Return to Hangover Square

Revisiting Patrick Hamilton's 20th century classic

I know that I have done wrong, but I am not well. I do not really know what I am doing. I thought I was right, but now I am wrong about Maidenhead, I may be wrong. Please remember my cat.

Yours faithfully

GEORGE HARVEY BONE

The spectacular, miserable denouement of Patrick Hamilton’s novel Hangover Square, reissued on its 75th anniversary, plays out against the backdrop of the very commencement of World War II – the moment when Neville Chamberlain informed the nation that “this country is at war with Germany.” The threat of violence permeates the book like smog.

The action in what is probably Hamilton's best known book takes place between Christmas and the outbreak of war. George Harvey Bone makes a pitiful protagonist. A sad, heavy, dull man, completely lacking in self-confidence, equal parts grateful and resentful of whatever small scrap of companionship he is offered. He is at least self-conscious enough to know this is unattractive, but unable to lift himself out of this attitude.

Bone, like his creator Hamilton, is an unhappy drinker. Moreover, he is mentally ill, prone to dark, detached moods that Hamilton ascribes to schizophrenia, but might now be viewed as depersonalisation disorder. These spells get worse as the book develops, until there is no real distinction between “well” and “unwell” Bone.

All the while, Britain is attempting to convince itself that war can be put off, or at least postponed. The country itself is attempting to escape reality.

In Hamilton’s telling (or in that of George Harvey Bone, the book’s protagonist), only Nazi sympathisers really believed the Chamberlain’s claim, on his return from Munich in September 1938, of “peace in our time”. Bone suspects his Earl’s Court drinking cronies Netta and Peter of sympathising with Hitler, a not unlikely conclusion, given that “Peter, of course, was a fascist, or had been at one time – used to go about Chelsea in a uniform.”

Bone on the other hand knows that “Munich was a phoney business. Fine for an Earl’s Court binge, but a phoney business, however much you talked.”

Peter's fascism is emphasised by the fact that he once killed a man in a motor accident – a recurring theme for Hamilton, who was maimed in a car crash in 1932.

Netta may not have gone about Chelsea in a uniform, but nonetheless, she is callous and insincere: a problem because Bone, his mental fragility exacerbated by the near-constant drinking that takes up his days, is madly in love with her, or at least in obsessive lust.

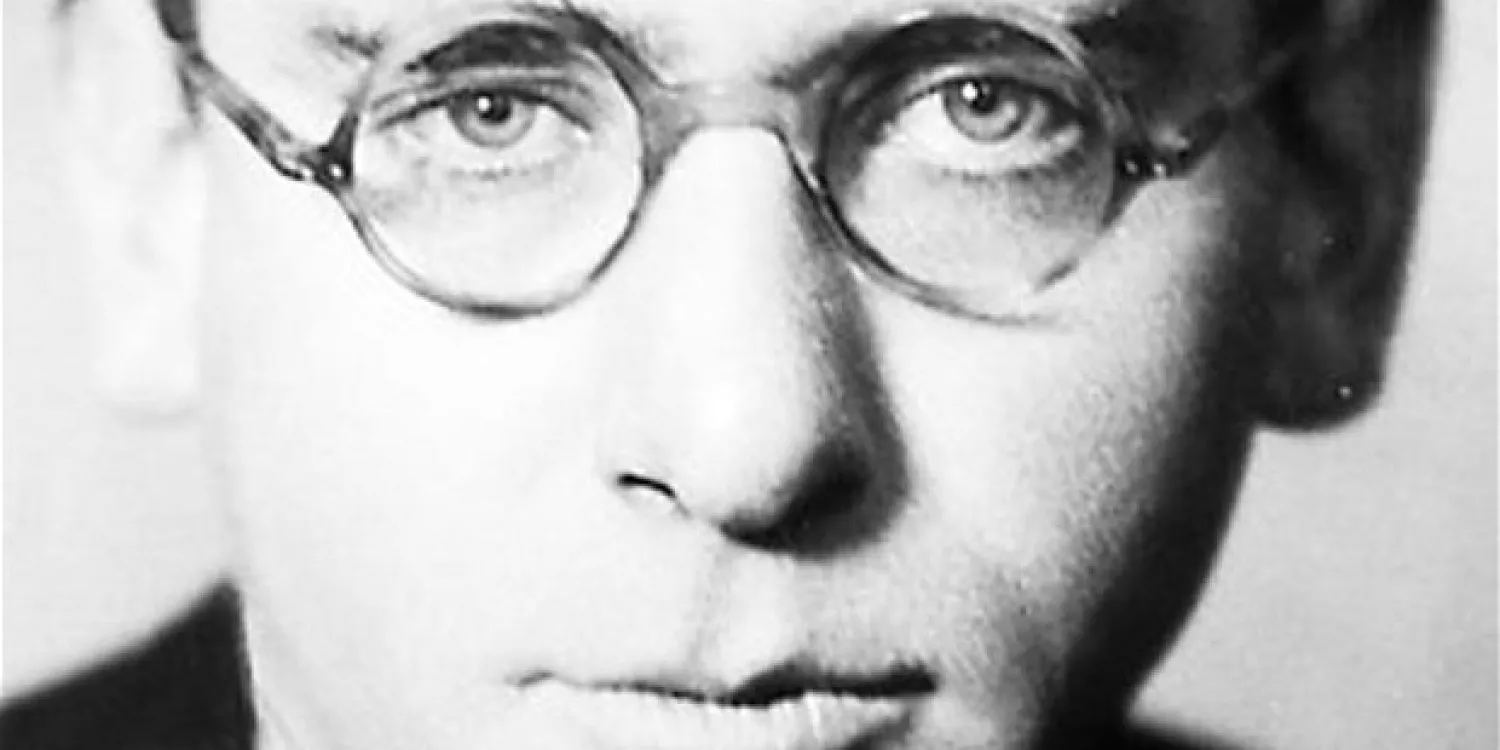

This detail, again, is autobiographical. Hamilton, despite being married, had, in modern terms, been actress Geraldine Fitzgerald’s stalker: turning up outside her house, calling at odd hours and the like, in a way that at very least would result in a restraining order today.

Bone’s alcohol intake is not so much the punctuation of life as its entire language.

And then there’s the drinking. In the tense days of 1939, Hamilton’s drinking had gone from what his friend Claud Cockburn termed “quite normal heavy drinking” to straightforward alcoholism – pints of beer topped up with spirits being the preferred route to oblivion. His devoted brother Bruce fretted, on reading Hangover Square: “[T]his novel was saturated, almost drowned in drink...What sort of life, I asked myself must my brother not now be living to be impelled to explore, with such awful percipience, every shade, every nuance, every degree in the process of getting intoxicated and sobering up?”

Actress Geraldine Fitzgerald, inspiration for Hangover Square's Netta Longdon

'To those whom God has forsaken, is first given a gas fire in Earl's Court'

Bone’s alcohol intake is not so much the punctuation of life as its entire language.The Earl’s Court crew exist to drink: they meet in Netta’s flat to drink before they go drinking. Every day begins with a discussion of how drunk they were the night before and where they will drink today. Bruce Hamilton was right to worry about his brother’s ease in describing these patterns.

Bone, poor, weak, self-pitying Bone, naturally blames Netta for his miserable drunken state. Fortunately, he has a solution. Or rather he has two solutions.

Bone number one will somehow convince Netta to love him, and then they will live in simple rural bliss on the Sussex Downs.

Bone number two, the Bone that manifests in what his drinking companions call his dumb, “stooge” moods, will kill Netta, and then escape to Maidenhead (about 25 miles west of London), where he will float along the Thames and be at peace.

Hamilton’s presentation of mental illness as a sort of on-off switch (“Click!”) may be simplistic, but the description of the confusion, fear and loss of control Bone goes through are genuinely sympathetic and moving.

Bone is trapped by his undiagnosed mental illness and his alcoholism, and he binds all this up in his devotion to and abhorrence of Netta. She embodies everything that’s wrong with the world for Bone (and Hamilton). She is thrilled by the brutality of fascism. She is vacuous, self-absorbed, unable to think of anything beyond her own immediate desires: drink, amusement, sex (with, it seems to Bone, everyone but him).

But is she really so bad? One could put her characterisation down to Hamilton’s misogyny, but then he is perfectly capable of creating sympathetic, believable women. Jenny and Ella, the prostitute and barmaid in Twenty Thousand Streets Under The Sky, for example, are both bright women who are condemned to drudgery and disappointment in a man’s world — Jenny, in particular, is punished for abandoning her expected role in life (domestic service, marriage), for just one night of fun that goes wrong. Miss Roache, the heroine of The Slaves of Solitude, written after Hangover Square, is pretty much the only likeable character in the book, condemned to boredom in the war-time Home Counties, with even her one outlet, her publishing job, taken from her due to war shortages,

As Twenty Thousand Streets also shows, Hamilton is capable of portraying a fool in love with a girl who doesn’t love him back, without implying that the girl is in the wrong.

So Netta is as bad as she is drawn: is she, in fact, fascism (with actual Blackshirt Peter merely added for emphasis)? Is Hangover Square an explicitly political book, rather than one that takes place against a background of politics?

Oh my darling Party Line

By the time he was writing Hangover Square, Hamilton was an avowed Stalinist, if a little light on theory. He told his brother “I have no doubt the Trotskyists [sic] are the sods nowadays – replacing even the [Ramsay] Macdonalds in filthy humbug and invidiousness.”

One could, if one wished to, suggest that Bone’s “schizophrenia” is a response to the Hitler-Stalin pact. In this telling, Netta in fact represents not fascism, but Moscow: demanding ever-greater loyalty from admirers while sending ever more confusing signals.

His biographer Nigel Jones suggests that Hamilton may have been “too frivolous to be a good Communist.” Perhaps this is true: he did call his pet parrot “Pollitt”, after the British Communist leader of the time Nonetheless, Hamilton adhered strictly to the party line, spurred on by Cockburn, a keen propagandist for Moscow. And while he may have been confused by the Hitler-Stalin pact, it did not deter him. HIs avowed communism outlived Stalin himself, and he attempted to love Khrushchev as he had Uncle Joe.

But more than plain politics, there is a fear of the modern world inherent in Hangover Square – a modern world represented by the war. In common with Orwell's Bowling in Coming Up For Air, Bone yearns for a Georgian vision of England that no longer exists. Bone eventually arrives at Maidenhead to find that it was “no good at all”: "It was just a town with shops, and newsagents, and pubs and cinemas. It wasn't, and never could be, the peace, Ellen, the river, the quiet glass of beer, the white flannels, the ripples of the water reflected quaveringly on the side of the boat, the tea in the basket, the gramophone, the dank smell at evening, the red sunset, sleep..."

This England cannot be regained: the next war is a mere continuation of the last one, a final nail in the coffin of a world of which the likes of Hamilton and Orwell were the last generation.

Poor, sad, schizophrenic George Harvey Bone himself represents the confused, sad state of England in 1939: merely waiting for one nightmare to end and another to begin.