Exile or death: Assad’s campaign against East Ghouta

Image: White Helmet operation in Zamalka, East Ghouta (Syria Civil Defence)

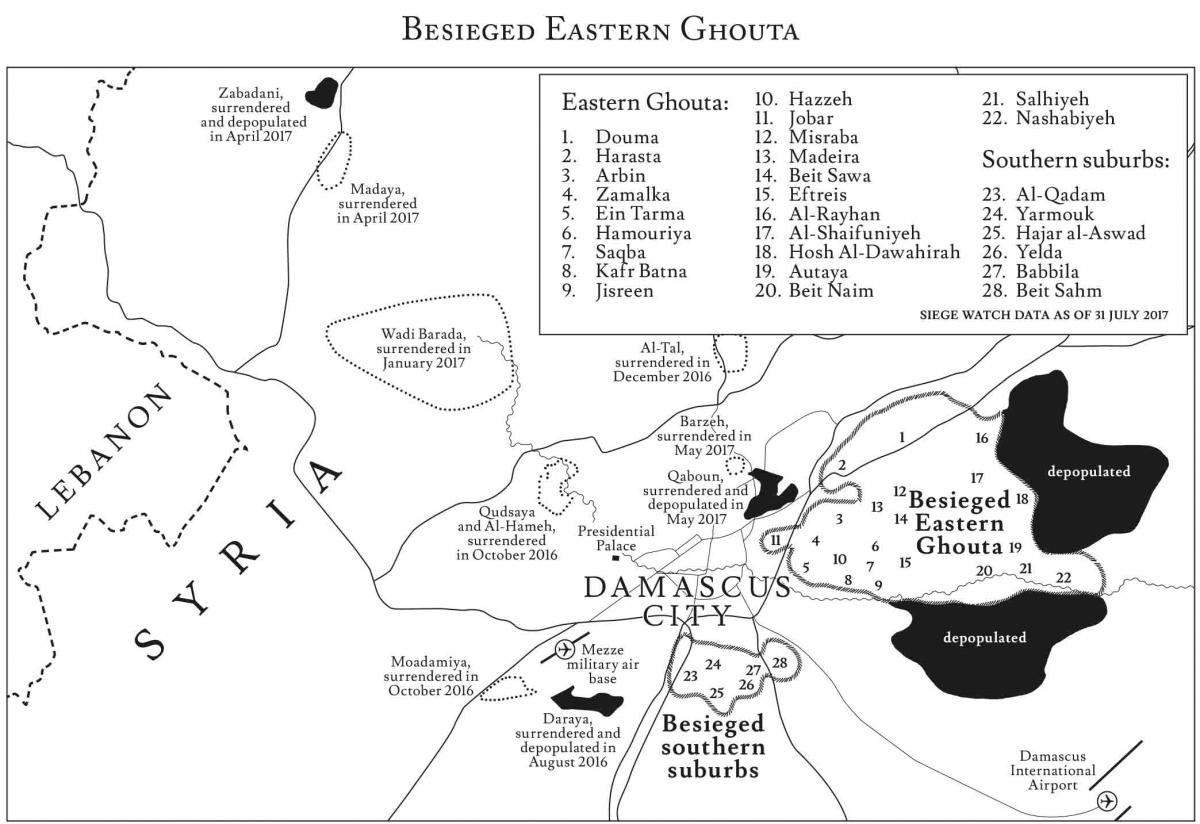

Severely malnourished children are again being seen in Syria’s besieged areas. At the start of 2016, there was an international outcry when malnourished children were reported to be dying in besieged Madaya. This October saw similar dreadful reports emerge from Eastern Ghouta. (PDF map.)

Obeida, an infant, died on 21 October. Sahar, a girl 34 days old, died on 22 October, due to an intestinal infection and related acute malnutrition. Three-year-old Mohammad Abd al-Salem died on 27 October. UNICEF estimate more than 1,100 children are suffering from acute malnutrition.

Eastern Ghouta is under siege by the Assad regime, which is blocking people from leaving, and blocking aid and commercial traffic from entering.

Speaking on 9 November, Jan Egeland of the UN’s Humanitarian Task Force said, “I feel as if we are now returning to some of the bleakest days of this conflict.”

“Nowhere is it as bad as in Eastern Ghouta, which is the area just next to the capital Damascus city.

“This epicenter of suffering has 400,000 civilians, men, women, and children, in a dozen besieged towns, and villages.

“Since September, it has been completely sealed off. Until September when there was some access with the commercial and other traffic. Now the only life-line would be our convoys.

‘This last week we were, again, unsuccessful in spite of all possible efforts to get convoys into these areas with food and medical supplies. The week before we had three convoys overall, including a large one into these areas that got the first supplies in for many months. The week before that, again, we were completely unsuccessful.

“Of course we cannot continue like that: if we get only in a fraction of what is needed, it will be a complete catastrophe.

“The assessment that was done by our colleagues, they were only there for a few hours the week before this, a week ago, showed that there are now a growing number of acutely malnourished children. If you are acutely malnourished, you are very close to dying. That is why we need also the medical evacuation.

“We have confirmation of seven patients dead because they were not evacuated, some of these are children. A list of 29 cases was given some time ago, of 29 cases that are the most critical cases, these will die if they are not evacuated, they include 18 children, and among them young Hala, Khadiga, Mounir and Bassem. They all have a name, they all have a story, they all have the urgent need to be evacuated now.”

On how to resolve the issue, Mr Egeland said: “Of course it is not by evacuating people you solve the problem. The violence has to stop and we have to have general access then we can feed and provide to the 400,000 people.”

History of the siege

Eastern Ghouta is the largest besieged area in Syria. It is an agricultural region of 22 neighbourhoods with a total estimated population of between 376,000 and 425,000. Before the war, the population was more than 1.2 million.

East Ghouta has been under siege from pro-regime forces for over four years. The siege was tightened this year despite the area being included in the de-escalation agreements negotiated between Turkey, Russia, and Iran.

On 21 August 2013, East Ghouta and Moadamiya were targeted by the worst chemical attack of the conflict. Assad regime forces bombarded civilian areas with Sarin-loaded rockets, killing between 1,200 to 1,700 people.

Throughout the siege, the communities of Eastern Ghouta have been subject to conventional air and artillery attacks. Most attacks kill or injure a smaller number of civilians and so gain little attention in the outside world.

One exception was a regime air attack on Douma, Eastern Ghouta, on 19 August 2015. Eight rockets hit two marketplaces and a residential neighborhood. The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) documented 122 people killed, including 11 children, and 485 wounded.

The attack on Nasser Ash’osh elementary killed seven civilians, most of them children

In another single day of attacks, 30 October 2015, at least 65 people were reported killed and 250 wounded in air, rocket and artillery attacks on Douma.

From late 2014, smuggling tunnels connected East Ghouta to opposition-held neighbourhoods Qaboun and Barzeh, but these areas fell to regime forces in early 2017.

Today, basic food and supplies are allowed past checkpoints only at very high prices. Bread in East Ghouta costs 11 times more than in nearby Damascus, according to a Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) report.

Armed groups in Eastern Ghouta

Despite the several announcements of ceasefires and de-escalation agreements since December 2016 the Assad regime has continued to carry out ground and air attacks against both military and civilian targets in Eastern Ghouta.

In June and July there were at least six reports of suspected chemical attacks by regime forces against opposition fighters in Eastern Ghouta and Jobar.

Military control of East Ghouta is mainly divided between two competing armed groups, Jaish al-Islam and Failaq al-Rahman. Jaish al-Islam joined in the de-escalation agreement between Russia and Turkey on 22 July, and Failaq al-Rahman joined on 18 August.

As part of the East Ghouta deescalation agreement, Russia announced on 24 July that its military police had set up two checkpoints and four observation posts. Still the Assad regime’s bombardment of civilians continues.

White Helmets in Eastern Ghouta

Syria Civil Defence, known as the White Helmets, operate throughout Eastern Ghouta, and via social media they maintain a stream of reports on the air and artillery attacks on Eastern Ghouta’s inhabitants.

Through October, they reported attacks killing and injuring civilians across Eastern Ghouta: in Douma, Misraba, Harasta, Madeira, Al-Shaifuniyeh, Saqba, Beit Sawa, Kafr Batna, Hazzeh, and Ein Tarma.

So far in November, Syria Civil Defence in Eastern Ghouta have responded to arillery, air, and incendiary attacks in Douma, Saqba, Ein Tarma, Harasta, Hamouriya, Arbin, Nashabiyeh, Hazzeh, and Zamalka. Several of these attacks killed or injured people, including children.

On 17 November, three White Helmets rescue volunteers – Mohammed Alaya, Mohamed Haymour, and Ahmad Kaeika – were deliberately killed when Assad’s air force targeted a Syria Civil Defence base in Douma, a neighbourhood Eastern Ghouta. On Sunday 19 November, Syria Civil Defence reported that another of their volunteers, Alaa Addin Juha, was killed by a cluster bomb attack in the town of Hamouriya.

Schools under attack

On Tuesday 31 October, up to eight children were killed and others were injured when two schools in Eastern Ghouta were shelled. According to a Syrians for Truth and Justice report, the attack on Nasser Ash’osh elementary school in Jisreen killed seven civilians, most of them children. The attack on Shahid Soheil at-Taklah School in Mesraba killed four civilians, including two pupils.

The attack came the day after a UN convoy had delivered aid. Photographs of the aftermath showed UNICEF schoolbags with the dead children.

Schools have regularly been hit by Assad regime attacks. In 2016, SNHR reported regime attacks on schools in Douma, Nashabiyeh, Hamouriya, and Arbin in Eastern Ghouta, as well as other besieged areas.

On 8 November, Syrian regime forces again shelled a school in Saqba, Eastern Ghouta. This time no injuries were reported.

Medical care under siege

In 2011, Syria had one doctor for every 600 people. East Ghouta now has one doctor for every 3,600 people. Only 107 doctors remain in East Ghouta according to SAMS.

Contagious diseases including salmonella, measles and tuberculosis, have spread. In July, SAMS medical staff reported nearly 600 cases of typhoid.

The blocking of medical supplies by the Assad regime is forcing desparate measures upon medics.

‘We doctors in Eastern Ghouta are taking steps that are medically undesirable,’ Mohammed al-Omar, the head of the surgical department at the Damascus Countryside Specialised Hospital, told AFP.

‘We are re-sterilising most of our surgical equipment, from gloves to tubes and even the surgical blades and sutures—even if it’s for a single stitch.’

In August, four children died waiting for the Assad regime’s permission to be evacuated for medical treatment.

On 23 September, a five year old boy Osama died due to acute herpetic encephalitis. Acyclovir, the antiviral medication needed to save his life, was available just kilometres away in Damascus.

On 10 November, Osama Hassoun, age 20, died of renal failure in besieged Eastern Ghouta, where the dialysis supplies he needed were unavailable. Osama was waiting for a medical evacuation approval that never came.

Eastern Ghouta’s local councils

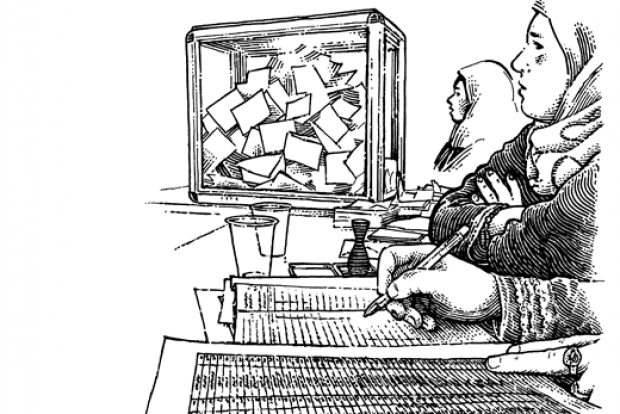

During 2012 the local communities started to self-organise. Up to 26 local councils formed to provide public services and administer local civil and property registries.

The local councils are elected in each area from general assemblies representing the communities. In recent months three local councils changed their election process to public elections, and held free local elections.

Civil society in Eastern Ghouta

Up to 50 local civil society organizations are operating in Eastern Ghouta, active in humanitarian relief, women’s empowerment, child care and protection, skills training, and advocacy. Amongst them are the following:

The Violations Documentation Centre (VDC) has since 2011 been engaged in the documentation of all kinds of violations of human rights by all parties in Syria.

The Office of Local Development and Support of Small Projects (LDSPS) helps projects to re-establish normal life in areas outside regime control by facilitating links with governmental and NGO funds, and training local project managers.

Women Now works on the empowerment of Syrian women in several areas of Syria and the region.

Hurras Network provides psycho-social support and child protection. It began in December 2012 in Daraya.

On 9 December 2013, a group of armed men stormed into the Violations Documentation Centre’s office in Douma and abducted VDC head Razan Zaitouneh, and her colleagues,Wael Hamada – who is also her husband – Samira al-Khalil, and Nazem Hamadi. The four have not been heard from since. The kidnapping took place in Jaish al-Islam’s area of control, and they are held by many to be responsible for the fate of the Douma Four.

In March of this year, Hurras Network was forced to close its office for a time, and staff were threatened by a mob, after an accusation of blasphemy against a children’s magazine based in the same building. Again, the local armed group was believed to be responsible.

‘We are against one group dominating local authority and the security forces. This is what we stood against in 2011 during the revolution and what we will continue to do,’ Alaa Zaza of Hurras Network said.

The UK’s responses to the siege

In 2013, the UK Government put a motion to Parliament deploring the 21 August nerve agent attack on Eastern Ghouta and Moadamiya, proposing that military action ‘that is legal, proportionate and focused on saving lives by preventing and deterring further use of Syria’s chemical weapons’ might be necessary, committing to seeking a UN Security Council resolution in response to the attack, and committing to a further vote in Parliament before any UK military action could take place. The motion was defeated.

Following the 2013 defeat in Parliament, the Government’s responses to Assad’s attacks on civilians have been limited to diplomatic and humanitarian means.

In February 2014, the UK backed UN Security Council Resolution 2139, which demanded that ‘all parties immediately cease all attacks against civilians, as well as the indiscriminate employment of weapons in populated areas, including shelling and aerial bombardment,’ called upon all parties to ‘immediately lift the sieges of populated areas,’ and demanded that ‘all parties, in particular the Syrian authorities, promptly allow rapid, safe and unhindered humanitarian access.’

Resolution 2139 called for monthly reports to the Security Council, and every monthly report since has detailed how UNSCR 2139 and all subsequent resolutions continue to be flouted.

In May 2016, the UK along with other ISSG states negotiated a June 1st deadline for the Assad regime to allow full humanitarian access to besieged areas, with the consequence that the UN should otherwise commence aid delivery by air drops and air bridges. But when the regime failed to meet the deadline, UN agencies then refused to carry out aid dropswithout regime permission.

The regime pressed on with its siege strategy, forcing the complete evacuation of Daraya in August 2016, and the surrender and partial evacuation of other communities.

As the Aleppo siege escalated in late 2016, MPs pressed Government to deploy aid air drops. UK officials held talks with the US Government on air drop options, but they were not put into action.

On 11 January this year, and again on 22 February, the then Secretary of State for International Development told the House of Commons that the Government was still ‘examining all options for getting aid into besieged areas in Syria,’ including the possibility of using drones to deliver aid directly. But while affordable drones are now used for medical deliveries in some African countries, there has been as yet no news of the UK taking practical steps towards such a capacity.