From the block typefaces of 1960s futuristic posters to the neon hazes of Blade Runner, science fiction is one of the most distinctive genres out there. It’s something you instantly know when you see it. But despite being so recognisable, trying to define it can be harder than you think. Into the Unknown: A Journey through Science Fiction, a new exhibition at the Barbican in London, looks at the genre’s influence across film, literature, graphic design and contemporary art – from the machines of Jules Verne, to Afrofuturism and Charlie Brooker's Black Mirror.

The exhibition is curated by Patrick Gyger, a historian and writer who used to be a co-manager of the European Space Agency’s research programme Innovative Technologies from Science Fiction for Space Applications. The initiative scanned all forms of science fiction for innovative ideas that the European Space Agency could put into long-term development.

Assisting Patrick, is Laura Clarke, a curator who specialises in contemporary arts. Together they’ve put together a vast overview of the genre, splitting the space into four chapters. Entitled Extraordinary Voyages, the first section starts in the mid 19th-century, by examining the narratives where science fiction first took root.

When walking me through the curatorial decisions made when putting the exhibition together Laura explains: “The exhibition starts with how these ideas are postulated from early science fiction stories – even though it wasn’t called science fiction at the time.”

Despite playing a vital part in how the genre came to be so distinctive, the stories are now relics of the past and come with their own set of problems when you start to look at them in a contemporary context.

“It’s a very specific perspective that it comes with all kinds of political and social problems. For example, the idea of mapping the world and going to unchartered territories isn’t something that doesn’t sit comfortably with how we understand the world now. We wanted to emphasise the thinking at the time and to celebrate those stories as stories, and not as tools for understanding the world.”

But the exhibition is much more than a collection dedicated to a bygone era. Walking us right through to the present day, it’s more of the more contemporary works that stand out. A key part of Laura’s role was to show how science fiction is articulated in art.

“I think for a lot of people science fiction feels more relevant now than ever. And that’s not just because it’s becoming increasingly popularised through Hollywood franchises. It’s a genre that lots of people are really interested in, without necessarily thinking of it as science fiction.”

She wanted to challenge the way we define science fiction by showing how the same “considerations” have sprung up in art. When asked what she meant by considerations, Laura clarified, “I mean issues that are both pertinent and contemporary. Things like the impact of technology on humanity or our dwindling natural resources.”

A video piece by Kenyan artist Wanuri Kahiu, called Pumzi, imagines an African landscape 35 years after an apocalypse where everyone is forced to live in subterranean Nairobi communities, reusing their own sweat and bodily fluids due to a lack of water.

Exhibitions in the Barbican’s Curve space are normally contained to the confines of the gallery’s concave walls, but in this exhibition, the contemporary artworks spill out to the rest of the building. Dotted around the public areas, walkways and the rest of the arts centre are installations, sculptures and video pieces placed to make the audience think differently about how we imagine potential futures.

“Science fiction is ultimately an exploration so it’s about taking an idea and pushing it a step further or using your imagination in a different way, that still has some kind of concrete relationship to the present.”

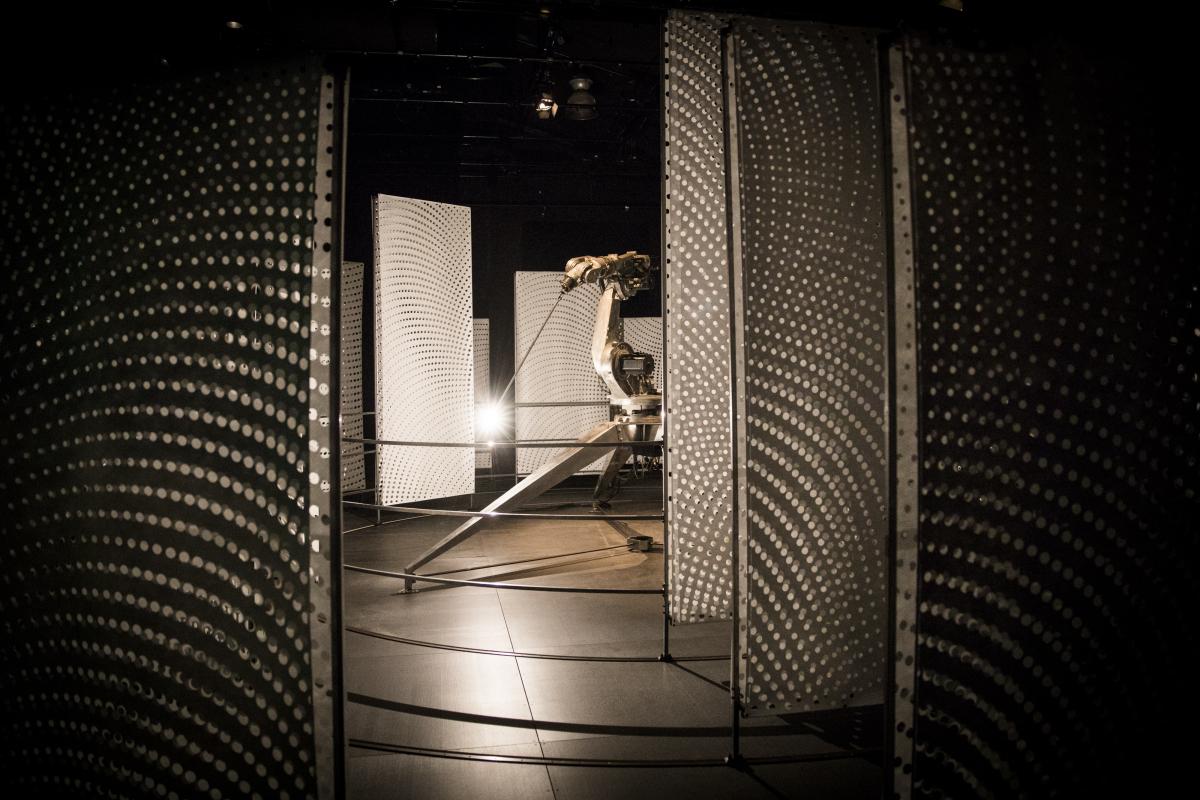

In the underbelly of the building lies the Pit Theatre. Usually reserved for theatre and dance performances it’s currently home to a new commission by Conrad Shawcross. Consisting of a fenced off robotic arm, hypnotically moving through spotlights and dividers to create an impassive ballet of steel, wires and whirring sounds, the installation brings the cold panic of Sci-Fi to life.

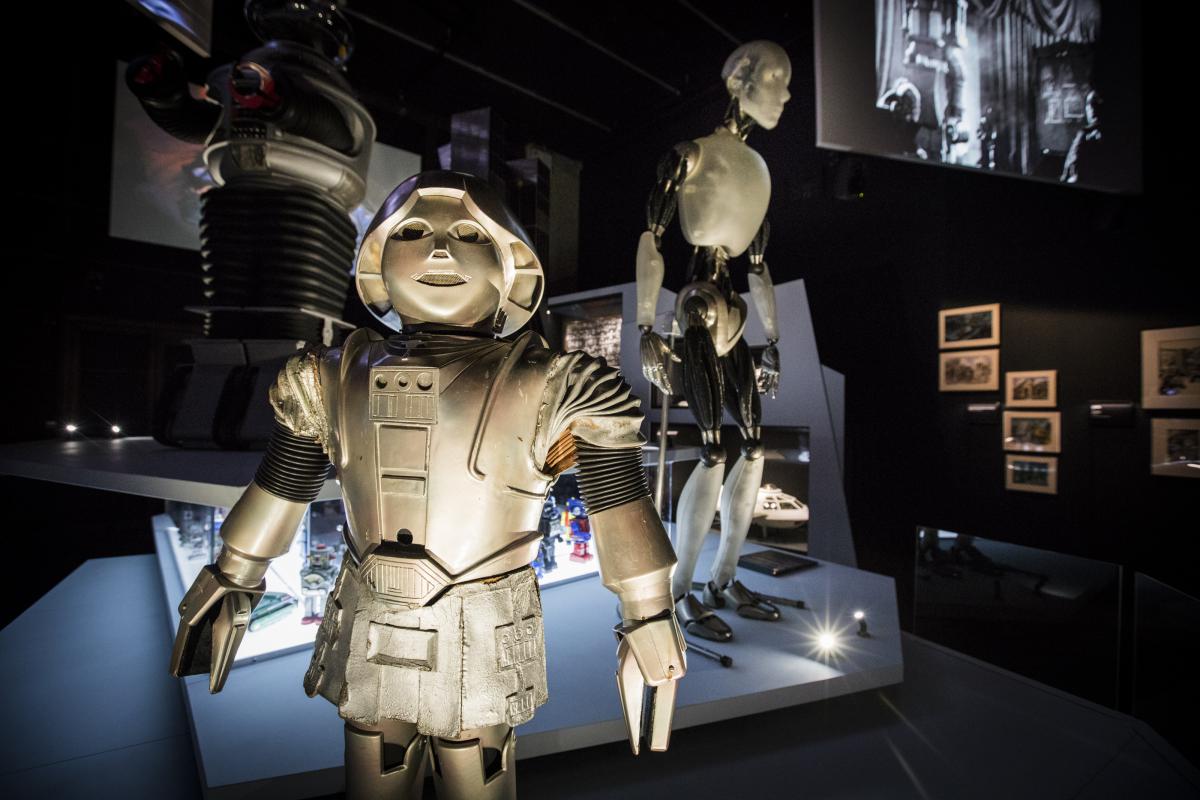

All of this is to get people living, breathing, and feeling science fiction. One of the key ways it does that is by taking moments from popular culture which brought the tropes of the genre to a wider audience and brings them to life.

After Charlie Brooker’s hit TV Black Mirror was snapped up by Netflix, the online network championed the series as an “anthology that taps into our collective unease with the modern world, with each stand-alone episode a sharp, suspenseful tale exploring themes of contemporary techno-paranoia.”

The perfect distillation of technological possibilities and imagined futures gone wrong, the curators were keen to somehow include Black Mirror in the exhibition. After approaching the creators of the series, Annabelle Jones and Brooker, they settled on an installation that brings a particular episode to life in the light box that sits in the Silk Street entrance to the gallery.

The six-channel projection cuts moment from an episode in series two called Fifteen Million Merits and splices them up, to then mash it all up together again. The end result creates the same sense of being overwhelmed that underpines the episode.

Confined to a world of hyper-artificial cubicles, in the episode people live surrounded by screens that control every aspect of their day but become overwhelmed by the constant interruption of visual noise.

Outside of the here and now, the show plays with other overlooked aspects of pop culture. Astro Blacks, a two-chapel video installation called Astro Blacks by Soda Jerk, takes moments from social politics and African American music culture and presents them as science fiction.

“It’s like a visual collage of mash ups and music,” explained Laura.” “It uses Sun Ra, the cosmic jazz musician, as the point of departure and then layers lots of references of everything from speeches by Ronald Reagan, to Public Enemy music videos and excerpts from a documentary about the Manson family.”

Astro Black: Race For Space (excerpt), 2010 from Soda_Jerk on Vimeo.

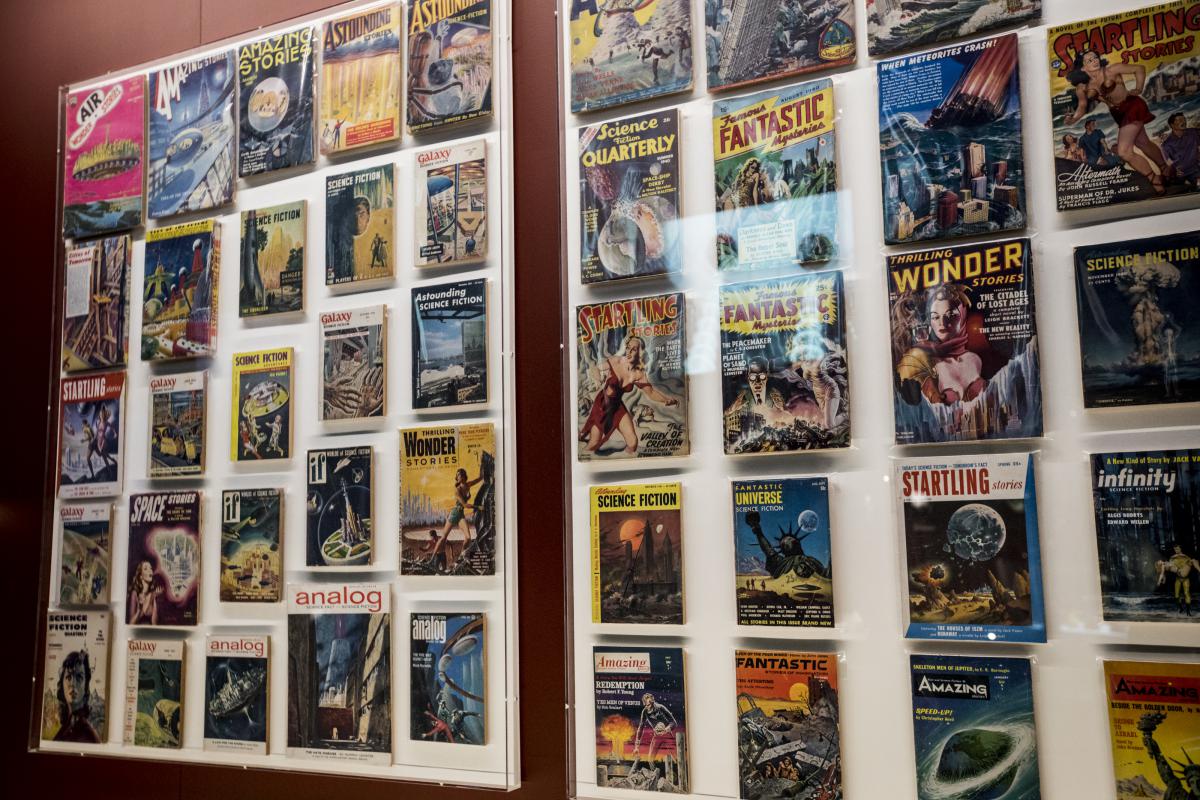

Despite the incredible variety, there is one consistency throughout the show. In the middle of each section sits a glass cabinet of books, full of first editions, such as Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe and Thomas More's Utopia, aimed at highlighting the original tales of arid landscapes, journeys foreign planets and technology gone array. Anchoring the various strands back to as a reminder where it all came from:

“The genesis of all science fiction that we know today, comes from the literature that pushed technology beyond what was in existence at the time.”

In essence, as much as the genre gazes towards to future, it’s equally important to look at the past in order to understand just how we got here.

Into the Unknown is on until 1 September 2017