or a knife when it came to slashing open packages. He looked around for a piece of tape to demonstrate, couldn’t see one and so moved on.

“This is a prototype coat-hanger,” he said, pulling out a plastic coat-hanger whose hook had been cannibalised with a piece of what looked like bent wire. He waved it around as he talked, telling the interviewer how normal coat-hangers have stiff hooks whereas this one would correct itself no matter which way it faced when you tried to hang it up.

Her expression turned to pity, and she wrote some notes on her form, avoiding his eye. My stepfather, in full flow, didn’t even notice, pouring more and more bits of metal onto the desk, each one looking sad and out of place and more and more half-baked than the last.

She can’t see it, I thought, as I watched them. She’s looking at this small, wiry, chatty man with his craggy eyebrows and his Parkinson’s shake and seeing every single madcap inventor stereotype she’s ever come across – Professor Branestawm has a lot to answer for – and not seeing how very clever he is, or how every single one of these ideas he has actually works.

On this occasion the interviewer’s bemusement would work in our favour, because she decided that a combination of his illness and his inventor ‘madness’ were to blame for the fact that he didn’t pay his taxes and so wrote off his debts without question, where a more sane-looking person might have had to pay something back.

Whenever you mention the word inventor to a regular civilian they get this look in their eye, and you have to decide how much to explain. I use it as an icebreaker at parties sometimes, “Hey, guess what, my stepdad is an inventor,” just as something to say, but also as a test. How open-minded is this person? How much are they willing to listen? How quick are they to judge?

They almost always come back with the same question: “So what did he invent?” and I look at them and think, “Where do I start?”

My stepfather, Douglas Boyd Buchanan, was born into a wealthy Glasgow household in the 1930s. His grandfather was a renowned architect who designed many of the cinemas in the city, and his father was involved in the design and build of the wooden Mosquito plane that was used in World War II. As a child, stubborn, creative and full of fun, Douglas raided his father’s drawers and stole most of the negatives of the secret plane design process to cut up and use as flights in his arrows. He regularly got into scrapes, including for getting his own planes stuck in the wires of the Glasgow trams. He went to art school and also did an engineering night class, and his first job was as a draftsman drawing boiler designs for ships, eventually travelling across Europe designing and fixing boilers and other machinery, including for motor racing company Spirit.

By the time my mum met him in 1990 he was twice-divorced and living in Shropshire, where he had moved his small workshop and was working full time as an inventor and designer, designing, amongst other things, fairly way-out looking lamps, as well as jewellery and buckles that he sold to any company brave enough to take them.

Douglas made a small gold horseshoe that was sewn into Princess Diana’s bodice for good luck

I asked bespoke shoemaker John Lobb how Douglas came to make all the buckles and other fittings for his business. Had he just walked in off the street and started talking? Lobb laughed and said he didn’t remember but that sounded about right. Jasper Conran, Betty Jackson and Bruce Oldfield also used Douglas’s designs.

It was through these fashion connections that Douglas came to know the Emanuels, who designed Princess Diana’s wedding dress. He was commissioned to make a small gold horseshoe that was sewn into her bodice for good luck. He gave me the prototype horseshoe as a gift. I have, shamefully, lost it. Our life was always awash with pieces of metal and odds and ends of Douglas’s ideas and at the time this was just another little piece of brass in a drawer somewhere. Since his death I have, of course, torn my flat apart looking for it, but it is long gone.

As an early teenager, I spent a lot of time in Douglas’s workshop, either after school, waiting for my parents to finish work to get a lift home, or in school holidays. I began to earn income for helping out, joining in on the assembly process, or helping to package completed items ready to send. It was a small, two-roomed space on the ground floor of a converted mill, one room filled with machinery including hand-presses, drills and polishers, the other a light “studio” space with Douglas’s desk and workbench, as well as tables for the small team of people, sometimes as many as five including me, to work as needed. At that time he was making and selling Spectangles, a small device he had designed to hold your glasses, for Lakeland; Bookmindas, a device for holding your book open that he sold through the QBD catalogue; as well as all the special buckles for the Metropolitan Police.

Douglas made various different buckles for the Met, thousands of them, all made in collaboration with a leather specialist so that they were strong enough that a police person could use their belt to pull up a person who'd fallen off a bridge/cliff etc. Their old buckles were cast metal which sometimes used to shatter in the cold so Douglas's were much better. He made all the uniform dress buckles, which were just nice, plain standard looking silver buckles – D-shaped for women, curved oblong with a central cross bar for the men. However he also made all the equipment belt buckles for them, which were more specialist. If a police person is called to an emergency in a hurry they need to slip their equipment belt on quickly, but normal buckles are fussy to do up. They had experimented with those squeezy snap ones you get on lots of strap fastenings, but they found that members of the public would reach out and squeeze them, dropping all their equipment on the floor and then running away. Douglas designed ones that looked like straight forward buckles on the front, but had hidden hooks at the back so they were quick to put on and off.

Things like belt buckles – small, in large-ish numbers, were the bread and butter money that helped fund the research and development time for the bigger ideas.

Douglas’s ideas came from a mixture of thoughts he had whilst walking around in the world; my mum once told me about a holiday to Lyme Regis where he spent hours accosting people on the street with wheelchairs and mobility aids to ask about how they worked for example, an exercise that led to an ongoing project that included walking sticks, crutches and walking frames; but also through specific commissions.

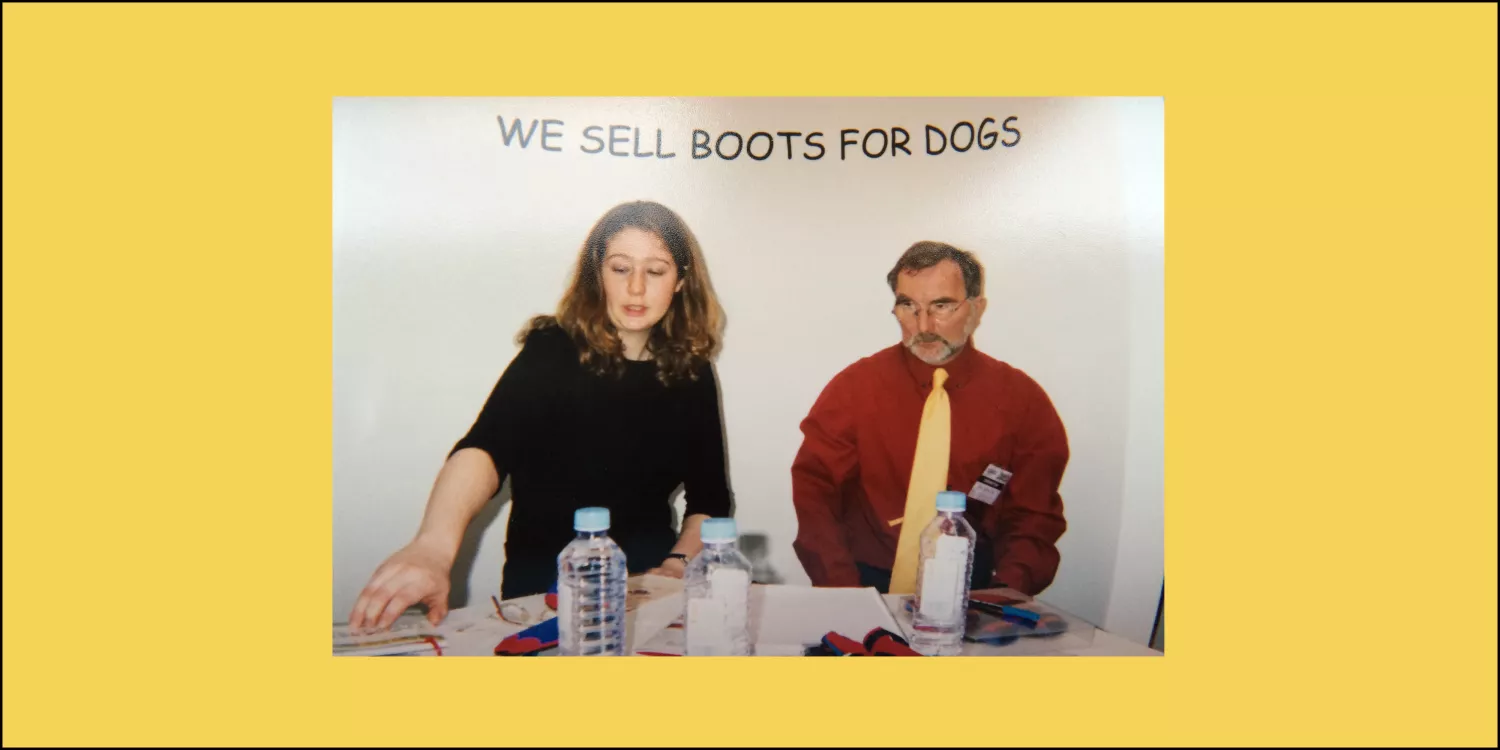

Dogs have smaller back paws than front paws, so each dog needs two different-sized pairs of boots

One commission that came Douglas’s way was from the Prison service. They have a dog division and lots of their dogs were getting glass in their paws in riots, so they wanted someone to make them protective boots.

Douglas, a dog-lover, set to work, using our two pet dogs as somewhat bemused models. Dog boots always get a bit of a laugh when I bring them up, but they are very commonplace amongst police, prison and rescue services; if you look closely at reports of the Grenfell Tower disaster, for example, you will see search and rescue dogs wearing boots as standard.

Douglas’s were the first. His were made from Neoprene (wetsuit material) as it is a fabric that stretches in all directions rather than just one way to a grain, meaning that it can cope with the way a dog’s foot flexes and retracts as it walks. The rubber soles were designed to have the same amount of slip as a dog’s natural foot pads, because otherwise the dog either gets stuck or slides too much, making walking difficult.

We discovered that a dog has smaller back paws than front paws, meaning that each dog needs two different size pairs of boots rather than four the same. At some point the press found out about the boots, and the public went nuts for them. Douglas, charismatic and funny, was always up for interviews and TV appearances, and he appeared on Eureka!, a pop science show presented by Matthew Kelly, triggering hundreds of letters from individual dog owners looking to buy boots for their own beloved pets. Our most famous customer was the Queen, whose corgis had issues with their paws and needed help. Douglas recalls talking to one of the Palace staff on the phone and suddenly hearing “the voice” as the Queen personally told him that she thought his boots were marvellous.

Douglas had ideas coming out of his ears, but each one needed to be sold to someone who would buy them in sufficient numbers to make them financially viable. He also needed a business capable of making products in those numbers. This didn't always go well. One project, a new type of body armour, saw Douglas end up in court with a company he believed has mishandled a contract. Though we won the case on principle, our solicitor-advocate was no match for the corporation’s army of Armani-clad lawyers, and we lost our house.

With the dog boots, they were expensive to make on a small scale, because so many different sizes meant making individual tools for each specific size, and selling individual pairs through the post wasn’t going to work, so Douglas took on a partner to work on sales, a man who increasingly showed himself to be so shifty that eventually all ties had to be cut with him.

What is it about inventors? What is the magic that charms us?

In 2002 Douglas was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, a crushing blow that would eventually make it impossible for him to work. It was agreed that instead of these commissions, and churning out more and more new ideas, he would focus on something he had been thinking about for many years, the final push, his favourite project, the underwater bike. Always interested in sports and how the body works (Douglas’s golf putter and how the golf world reacted to it is a whole other story), the underwater bike came from his particular love of snorkelling. In interviews he told a standard story of being blown off course and getting exhausted swimming back to shore, and how this small drama got him to thinking about how it would be better if he had a ‘bike’ or similar to travel on. Neutrally buoyant, meaning that it hangs in the water, with handlebars for steering and a propeller instead of wheels, Douglas’s playful but fully functioning underwater bike won prizes at an inventions fair, and attracted a lot of interest. Sadly, none of that interest led to sales before he became too ill to drive the project further. Another idea that currently sits in our greenhouse gathering spiders.

Douglas died last year, with no money and nothing much to show for his amazing talent except a stack of notebooks, a large collection of metal objects and a folder full of press clippings, another cautionary tale for anyone who is thinking of doing anything even a little bit out of the ordinary.

What is it about inventors? What is the magic that charms us? Everyone is an inventor, Trevor Baylis once said to me. He started listing off all the inventions that we don’t even think about. Another inventor told me about what a blissful process it is, a safe place from the world where it’s just you and the problem you have to solve, a place full of possibility. He confessed that it had also caused him trouble in his life, choosing his inventing work over nurturing relationships or money.

Douglas certainly loved his work, and looking through his notebooks now it’s clear that, while he took it very seriously and worked consistently at it every day, it was also a place where he could play, with ideas, with outrageous thoughts, with possibilities, where trying something out and failing was just another step in the game.

It also protected him from some of the big problems in his life. “Didn’t you ever worry about the amount of money you owe?” The bankruptcy administrator asked Douglas, when she got to the final part of the form. “Oh no,” he said. “All I needed was for one idea to take off.” He had so many.