Making work into an artform

The Artist Placement Group had radical ideas about putting art at the centre of everyday life

Artists have a long legacy of getting wrapped up with politics and social issues.

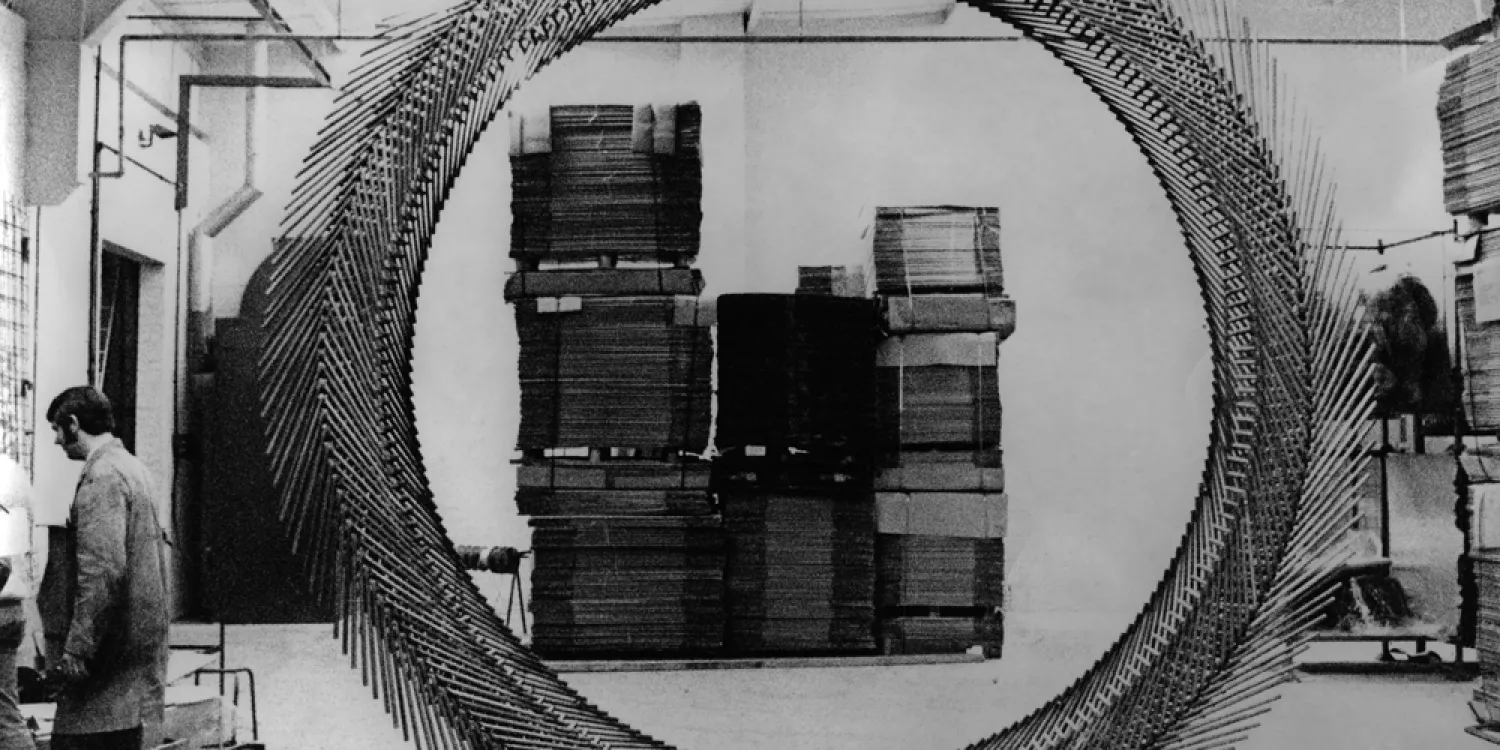

But the most radical incidence of artists attempting to change society at a political level began in the 1960s, when a group of conceptual artists started working in various government departments. Inside the walls of the British civil service and industry, the practice saw artists attempting to infiltrate the British social and political landscape like we’d never seen before.

The practice, known as “least events”, was an attempt to bridge the gap between society and art by physically inserting artists into businesses and corporations, in the hope that by giving them a contracted position their presence would have a lasting impact on the institution and it’s employees. High-ranking trustees such as Tony Benn MP (then a cabinet member) and Frank Martin, the head of sculpture at Central Saint Martins and the then Director of the Design Council, played a significant part in securing funding and assignments for the artist agency.

The collective, Artist Placement Group, was set-up in London during the 1960s, by couple John Latham and Barbara Steveni. Latham had started to produce some controversial works, that sometimes got him into trouble. In 1966, whilst working as a part-time lecturer at Central Saint Martins School of Art, he and his then student Barry Flanagan borrowed a copy of Clement Greenberg’s seminal text Art and Culture from the university library. Later, during a house party, Latham and Flanagan gave each guest a page torn from the book and asked them to chew it. The chewed paper was then collected, fermented, distilled into alcohol and placed in a vial. Latham returned the vial to the library when the overdue book was finally requested and subsequently lost his job.

John Hill, the Education Officer at the studio home of John Latham, now a museum, explains the concept behind CHEW as; “A response to Greenberg’s formalist ideas that still dominated British art schools, and a riposte to Greenberg’s comment that British art was in ‘too good taste’. Latham and Flanagan wondered what Greenberg tasted like.”

During that period, artists universally were beginning to explore new, innovative ways of exploring arts and science. In America, the artist collective Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T) founded by Billy Klüver, and Fred Waldhauer - both electrical engineers at Bell Telephone Laboratories, and the artist Robert Roushenberg, were gaining recognition for facilitating the work of artists who wanted to create avant-garde work using new technologies.

In 1968 APG set about organising their first event, the Industrial Negative Symposium in London, which included Klüver and E.A.T. This collaborative process slowly turned into a sort of artists’ agency, and APG began setting-up their placement scheme. One of the artists who undertook an APG placement was Stuart Briesly. Breisly was an active member of APG from 1967-71, but after becoming disillusioned with the group’s ideals of engineering policy at a direct level, he handed in his resignation. He felt that Latham’s ideologues were not sustainable. The group’s desire to dramatically reshape and direct the county’s politics was no longer about exploring artistic practice but about dominance and control.

Brisley undertook one placement with APG, at Hille furniture factory.

“At Hille, I first worked on the shop floor. I looked around the different departments of the factory, but what appeared to be the most different was the polishing workshop, that’s where I chose to work.” Explains Brisley.

“I had to get to know the workforce, which was difficult. Hille furniture were making interesting products, like the classic Bauhaus chairs, but the people working on the factory lines had no idea.”

After experiencing a disconnect between the workers and the end product, Brisley set about trying to change the working environment. After speaking with management, he came up with the idea of encouraging the employees on the polishing floor to decorate their machines, in an attempt to engage them in the creative process. The end result was a series of heavy-duty machinery painted with the colours of their favourite football teams.

What began as a utilitarian endeavour ended abruptly, when Brisley realised that APG had bigger ideas for the collective, as Latham’s ideologies were revealed to be driven by political motives. One example was an internal memo from 1970 suggested that APG were attempting to redefine the very notion of an artist by renaming themselves “environment” or “concept” engineers.

Under the direction of Steveni, the group began using their contacts to secure placements in industry; from the National Coal Board, Esso Petroleum Co Ltd, and British Airways to the Intensive Care Unit of Clare Hall Hospital, London Zoo and Broadmoor. The aim was to directly control their impact on society, rather than merely comment on it from the confines of a gallery.

Arts and Economics

In 1971 APG unofficially moved into the Hayward gallery during the exhibition Arts and Economics, and began arranging interviews between industrialists and artists to question the new role of the artist in society. The Arts Council decided that the organisation was more concerned with “social engineering” than with “pure art’ and immediately cancelled its funding.

After a short hiatus in the aftermath of the Hayward exhibition, APG reformed in 1973 and began moving into politics by setting up placements within government departments, hoping to infiltrate the heart of the country’s political machine. The group placed an ambiguous advert in Time Out London, stating that a “number of possibilities have arisen for artists within various organisations from short-term projects to long-term associations”.

This rise in the collective’s political ambitions resulted in a series of disagreements. APG disbanded, only to re-emerge in 1989 later as Organisation and Imagination (O+I), but its impact on artists’ roles in industry have remained.

E.A.T went on to promote disciplinary projects across arts and technology right throughout the latter half of the twentieth century, such as international aid programmes and telephone assistance lines for artists wanting to work with new technologies run by engineers from E.A.T. offices. Bell Telephone Laboratories have continued to work with ground-breaking technologies and have won a total of eight Nobel prizes, including Eric Betzig who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2014 for his work in chemistry, which he began whilst working at Bell Laboratories.

Another of APG’s associates was Dr Professor Reimut Jochimsen, Minister for education and science in Germany, who helped set-up a German counterpart for the APG model, with the desire that it “becomes common practice for all large organisations to have a realistic economic relationship with artists, equivalent to other professionals'.

Last year, it was estimated that the UK’s creative industries accounted for more than £71.4 billion per year to the UK economy – generating around £8 million pounds an hour. With unprecedented fiscal power the arts are entering a new era of influence, yet despite their ever growing economic clout, nothing will ever be as provocative as contracting an artist to travel around on shipping cargos with Ocean Fleets for 18 months only to intentionally throw the end result overboard, no questions asked, with the corporation footing the bill.