If the 20th century taught us one thing about aesthetics, it is that authoritarians do not do architecture well. Encumbered by urgency, where history is something that requires construction, autocratic regimes continually show they lack the eye of their dynastic forebears, and majesty soon gives way to megalomania.

For all of the gains from the collapse of the Soviet Union, it is often forgotten that its end gave birth to five republics in Central Asia, each with their own strongman, and each with their own need to make history. In 1996, Nursultan Nazarbayev, president of newly-independent Kazakhstan, decided a small provincial town called Akmola in the north of the western-Europe sized-country would become the new capital, replacing the established capital Almaty in the far south. It would be renamed Astana, meaning “the capital” in Kazakh.

Gold towers and city wall building

Some believe Nazarbayev was spooked by a secessionist movement in the north, where elements of the Russian-majority population were stirred by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s 1990 essay Rebuilding Russia, where he proposed cutting other ethnicities loose and creating three states for ethnic Russians. The official line was that Almaty is too prone to earthquakes and wasn’t fit for further expansion. Either way, Astana was rapidly developed into a biznes hub for the burgeoning oil and gas industries. Colloquially referred to as “the Dubai of the steppe”, it is perhaps now best known for its outlandish architecture.

Driving from the airport south of Astana, a bright purple glass building housing a Kazpost branch winks at me in the morning sun as the dull shrubbery lining Kabanbay Batyr suddenly gives way to a high rise city. On the other side of the road, two gold towers housing Kazakhstan’s sovereign wealth fund and other government business ventures dominate the gold-windowed, curving House of Ministries, in a construction that looks like an ostentatious version of a city wall. With building exteriors almost exclusively fashioned from chrome mirrorballs, it is as though a team of budgies was given architectural licence to override the flat, grid city.

Bayterek monument

The golden egg of the Bayterek monument bursts through the centre of the Astana’s south bank, and if you take the elevator up for a view of the city from the air, you can put you hand in Nazarbayev's impressive handprint as you look down to his presidential palace. Nearby, a turquoise office tower expands out at the top, like the pages of a fanned book. Further south, a different shade of turquoise adorns the Astana State Auditorium, looking more like a submerged luxury boat than the petals of a flower it is said to represent.

The buildings, constructed with a fixed purpose in mind, are imposed on the landscape. Nature is at best a distraction; the Ishim River that cuts diagonally across the city is largely ignored as an obvious centrepiece. Parks are finely curated geometric spaces, lifeless but for teams of workers plucking weeds on hands and knees in the shadow of a bored supervisor. Ubiquitous dandelions provide sport for the wind, with balls of dandelion pollen tumbling down the streets, and into nasal cavities, with the slightest gust.

Bayterek monument

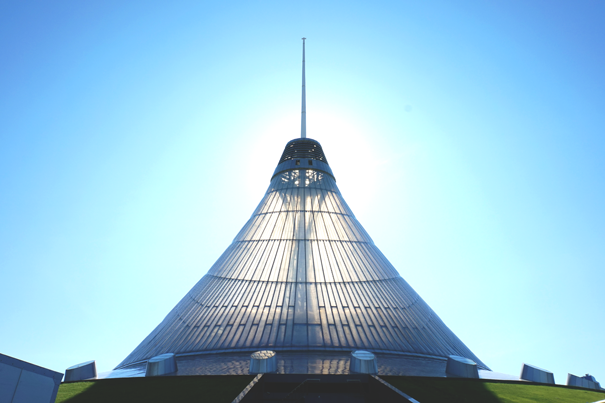

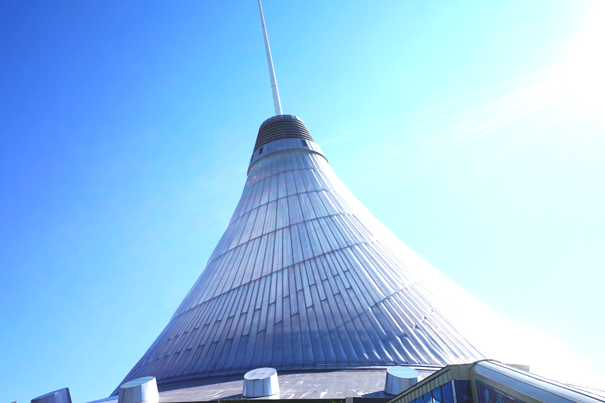

Like the Hoxha and Kim dynasties, Nazarbayev seems to have the dictatorial penchant for outlandish pyramids as capital centrepieces. Astana’s south bank, the epicentre of its design, is bookended by pyramids, albeit ones this state has seemingly been able afford, even if they were designed by venerable British architect Norman Foster. The east is home to the the Palace of Peace and Accord, a blue-tipped white pyramid atop a hill, which hosts a triannual tete-a-tete of the world’s major religions and allows a fantastic panoramic view back on the the city. The west of Astana’s south bank features the Khan Shatyr, a sloping, plastic pyramid that glows in the sun and houses an entertainment complex that includes dinosaur and water parks, and every international retail brand imaginable.

Palace of Peace and Accord

Such buildings are part of a wider trend in the region: the last two decades have seen the emergence of a common architecture in petrostates: cosmopolitan, gaudy designs that are completely removed from the culture of their home. This style has probably stemmed from the rapid rise of Dubai, with its irregular but spectacular skyline, and extended across the region. Saudi Arabia has taken to bulldozing significant religious monuments on the basis of ‘idolatry’ and replacing them with shiny shopping malls and hotels. Putin and his boy in Chechnya, Razman Kadyrov, have reconstructed the war-torn capital Grozny into a business hub that looks akin to an open-air strip club. Gas-rich Turkmenistan has created over 500 buildings made of white marble in the capital Ashgabat, with President Berdymukhammedov even awarded the title of "Distinguished Architect of Turkmenistan" by his parliament.

Petrostate architecture is unambiguous – the buildings themselves could be smoking cigars and throwing $100 bills into the air. The aesthetic represents the disconnection from any shared cultural heritage with its citizens, not to mention material disenfranchisement, that is necessary in order to enable elites to use the state's natural resources for their own gain. Ultimately, the elites of petrostates are talking to each other and creating their own shared culture of excess and luxury.

Kazpost

Kazakhstan’s resources boom has left them economically much further advanced than the other Central Asian states. Nazarbayev is undoubtedly popular for his leadership – whether by good luck or good management – of the economy, and for providing the order and stability that remains prized after the chaos of the 1990s in the former empire. The Kazakh people have a stake in the rising economic tide, but no authorship of it: in 2011, striking oil workers in the western city of Zhanaozen were showered in bullets, killing 14, with many more put on trial tortured in custody.

Khan Shatyr

Ultimately, Astana and the industry it represents has helped to quell ethnic divisions in the Kazakhstan. "Nazarbayev has given the appearance of relying on persuasion, as opposed to coercion”, says Alexander Cooley, an academic who specialises in Central Asia.

The golden towers and the presidential palace

Over on the north bank of the Ishim, a bartender, like almost everyone else in the city, asks what on earth am I doing there. “Just go to Almaty,” he says as we watch the highrise construction workers dance overhead, just far enough out of sight to tell whether they have safety protection. He’s an Almaty boy whose accounting degree brought him reluctantly north. He, like most others, regards Almaty as the capital, and holds little affection for Astana and its elites. "People only come here for money and business," he says. "That’s all."