The hidden history of the Conservatives' first ethnic minority MP

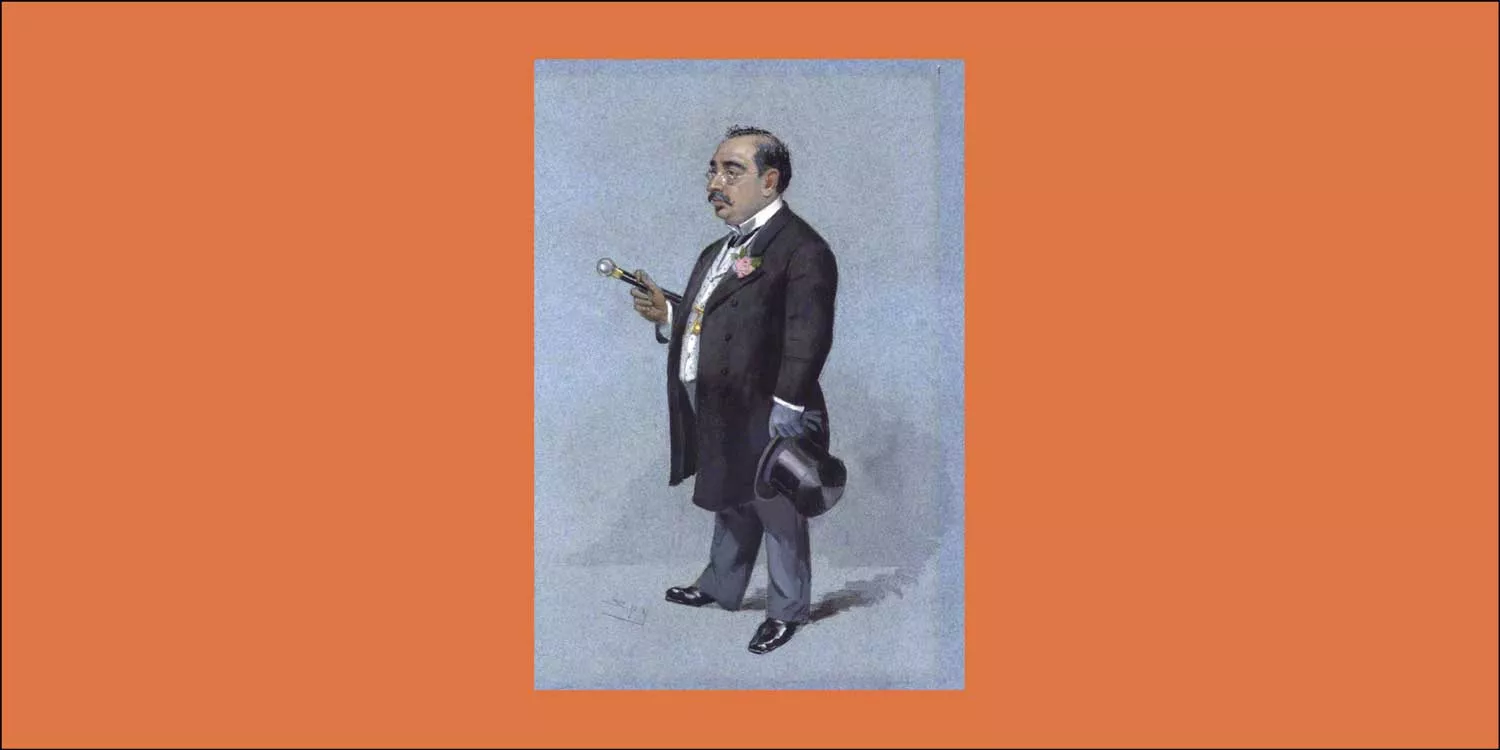

Mancherjee Bhownaggree was a complex figure

This article originally appeared in issue 2 of the Little Atoms magazine. To find similar articles and buy a copy, please click here.

The British empire made Mancherjee Merwanjee Bhownaggree. The son of a Parsi merchant, his rise to the House of Commons, knighthood and prominence in English high society came from his lifelong passion for the empire. Yet his support for imperialism has made him one of history’s overlooked figures, both in British and Indian history. While Bhownaggree’s generation of Indian politicians such as Gandhi – with whom he studied– and Dadabhai Naoroji, known as the Grand Old Man of India, are heralded, very little is known about Bhownaggree, the first ethnic-minority Conservative MP.

While Naoroji served just three years in parliament, as Liberal MP for Finsbury Central between 1892 and 1895, Bhownaggree won two election victories in Bethnal Green North East in 1895 and 1900 and was a parliamentarian for 10 years. Since his death, he has merited only a few footnotes in histories of black and ethnic minority people in Britain.

Bhownaggree stood on an anti-migrant, pro-Empire platform aimed at the East End working class

An immigrant himself, Bhownaggree stood on a staunchly anti-migrant, pro-empire platform that spoke directly to the English working class. His Liberal opponents lost against a man they characterised as the “member from Bombay” who was wildly popular among his poor constituents.

The East End that hosted Major Gordon-Evans and his antisemitic British Brothers League elected an Indian to parliament. Bhownaggree sat on the Aliens Act committee to reduce migration, but he advocated more Indian migration to South Africa.

Mancherjee Merwanjee Bhownaggree was born in Bombay in August 1851. He travelled to Britain in 1882 to study law and was called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn in 1885, one of 12 Indians who passed the examination. A year later, the Maharajah of Bhavnagar requested he return to India to oversee the reorganisation of the state’s constitutional and legal affairs. Bhownaggree soon returned to England, and he got involved in politics in 1892 helping his fellow Parsi, Dadabhai Naoroji, win election to the House of Commons on a Liberal ticket in Finsbury. Bhownaggree became determined to win a parliamentary seat himself, and in 1894 found himself the third-choice Conservative candidate for Bethnal Green North East. After the other Conservative candidates dropped out, deciding that beating the popular Liberal radical MP George Howell was too big a challenge, Bhownaggree became the candidate.

Howell was a trade unionist and a strict Christian. In his working-class constituency, he was popular for his support of trade unions and his role in the campaign behind the 1867 Reform Act. No one expected him to lose his seat in the 1895 general election, least of all the local Conservative party. Bhownaggree was undeterred. He ran a vibrant campaign with a direct appeal to working-class voters focussing on immigration, bread and beer, opposition to both Irish and Indian home rule, and a strong nod to imperialism:

“In this cause of Liberty –

And your bread and beer,

Come, vote for Bhownaggree – And uni-ty.”

Yet it was immigration that got the Unionist candidate from India over the line. Bhownaggree went on the attack, telling local newspapers he opposed “competition from Pauper Aliens, and the Rates from being burdened by them”. The aliens he was referring to were Jewish refugees fleeing pogroms in Russia and Poland. At their peak they numbered around 150,000 people, many of whom settled in the East End of London. In their wake, antisemitic anti-migrant organisations such as the British Brothers League, led by Major Evans-Gordon MP, and the British Industries, Trade and Labour Defence League, won massive support. Bhownaggree assiduously courted their votes. He addressed both organisations in a builder’s yard, and assured them he would back any anti-alien legislation proposed by Major Evans-Gordon to cheers. None of the assembled thought it contradictory that they were backing a politician from India to tackle migration. Nor did Major Evans-Gordon, who grew close to Bhownaggree.

Bhownaggree was an early Tory supporter of women’s suffrage

David Cannadine’s study Ornamentalism gives us a clue why. For the Victorians, class meant a lot more than race. Jewish refugees, “the scum of Europe” according to the Brothers League, were low-class; Bhownaggree, the suited Indian gentleman, was upper-class.

Howell lost to Bhownaggree by 160 votes. Howell was shocked at his loss. He told the local newspaper: “I was kicked out by a black man, a stranger from India.” But Bhownaggree was not a stranger for long.

After his election, Bhownaggree got to work locally, committing to the building of public baths and asking questions in parliament for his constituents. He was an early Tory supporter of women’s suffrage – and many of his most enthusiastic supporters were female conservatives – leading his Liberal opponent at the next election to launch a misogynistic attack on the “witches of the Primrose League”.

At the 1900 election, Bhownaggree doubled down on his patriotic platform. The Eastern Post and City Chronicle quoted him telling voters: “They could not do without their colonies. These were essential to their very existence as a nation.” His campaign was almost entirely on imperial matters, in a seat with little connection to empire. His Liberal opponent, Harry Lawson, tried to use Bhownaggree’s avowed pro-empire platform against him, chiding: “He did not want to be a member for the universe, or to be member for Bombay – but the plain member for Bethnal Green.”

Bhownaggree didn’t budge. His campaign slogan “Into one Imperial Whole!” was complemented by election speeches almost entirely about matters of empire, particularly the Boer war, then at its height. East End Conservatives went door to door in Bhownaggree’s constituency telling voters that Lawson had a sign in the window of one of his dwellings stating: “No English need apply”. Lawson accused his Tory rival’s agents of telling voters he had Jewish antecedents, warning Bhownaggree as an Indian that Englishmen did not like “hitting below the belt”.

Wrapping Bhownaggree in the Union flag worked. Lawson faced indignity after indignity. Voters poured urine and faeces over him in the street, and two boys “apparently of Jewish persuasion” followed him around canvassing throwing potatoes at him. Bhownaggree triumphed, increasing his majority. Marxist historians, who dominate understanding of how the Victorian working classes understood appeals to patriotism, have attempted to write off Conservative electoral support by pointing to evidence that the Tories attracted respectable semi-skilled working-class voters, but Bhownaggree’s majority in Bethnal Green was based on a broad coalition of voters – skilled and unskilled. His election success shows real public support for imperialism. His electoral run came to an end in 1906, when the Liberals routed the Conservatives (their worst-ever election defeat) on a platform of free trade against the protectionist policies of the Tories. Bhownaggree retired from parliamentary politics a local hero. Bethnal Green North East and its successor seats never again elected a Conservative.

The Madras Standard called him a colourless MP

In spite of his anti-immigrant stance, Bhownaggree believed the British empire should act without prejudice or racism. He took public pronouncements against discrimination in the empire at face value and used his status to defend the rights of Muslims in India and other minorities. When he suspected Sydney’s Port Authority had been racist in their treatment of Indian seamen, he raised the matter in parliament. Although he thought the English had higher motives, he thought continental Europeans and their descendants were racially prejudiced.

His belief that other European powers were more prejudiced that the British inspired a lifelong Teutonophobia that became particularly notable after the outbreak of war in 1914. In aid of the war effort, Bhownaggree in 1916 wrote “The Verdict of India”, a pro-British propaganda piece for an Indian audience urging their support. At the heart of it is a full-on attack on German racism as represented by an essay by Dr Hans Delius describing the British use of soldiers from the empire whom he deemed “savages”. Bhownaggree thundered that “the German cannot divest himself of his arrogance and racial and colour prejudice” – unlike the British army, where the “swords of valiant Rajahs” were held next to the guns of British Tommies. British rule guaranteed “liberty and thought and speech”; the German’s were autocrats. “Notions of liberty are foreign to the German mind”, which is why “German colonial enterprises [were] a dismal failure”.

For Bhownaggree, the British were the least-worst colonial power. If India had to be dominated by a foreign power, at least it had been conquered by a power that respected minority rights. He compared the relative peace of India under British rule with the lawlessness of Afghanistan. The Afghans, in his view, only enjoyed “the independence of barbarians… Their independence meant a lawless freedom to cut each other’s throats.”

His enthusiasm for empire came at a cost to his reputation in India. Opponents called him “Bow-and-agree”. On his return to India after his election, he faced slurs from a hostile home-rule press. The Madras Standard called him a “colourless MP”.

The Prabhakar newspaper went further in an editorial, saying Bhownaggree’s supporters were attempting to “whiten” the MP, adding: “You can not make white black.” His reputation never quite recovered. While only once elected to the House of Commons, Dadabhai Naoroji has a statue in the middle of Mumbai.There are no statues, plaques or even adequate biographies of Bhownaggree. His support for empire, as an Indian Tory, means he has become a puzzling footnote of history.

Bhownaggree said that if England were ever to lose her empire, he “might as well give up battling with the world, go up to the mountain-top, say his prayers and live in peace and retirement for the rest of his life”. He died in 1933, spared the indignity of seeing the sun finally set.

Buy Little Atoms issue 1 and 2 together for £15