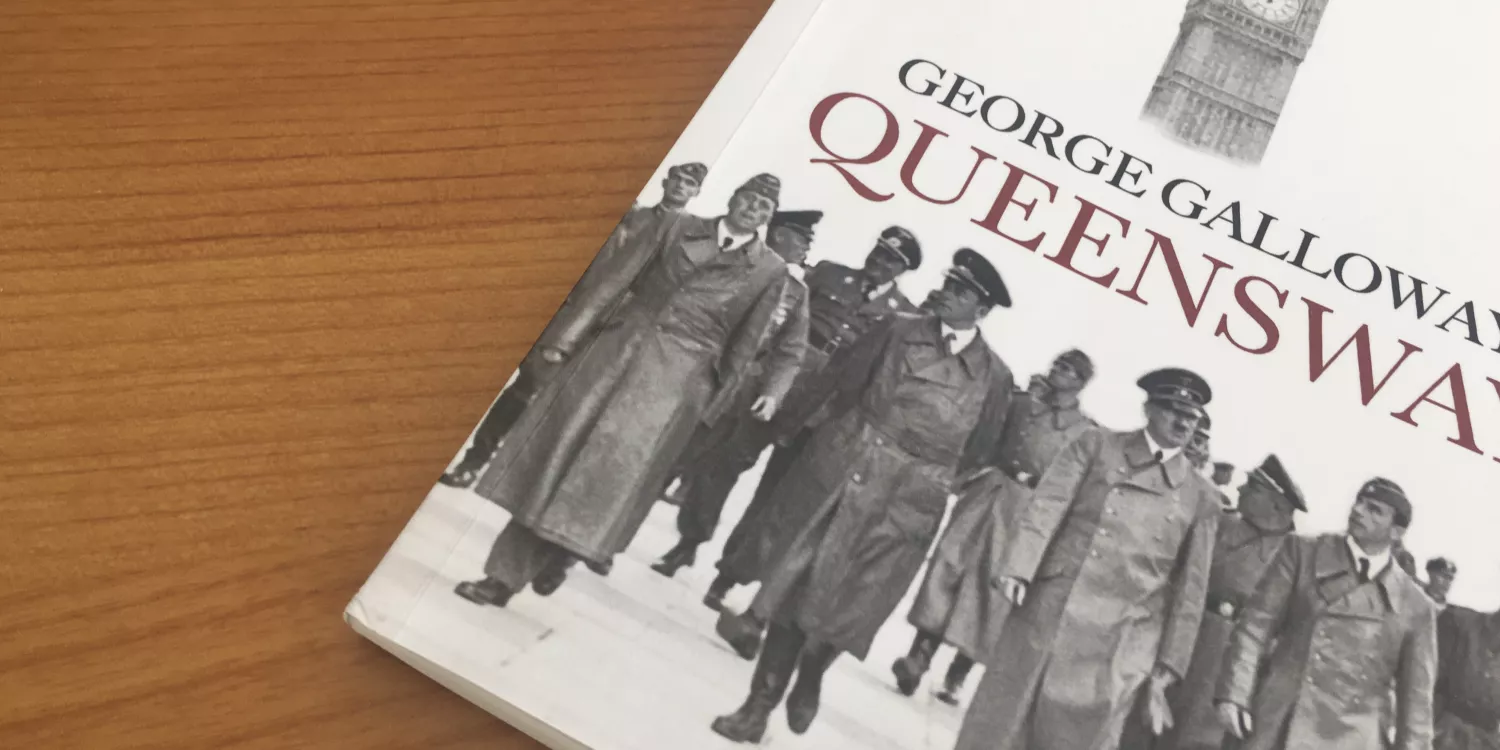

Review: George Galloway’s Queensway

It’s a novel. By George Galloway. What did you expect?

First things first: an apology. I wish to say sorry to George Galloway, former MP for Glasgow Hillhead, Glasgow Kelvin, Bethnal Green and Bow, former leader of the RESPECT party, and current leader of the Workers Party of Great Britain, for making jokes about his hat.

On at least one occasion I have made jokes about Galloway’s tendency to wear a hat indoors, a wide brimmed fedora that places him somewhere between Marlon Brando’s Sky Masterson and Robert Mitchum’s Reverend Harry Powell.

It’s a strong look and one, it turns out, not motivated by sheer vanity. I recently discovered, while watching George chat with his friend Steve Topple online (I live a very full life), that Galloway claims he wears the hat to cover the scars he bears after he was assaulted in 2014 (by one Neil Masterson). If this is true, then frankly, the hat wearing is his business and his alone, though I would add that it’s better at least that he wears a snazzy fedora than a forlorn baseball cap. So, chapeau, George.

I mention this in order to assure George that I approached his new, short novel Queensway, in good faith. (As Dorothy Parker wrote in her review of Mussolini’s The Cardinal’s Mistress, I would strip a gear any time in an effort to be square toward that boy). I purchased Queensway directly from George, and he very kindly sent me a signed copy. I hope this indicates a detente in our relationship, a deescalation from the time he came to the door to personally bar me from a public meeting he was holding at the London Irish Centre, where he had promised explosive new information on the Salisbury poisonings (one notes that information never seemed to come to light; perhaps if he’d let this member of the press in...).

Queensway is billed as the first in a series; an alternative history thriller after the fashion of Robert Harris’s Fatherland. The Nazis have invaded Britain with comparative ease, having taken hundreds of thousands of prisoners at Dunkirk, and are now set up in London, with large parts of Britain under their terrible jackboot. Mosley is nominal PM, and Edward is back on the throne. But of course it’s the Germans who run the show, from the SS headquarters in Whiteleys department store on Queensway. Why Whiteleys? Well. “Hitler had had his eyes on Whiteleys long before he strode triumphantly down the Mall...” our narrator explains.

Whiteleys must be quite the iconic venue, you can’t help thinking, if Hitler personally chose it as the “nerve centre” of the occupation. Do tell us more, George.

“The store - once the largest shop in the world - also had a history that would appeal to [Hitler].It was originally a series of shops founded by William Whitelely along Westbourne Grove, just a short stroll away from its present location, expanding to a massive food empire employing 6,000 people, with country farmlands to supply produce. Most of the employees lived in company owned....”

And on and on. There’s a lot of this in Queensway. A person/location/concept is introduced, and then we are given what feels like a quick Wikipedia tour. When Mosley turns up we are given near enough a page-and-a-half detailing biographical background.

When one character tells another about Klaus Fuchs, the real-life atomic scientist and Soviet sympathiser, he starts by pretty much reading out Fuchs’ Wikipedia page. “Born and brought up in Germany, his father was a Lutheran pastor, he was active in the Social Democratic Party and their Paramilitary wing, but he was expelled....”

This goes on for four paragraphs. Perhaps in Galloway’s dystopian alternative world, Wikipedia was already in place by 1940. (Fans of George will know that he takes a keen interest in Wikipedia editing.)

Anyway, this is all sort of enjoyable, in its own way, like half watching a History Channel documentary while scrolling through Instagram looking at pictures of other people’s babies and sourdough loaves.

But there is a plot to follow, which, so far (remember Queensway is the first of a series), consists of this: The Nazis have arrived, and have started doing bad things to the east End’s Jewish community. The resistance is emerging as a force, led by the twin behemoths of British politics, Harry Pollitt of the Communist Party, and yer actual Winston Churchill, who has managed to escape the clutches of the Germans and is... living in a coal mine in the Welsh valleys, where he is building a friendship with his communist protector Arfon. Oddly, the Communists are leading the British resistance even while the Hitler-Stalin pact remains in place, and the party has not actually been banned in Britain.

The resistance’s totemic guerilla figure is known to the public as... Harry Kane. (I’m not making this up. Galloway is, I’m not). In reality he’s a young east end Jew called Sol. Harry/Sol’s mission as an underground guerilla is to link up with other resistance members (who are particularly strong in Edinburgh), and launch spectacular guerilla attacks on the occupiers. Meanwhile, some other communists are tasked with tracking down Fuchs before the Nazis get to him, in order to keep the secrets of the atom bomb out of the hands of the Germans (and in the hands of the Red Army, we assume).

Queensway opens (and closes for that matter), with a scene setting out two recurring themes: misogyny and pornographic violence. The very first woman we encounter, seemingly a destitute refugee offers sex to our hero. But he is too tied up in his work to accept. Moments later, his work comes to fruition when a bomb blows up a band performing for some assembled Nazis.

Galloway gets close in with the detail, sparing us neither cliche nor Partridge-ish aside: “His music stand had sliced through his neck like a knife would have cut through butter, if there had been any in these straitened times.”

Queensway at least maintains the most important element of any thriller - pace

Later, hanged victims of the Nazis are left to dangle from a bridge and “remain there until the corpses rotted and they dropped into the Thames or their bones were picked clean by scavenging birds and they played chopsticks with their beaks on the bones.” Galloway can’t resist the sardonic addendum. In oratory, perhaps, it serves him well (though I’ve never seen the appeal) but on the page it manages to be both glib and crass.

Women, meanwhile, well, it’s as you’d expect. Lips are indeed beestung, and breasts do swell. A Nazi secretary (called Helga, naturally, and going “to seed” at 40) is only good for “a bend over the desk and a few quick thrusts or mouth relief with her on her knees before him.” (Mouth relief!). There is, to be fair, a female hero of the resistance. She is “very pretty”, and her prospects as a sexual conquest are immediately scouted. We can only assume that she will get into what George might call “the sex game” in book 2. Early on, an innocent women is threatened by Nazi torturers in a manner that is lurid to the point of pornographic.

For all that, Queensay is not exactly a terrible book (you can use that for the blurb if you like George).

It at least maintains the most important element of any thriller - pace - and the plot, while ridiculous in detail (the denouement,again, I am not joking, takes place at an England v Germany football match at Wembley, with Stanley Matthews running rings around the Boche), is at least coherent in total. Even accounting for the occasional encyclopedia entry interlude, the whole thing zips along. And it’s short.

But why a novel George? And why now? One can have endless fun playing “resistance or collaborator” - imagining who, if the Nazis invaded tomorrow, would be willingly complicit and who would take to the hills with a rifle - and Galloway probably pops up in those conversations more than most modern public figures. Perhaps with Queensway, with its heroic Jewish resistance and depraved Nazis, George is signalling his own answer to that question.

And who are we to doubt the current leader of the Workers Party of Great Britain? But at the heart of Queensway lies a combination of sentimentality, vulgarity and violence that this reviewer at least can only associate with one political tendency.