Bowie's own reading suggests he can be seen as the fulfilment of a certain Angry Young Man dream

Bowie's own reading suggests he can be seen as the fulfilment of a certain Angry Young Man dream“Why am I so exciting? What makes me dramatic?” – lyrics to “That’s motivation” Absolute Beginners soundtrack

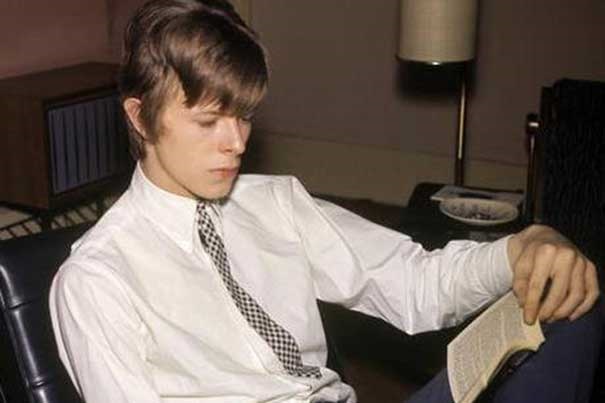

In all the Bowie content being churned out on social media, what jumps out for me is his 2013 list of 100 favourite books posted on his facebook page.

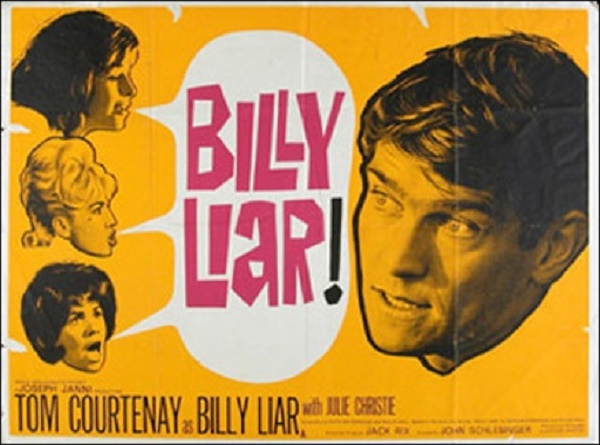

The list is not alphabetical, and it’s tempting to believe it reflects the order in which he wrote them down: Second and third are two novels – Billy Liar and Room At The Top – about northern working class boys in the 50s who dream of making it big and finding themselves trapped by provincial attitudes in provincials towns.

Bowie was a gifted boy who, unlike Keith Waterhouse’s hero Billy Fisher, failed the 11+, but who used the self improvement tools available, like the Observer Book of Music to teach himself to read music. A copy sat in a glass case as an exhibit in the David Bowie Is exhibition at the V&A a couple of years ago.

Whatever the profile of British social realism on the international film festival circuit, the unaspirational reality of Bowie's working class home, came as a shock to middle-class teen girlfriend and fellow musician Dana Gillespie:

“It was [in] a row of houses, which was lots of little houses, the washing might have been hanging out at the back. It sounds mad now because we’ve had insight into working class houses, but you know, early '60s, that lifestyle wasn’t depicted daily on the TV and I had never been to such a house in my life. It was a small place with a couple of big chairs that faced the TV as lots of people’s houses were, and he was rushing around trying to get changed for something – David himself looked like a stranger in his own home.”

The gap between a narrow-minded British suburban then and now is easily forgotten. Billy Fisher is full of big dreams about going to London to be a TV scriptwriter (the Tom Courtenay film version has delightful fantasy sequences), but fear and procrastination paralyse him; culminating (spoiler alert) in that deliberate missing of the midnight train to London.

By contrast Bowie was commuting in to Carnaby Street in his long haired uniform to get spotted, with the same diligence as a would be banker heading for the City. He turns up in incarnation after incarnation of pre-moptop pop band, a teen magazine fashion shoots, an ad for ice cream and posing as a yoof spokesman on a BBC current affairs programmes.

That’s not in anyway to detract from his talent. By contrast that’s what makes him so fascinating. Yes he was the art student, there was the mime training, the student acting, the inspirational borrowing, the reading – always reading everything from great literature to Private Eye – the fearless genderbending. But there was always a cynical playfulness alongside Bowie’s absolute dedication and slog.

Laurence Harvey, who played the bitter, misanthropic anti hero of John Braine’s Room At The Top had already inspired the Rolling Stones’ future manager Andrew Loog Oldham with his portrayal of the dodgy music manager in Expresso Bongo. I’d be amazed if he wasn’t also the inspiration for Bowie’s performance as Vendice Partners in Absolute Beginners, that strange 80s misfire of a music video movie about trying to make it in the era of Tommy Steele and Cliff Richard.

As Julien Temple, who also directed the self-mocking Jazzin’ for Blue Jean video observes, “He had a funny perspective on rock stardom and wanted to take the piss out of himself”.

Even Labyrinth – a film made for and about 12-year-old girls that totally confuses and distresses any Bowie fan who can remember the 70s – has that unbothered 60s Bowie delight in playing with fantasy. And puppets. Check out the dream sequence for As The World Falls Down, which looks like more like Adam Ant’s Prince Charming Videos than anything else. Simultaneously innocent and about sexual awakening, someone told me, seen as a child, it was like a perfect encapsulation of how they imagined the world of grown up parties.

By the time I was raising my own children in the 2000s I was surprised by how much David Bowie had become a presence in the family home. Cited, like a much beloved but absent glamorous uncle as a (selectively presented) role model: for being loyal to friends like Iggy, abandoning fame to go to Berlin and work hard on what really matters. “David Bowie always eats a good breakfast before he goes to parties,” I heard my three-year-old daughter advise her elder brother one day.

For the last 15 years or so Bowie’s was ensconced in Manhattan, a man in his high castle; his quiet life, interspersed with new albums and creative collaborations; often melancholy and haunting but never bitter. Whatever the initial motivation, fame was clearly only the starting point. And as we mourn his passing, I hope we don’t forget the social narrow-mindedness of the world he grew up in, and which he helped transform.