Related Posts

- By Padraig Reidy on 16 Jun 2017

Shopping centres were the future once. In the 1990s, in America and to a lesser but as dramatic extent, we rewired our cities to allow for the rise of the shopping centre. In Bristol where I (partly) grew up, the centre of the city was abandoned by John Lewis and other major retailers for “The Mall”, a monstrous 1 million square foot concrete box opened next to the M5 in 1998. You couldn’t walk there or get the train, it was accessible only by car.

Britain’s post-industrial era coincided with the rise of the shopping centre. Often these huge buildings with their assorted warehouses and slip roads rose on former industrial sites. Merry Hill in Dudley (opened 1985) was built in a Thatcherite enterprise zone next to the site of the Round Hill Steelworks which, much like most of our industrial heritage, closed as Thatcher’s monetarist medicine took its toll in 1982. Throughout the 80s and 90s the shopping centre craze took hold: Gateside Metrocentre (formerly Europe’s largest shopping centre, opened in 1986), Lakeside in 1990, Meadowhall the same year and Bluewater in 1999.

Shopping centres replaced medium paid skilled work with often low paid unskilled work. But, at least it was work.

Now, according to the same hedge funds that bet against the tottering US housing market prior to its 2008 crash, retail is the next “big short”.

According to the Financial Times, the head of Sound Point Capital thinks “the magnitude of this short could be bigger than subprime”. Shares in Sears, once the darling of US retail, have fallen steadily. The firm has lost two-thirds of its stores in just a decade. Credit Suisse predicts as many as 8,640 major stores with 147 million square feet of retailing space (that’s 70 Westfields) could close this year alone. “Where are we today? Sears is in a death spiral. Malls are dying,” Professor Scott Rothbort of the Stillman School of Business told the FT. That’s in a year of economic growth, falling US unemployment and at least some pay growth.

In the UK, the picture could be more grim. We’re more addicted to online shopping and unlike the US, we’re facing Brexit and a decade of falling real wages. At the moment retail closures have been mostly confined to the high street, but with the closure of BHS, and both Debenhams and M&S issuing profit warnings, the British shopping centre may soon face the same fate as its US counterparts.

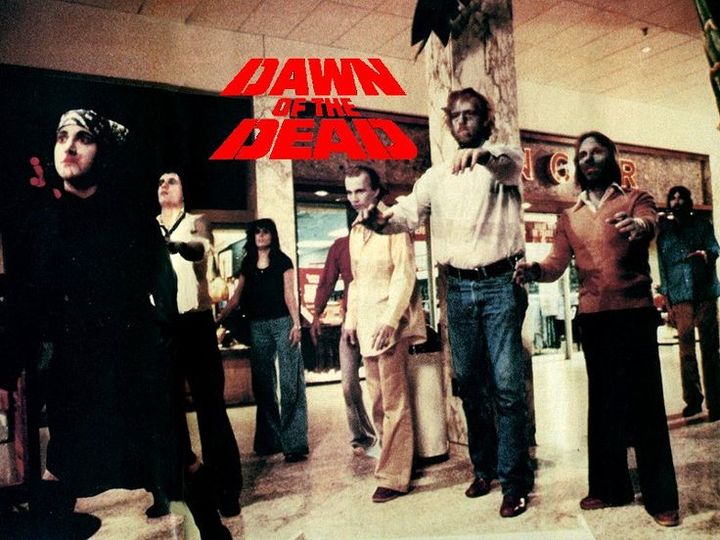

The death this week of George A. Romero, a director who made use of complex feelings about shopping malls in his zombie films, reminded us that our worst fears may not even come close to the real nightmares to come.

For all the horrors of the soulless consumerist experience of the Mall, at least it was a levelling experience bringing together people of different classes and races in a single communal space. Internet shopping with its algorithmic picks and prioritised customer services for those with more money is a lonely individual experience. You may not have been able to afford John Lewis in a shopping centre, but you could at least have a browse.

As shopping centres retreat, we face a future with fewer communal spaces, and still fewer jobs.