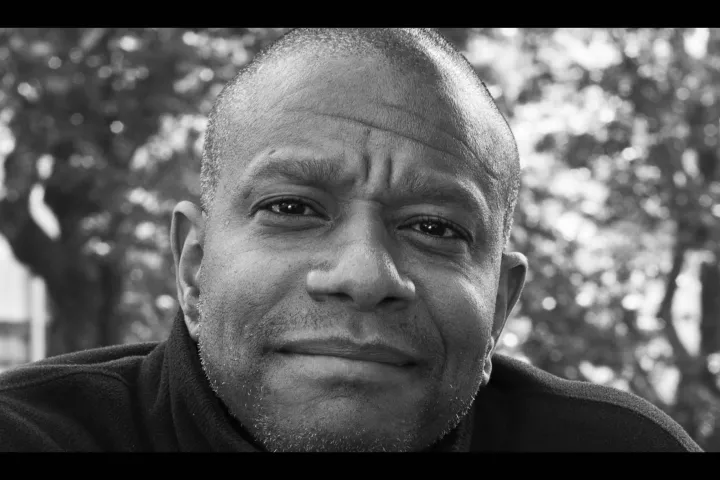

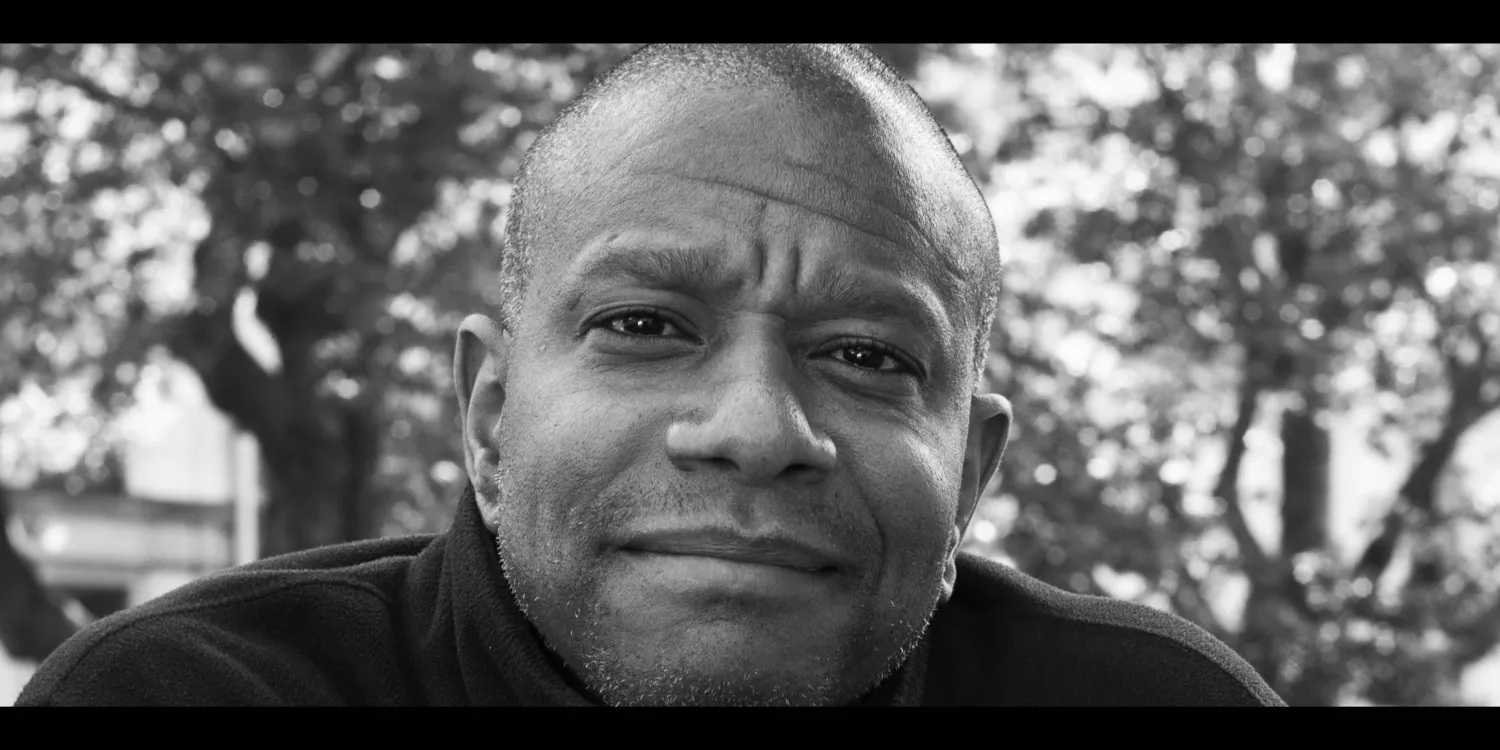

Paul Beatty on place, race and human psychology

Shortly before winning the Man Booker Prize 2016, Paul Beatty sat down with Neil Denny at Watersones Piccadilly in London to talk about his novel The Sellout

Shortly before winning the Man Booker Prize 2016, Paul Beatty sat down with Neil Denny at Waterstones Piccadilly in London to talk about his novel The Sellout

How would you describe what The Sellout is about?

Plot wise, it's about a town that gets erased off the map. A small town called Dickens in southern California gets erased off the map. It's a blight to the real estate boom, and a guy who lives there and one of his neighbours go about trying to put the town back on the map by doing some crazy things.

I had a general frustration about how people were talking about social issues like race. There's a bunch of stuff in the book that's little grains of things that I witnessed or heard. I was just trying to tell a story about a small place that was very representative of the country as a whole.

Dickens is a fictional place. But what's interesting about it is, as well as it being a suburb of LA, it's rural. Me, the protagonist, lives on a farm that's in the inner city. Is that a thing that existed?

I was born in Santa Monica in 1962 but grew up in Los Angeles. I went to school on the East Coast, and people would say, "Where are you from?" And I'd say, "I'm from LA." White kids would go "what?" They didn't know that black people were in California. Then when gangsta rap started, there was a certain type of black person that was in California.

Compton's this unique place. It has a reputation of being this really dastardly place. When I was younger it was actually a place of very middle class sort of well to do African Americans. So it's interesting how the place has changed, and how the neighbourhood sees itself has changed. And now, the community's almost all Latino. (I'm going a long, round about way of answering your question.)

When I was younger my mom would drive us. There were these riots in LA, the Watts Riots in 1965, and still to this day they have a parade. And it was the only thing black our family ever did was we would go to the Watts parade every year, and we had to drive through Compton. When I was really small, you would go through Compton, you would see black people on horseback in the streets, going to the store. It just stuck with me. And then, the only other time I would see people on horseback in LA was in these rich neighbourhoods, because she would take us also to see polo matches. And that was in the Palisades, a pretty much all white conclave in LA.

My sister teaches in Compton, and one of my best friends is a principal in Compton. So I would go visit them, and you're driving through Compton, which has this reputation that you can't shake because of all the hype, and somebody's grazing their goats.

People try to protect you, as a youth, especially as a black, African American youth

I started asking my sister about it, I was like, "What's with the animals?" And she would tell me stories. I think then she was teaching second grade, and kids in her class would buy milk from the cow next door. So it's just so weird, given whatever Compton's supposed to be. It’s just a small area of the city that's zoned for agriculture, it's not like people have farms. It's an area where are these huge houses, these really big beautiful houses. But you drive through these neighbourhoods, and there's 150 chickens in the middle of the street. And you've got to wade through the chickens.

There's an African American woman there who has an equestrian school. It's weird because in LA no one knows about this. It's just, it's so strange... And the Mexican Americans mostly have brought their own traditions from Mexico about agriculture, about horse culture, so now that's changed. So now there's a rodeo. It was really hard in the book to fictionalise and make it absurd and real, all at the same time. To make it believable and absurd at the same time, based on something that's sort of true.

The protagonist is technically unnamed, although he has a pet name, Bon Bon, but you don't officially name him, except to say that his surname is Me. Which was once upon a time Mee, and has been shortened by his father to Me. So his name's Me, which suggests he's some sort of everyman figure or whatever, but he also clearly sees himself as something of an outsider, so what's going on there?

It's pretty simple. In the States you have these Supreme Court cases, like Roe versus Wade or Brown versus the Board of Education, or Dred Scott versus the United States of America. So I just loved the idea of Me versus the United States of America. So I came up with what’s hopefully a funny story, just so I can use that line.

I want to talk about Me’s father in the book. You just mentioned about going to see polo matches, and I've read that your mother was really into martial arts, and bought that into the house. Is there something of your mother in the father character, in the way that he raises Me?

Oh yeah, no doubt. My mom, she's incredibly smart and her mind is huge. So you were talking about martial arts. My mom was into karate, ever since she was 14. She grew up in Brooklyn, and this eastern religion bookstore somewhere outside of Bed Stuy just changed her life. So she's a huge Asianphile. She's been to China, we've both gone to Japan, we love sumo wrestling. I grew up watching sumo wrestling with my mom on TV. My mom broke a brick when she was 50. There was a second there where she tried to raise me and my sisters as Japanese.

My mom's special. And she speaks Japanese, she can do calligraphy. For a long time the Crenshaw District of LA used to be black and Japanese-American. And there was a beautiful theatre there that used to show old Japanese movies, so from when we were eight, nine, 10, she would drag us every other weekend to see all these Kurosawa movies, these Mizoguchi movies.

Everybody in my family is right handed except for me and my sisters, which is a little unusual I guess, the three of us are left handed. So my mom claims that she tied our right hands behind our back and raised us for the first two or three years with our hands tied, so we would be left handed, for whatever that's supposed to do for you.

The father, he's a psychologist, and he's raising Me in some sort of wide-ranging social experiment. But more prosaically within the neighbourhood, he has another role, he's referred to as something else.

What is he referred to?

He's referred to as the nigger whisperer.

There you go.

So what do you mean by that, what does he do?

People try to protect you, as a youth, especially as a black, African American youth. And within that, there can be some restrictions. People are always, “don't do this, do that, wear a sweater”. And I have a friend, her dad is a psychologist, and we talk about how her father raised her. And he was trying to raise a bulletproof child, in a weird way.

But that also has an effect. It's all well intentioned, but he's like, "man, there's so much out there, there's so much danger, for this young black woman." And he's supplying the knowledge that he knows.

I have a background in psychology. The whole book is exploring how do you put all this stuff in like a contemporary setting, all these classic psych experiments that I grew up going "man that's crazy, I can't believe they did that." That's the type of thing this father would do to his son in the book. It's masochistic. Some people believe that the way African Americans raise their kids goes back to slavery. There's so much legacy, and this for me is a little bit of a nod to that but with a little more of a social-scientific bent to it.

But then particularly the nigger whisperer aspect is that he goes out and talks down suicides.

Yeah, he's the community therapist you know. Horse whisperer. It all ties together to the faux-agrarian, the urban, and how do I meld all these worlds together.

As much as it's a novel about race, it's also about class. The father sets up the Dum Dum Donut Intellectuals, a group of intellectual black men who come and meet in a doughnut stall and talk. This one guy emerges out of that as a sort of competitor, and then becomes Me's antagonist. So who's he, where does that guy come from?

There's a certain talk show host in the States who… Not all people obviously, but some people of a certain class, of a certain background, of a certain way of how they see the world, have a hard time laughing at themselves.

I’m going to tell a weird story, sorry if like I'm rambling. I was in college once, something happened, two black guys did something, I can't remember what. And there was a guy, and he went, "Oh no, I can't believe they're doing this.” I was like, "Why are you so upset?"

He goes: "This is so embarrassing."

A white person does this and it's just him fucking up, then a black person does this and it's we're all fucking up

I was like, "How can you let them embarrass you?” And this was the first time I saw that thing of, a white person does this and it's just him fucking up, then a black person does this and it's we're all fucking up.

I just had never thought about it before, and I said: "That's ridiculous man, that has nothing to do with you. That's not your problem." I mean, it is his problem, he’s got to deal with it. But it's so hard to live everybody's life, that's what I'm trying to say. It's so hard, and I can't do it. I've actually never done it.

I grew up thinking a little different because my mom never talked about race when we were little. She talks about it all the time now, but me and my sisters, we had to figure out so much on our own. Because we grew up in white Santa Monica, not rich or anything. Then we moved to these different, changing neighbourhoods and we just had to figure it out.

And so again in college, this is the first time like I had been around black kids in a long time, when I went back to school, because I ended up going to all white high schools. And so the kids would look at me and go, "Where are you from? Who are you?" all the time.

I think part of it is just being in California and there's a different kind of multiracial thing in California. I had a friend ask me to do a blurb R Zamora Linmark, a Filipino guy, he's got a beautiful book called Rolling the R’s, about this funny gay guy. It's hilarious. He asked me to write a blurb for it, and I'm thinking about this book which I love, and it brings me back to being in LA, and I had Filipino friends, and in my head I used to think that Filipino and black kids were alike.

We liked ketchup, we liked basketball, we liked fried foods. But there was a weird bond. But it's just a different way I thought about race and all these things, who my friends were. I'm not answering your question, I'm sorry.

I've just described this book as a book about race, and I've seen you write elsewhere or talk elsewhere that actually all books are about race, all books just don't realise it.

I used to have a poetry class, I got my MFA writing poetry, and one day Alan Ginsberg was absent and his class was covered by this beat poet named Gregory Corso, maybe some of you guys have heard of, who was sort of famous in the beat culture.

A few of us were trying to write different things. A woman read a poem, and he said, "you don't get it – you're supposed to be universal." And I said, "how can you say that?" It was so good for me to hear that because I was just like, OK, this is what I'm up against in a weird way. The word now is normative. And as I've got older, writers will occasionally meet me and they'll say – sorry I'm not trying to brag or anything, but they'll say, “I was so happy to read you, because you just were yourself." And it's so weird for me that people had to actually make that jump.

But it’s something that I kind of did. For example I read all this literature, there's no humour. Me and my friends talk about all the same stuff, but there's a lot of humour in there, there's a lot of humanity, it's not just rhetoric, rhetoric, rhetoric, rhetoric. And that's just something I thought was missing in a lot of literature, not just African American literature necessarily.

I was best friend with this family called the Keatons. And they had gone to these Muslim schools although they lived in these white suburbs. Miss Keaton, she would kill me if she heard me say this, but she used to talk so much crap, black power this, black power this, and she had this beautiful little poster in her thing, it said: “Black Ball, Black Male, Black blah blah blah,” and at the bottom it said “White Lies”. And that was clever. But then one day, some white people came over and she took it away and hid it. And I was like, "Oh, okay, this is how it works". But you just learn the contradictions and the hypocrisies. It's not right or wrong or anything.

I want to talk about Hominy Jenkins, the character that becomes Me's slave. Unwillingly, Me does not want a slave, it's sort of forced upon him. He was also the understudy of the character Buckwheat in The Little Rascals. The audience might not know who the Little Rascals were, so tell us who Homity is and something about that, the real world version.

There used to be a show, me and my friends all grew up watching, me and my sister still talk about it to this day, called the Little Rascals. It started silent in the 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, even into the early 1950s.

It was a little racist show on television. But within that was how talented especially the black kids were. You see how gifted, how smart these kids are, but they're just the butt of every joke. But they're the fulcrum of everything. When you're young, you're not quite sure how to process that.

Some people believe that the way African Americans raise their kids goes back to slavery

And then, do you know who Amiri Baraka is? He's a poet, beat poet, black arts movement poet, from the 1960s, 1970s, but a brilliant, brilliant cat, and I would occasionally go hear him read. And one time he talked about this American film star, who was called Stepin Fetchit, who was the quintessential coon. I mean, the portrayal of coon didn't get any more racist really. Stepin Fetchit moved all slow, he spoke really mealy mouth, you could barely understand. And Amiri Baracka started talking about Stepin Fetchit as a revolutionary.

And I was like, "Wait, what!?" And he goes, "Only the real sellout motherfucker, when the master tells him go fetch that, runs.” I was like, "damn!" There were these moments of how do you process this stuff. What's really being said? What's underneath that?

So anyways, with the Little Rascals which I love, despite whatever it is, there was a dude in line, because there was always a black guy. There was like Sammy Sunshine, then Farina, then Stymie, then Buckwheat. And then I was like, who was Buckwheat's understudy? Who was next in line, where was that dude when something happened? And that always cracked me up, so I was like, yeah, I wanna bring this character to life somehow.

What you describe there, which is what you describe as coonery, which is that sort of playing of stereotypes for comedy effect, for a white audience. We'd like to think that sort of thing of the past.

It's not, it's not, it's not.

So where do we see that in popular culture?

I think you see it all the time, and I don't think it's necessarily a bad thing. There are times when I go oh, I can't believe so-and-so did that. But it's just interesting to me how these things continue to manifest themselves. The same bug-eyed smile. The same things to disarm.

I'm not saying that Obama's a coon. But it's interesting, his first public thing, he made the joke that so many black men make when they're in an all-white environment. It's his first press conference, and he made this joke about “oh, here's my tan”. And I just went, “I can't believe he did that”. He said something about him being a mutt also.

But it was to go, "hey! I'm okay, I'm okay." And I knew what he was doing. And it's not the same thing, but it's that body language is the same. And that raspy voice.

There's those little cues. For women there's that high pitched Butterfly McQueen thing, it just like – part of it is how do you set yourself apart, how do you? For me, a lot of that stuff has not changed. It has not changed.

Why does Hominy want to be a slave?

Oh just because it's the role he's comfortable in, it's how he gets attention, it's kind of he's been bred to be servile in a certain sense. Even though he's not fundamentally, but he's used to it. That's how he shows appreciation, you know.

In my first book I had a character who was a dancer in the 17th century. He's a free black man, and he sees the slaves picking cotton, but he loves the movement, because it's like dance to him. So he runs away into slavery cos he wants to learn how to do that. And it's a little bit of that with Hominy. I just love the idea of a slave who liked getting beat, who has a masochistic tendency.

And I was like, how does that work? I mean, there's also a power in that. Maybe not a real power, but there's a little thing of “you can't hurt me” in that. I'm not sure if it's true or not, but I liked exploring. That's all I'm saying.

We won't give it away, but how does that manifest itself?

During slavery a lot of the time the people doing the beating were black. They had no choice, but still that's what's happening. And there's an anger, there's a resentment in that. I don't know if this is true but I was getting my doctorate in psych before I started writing, and in class one day we were talking about similar themed things and the guys mentioned something about how Gandhi used to beat his wife.

We were talking about the civil rights movement and all the violence that they suffered. And that violence just doesn't stay there, it gets out somehow.

I could see similar kinds of behaviour in my friends. I know this happened to him in his past, and he's kind of acting out in relation to this stuff. This stuff doesn't just sit there.

So we've talked about Dickens, the town, and it's been wiped off the map by the greater Los Angeles authorities, and Me has this plan basically to put it back, he puts a white line around the area to designate it, and eventually this leads to first of all the slavery of Hominy, but also the segregation starts, of a school in the first instance.

A school that's all black and Latino, so can't actually technically be segregated. So they do it by making up a fake white academy that's over the road. This has the effect of making the black and Latino school better.

Was it interesting to play around with the idea that segregation might actually have some tangible benefits?

Yeah. I was playing with that idea because I think occasionally you'll hear people say, “Oh, we were better off under segregation.” There would be a phrase if a black guy or a white guy had a store, and they were both selling ice, black people would buy the white person's ice, because “Mr Charlie's ice is colder”.

There's also a thing that some people have, about, the white man's looking on you, you're going to behave, you're going to act right, you're doing all this. I just wanted to play with these really racist, these real shallow notions – and also acknowledge the fact that even though we use these words, segregation, as artefacts of the past, it's still present.

And so for me it was really interesting to try, how do I render these thematically in a contemporary context.

I wanted to talk about the humour. We go and see a film like 12 Years A Slave, and it's very serious and it's very violent, and it puts you off your popcorn, and you come out of it under no illusion that slavery was a very, very, very, bad thing, because you've been repeatedly told that. And this book, which is also about extremely serious subjects, is incredibly funny.

And I just wanted to say, I'm so pleased that it's been shortlisted for the Booker. I don't know if it's just here or it's in the States as well, but there's this idea that funny and serious can't coexist, which I think is bullshit. But, do you prefer to approach subjects with humour?

It's just how I write. I just write. I'm not trying to write a satire, it's just how I write, it's how I see the world and how I best express myself. I guess a lot of times it is funny. Sometimes I read this book and I guess it is kind of funny, and sometimes I don't find it funny at all. It depends on the mood I'm in, it depends who's in the audience, sometimes.

OK, you wrote it so you're not going to, because you've also read it and written it and revised it and revised it and revised it, but I'll happily sit here and say this book is laugh out loud funny, every other page. It's absolutely wonderful, buy it everybody.

And again, you're sort of downplaying it, but comic writing, we'll talk about that in a sec, because I know you don't like to be described as a comic writer, but it's hard. Not only have you got to write well, but you've got to make the jokes work on the page as well. Tell us about that writing process.

For me, it's not like I’m trying to make the jokes work. It's trying to make the language work, trying to make the sentences work. I'm not a comedian or anything. So, if the language is right, then everything is right. The thing I had to learn is that some people just see the joke – some people also see the insight of the joke.

I had a friend come up to me along time ago, and she said, "It must suck to be you, because people are only going to get half of all the stuff that's in your work. They're going to read that and maybe laugh but not understand why.” Sometimes there are little words that reflect back, things that only certain people are going to know. So there's a layering there also, and that's the part for me that I'm trying to do. It's not like just the joke. But sometimes it is just a joke.

Can we just talk about your influences. I was reading this and thinking of Joseph Heller and Catch 22, the tone of it and the relentlessness of it reminded me of that. But you particularly mentioned, Richard Pryor and other influences like that, but you mention in the acknowledgements an essay by William E Cross, what's that?

I was saying earlier I have a background in psych and there used to be a journal, I think it was just called Black Psychology. I was having a hard time. Then when I came across this journal and some of his work, and he was trying to chart the progression of black identity. In psych there's a concept of being self actualised, where you're the best person you can possibly be. And he was trying to do that with blackness.

And it's interesting what a self actualised black person was to Cross. It was definitely a male. He had an idea of what you want to be. I didn't agree with it all, but I loved the care that he took and how smart it was. I can't tell you how good it was. I xeroxed it and made a big poster out of it and just put it on my wall when I was in grad school.

It wasn't until I started writing the book, because I was going to frame it around how he had these steps to blackness. But then as I was researching the book and read his work, it was interesting to see how he was changing, so his quintessential blackness thing had shifted over time as he grew. It's a thing that I learned in psych, mostly about politics, that people are always in different places. You're always growing, you're always learning, you're always saying, “yeah I used to be like this, but now I'm right here and I'm chill, I'm happy.”

And there's a beautiful movie, A Soldier's Story, by Charles Fuller, it was originally a play. I'm very familiar with how black people are always judging, “you're not black, you ain't black,” this whole thing. And this movie just talks about this in the context of World War 2 and the army and people are just so quick to judge.

There was a book – it was called like the Directory of Uncle Toms, or something like this. And it would say, here's Colin Powell, this is why this person's an Uncle Tom, because he did this in Vietnam, he did this, he let the Mỹ Lai massacre happen, he did this. And it’s like a phone book. But you flip through it and every black person you ever heard of is in the book. I don’t even know if this person knows how beautiful this book is.

And when Obama got elected, even before he served, Ralph Nader already was calling him an Uncle Tom. And I was like, “dude, what?” I love Ralph Nader and it hurt me when he did that. And just to use that phrase and not understand what that means, what you're actually accusing that person of. He's not Uncle Tom because he's selling you out, there's a whole other thing that you don't even get and you don't even appreciate.

Towards the end of the book, you talk about the idea of unmitigated blackness and you give a list of famous black artists that includes such famous black artists as Jean-Luc Godard and Bjork, and the famous French racist writer Celine, so what do you mean by unmitigated blackness?

Well in that context – I mean, it's just a book, it's fiction, it's not shit that I necessarily believe. It's just shit that I'm thinking about.

But in that context, it means by people who don't give a fuck, who are just free to be who they are. And sometimes it might not mean that I like them. And these things are things that I like and a lot of times I like things that I'm not supposed to like, because this person doesn't like me.

My girlfriend talks about her favourite Rolling Stones song is Under my Thumb. That's a vile, mean song. It's cruel. It's unbelievable. But for her, she says it's worth it, there's something undeniable in that song for her. I don't mean she supports that kind of behaviour. But we have these weird contradictions that we don’t know how to deal with necessarily

A while ago, back in the States there was this controversy of all this hip hop music with all this denigrating language for females in it. And, yeah, I can understand no one wants to hear all this all day, absolutely.

But while all this was going on, people were trying to boycott the music, I read this thing where Alicia Keys was saying, “oh yeah, I understand that, but you know what my favourite Biggie Smalls song is? Me and my bitch.” Because it spoke to some kind of dynamic which she was extremely appreciative of.

And I'm just trying to say there's no solid line, these lines shift for me, for somebody else.

Lionel Shriver has come up with this stupid ass essay "I hope the concept of cultural appropriation is a passing fad". And I agree with the premise, I do think that people should write about everything. But for her, I don't know, it might have been the headline, but it was something about, somebody calls you racist, or something, then they're censoring you. And they're not fucking censoring you. You just don't want to hear it.

And that I have a deep problem with, because people have absolutely a right to come back at you. You can't tell somebody not to be offended.

Just that narrow minded – like cultural appropriation that, only white people can do this. I was like, no, you want to make your case, you show some black people appropriating other cultures, because I do that all the time, everybody does it. You know, there's no ownership here. I don't believe. That's how it works, you put it out in the world. You put it out there to be shared, and it gets shared, it doesn't necessarily get shared the way you want it to. And it’s a risk.

And it's not fair, because someone else is going to do it and not be as good as you at it, but they're going to make 10 times the money you're ever going to make, doing your thing. That happens sometimes. And that’s the part you've got to change.