How AT&T shaped modern art

From John Cage to Andy Warhol, the corporate behemoth financed some of the avant garde's biggest names

During the late 1960s and 1970s, a research facility funded by America’s largest telecommunications organisation became a studio of some of New York’s most renowned and avant-garde artists. With access to the facilities, engineers and researchers, Bell Labs turned the research centre into a playground for the likes of John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg and most of New York’s Lower East Side art scene.

Since it was first set-up in 1907, Bell Labs has been at the forefront of scientific invention. During its peak, work undertaken at the labs led to the invention of the laser and the transistor, the birth of information theory and the creation of C, S and C++ programming languages, which form the basis of coding today. Bell Labs has been awarded a total of eight Nobel Peace prizes and every Silicon Valley start-up or global conglomerate has mined the mythology around its unique ability to foster new ideas for clues as to how one research laboratory could consistently turn out such an array of successful technologies.

Owned by AT&T, the successor to Alexander Bell’s Bell Telephone Company, Bell Labs had an enormous advantage over any other type of research facility. It had a wealth of fiscal security, backed by a constant stream of revenue, which enabled it to support and subsidise any project it saw fit.

Immediate returns were never a requirement. The company could hedge its bets by funding multiple projects simultaneously in the hope that a fraction of them would be realised and be developed into a marketable product.

By 1925, after only 17 years of operation, the Bell Telephone Company research department had grown to more than 3,600 employees and branched off to form its own organisation. It merged with Western Electric, which ran the Thomas Edison lab in Menlo Park, New Jersey. Often thought of as Edison’s unsung contribution to science, his research department sang from the same hymn sheet as Bell; they were both trailblazers of invention.

Bell’s ethos was simple. It gave its employees the space and independence of mind needed to work on ideas as they saw fit. The management team saw their role as more than just administration. They wanted to foster a new type of collaborative work environment. In short, the engineers and scientists at Bell were allowed to take an idea and run with it.

If an idea is clear, simplicity will travel throughout the product

Under the watch of Mervin Kelly, who rose up the ranks from researcher to become director of the organisation from 1951 to 1959, the lab turned from a research centre to a ground-breaking factory of ideas. His often radical attempts to get his workers to step outside their normal work habits saw the director implement a different kind of management.

He gave his employees autonomy, rarely pulling rank and instead encouraged the questioning and testing of the company’s’ most prestigious minds by new or junior members of staff. He instructed all employees to work with their doors open and even put his job on the line in order to grow his beloved organisation.

Twice he handed in his resignation because he felt integral work at the centre was being underfunded. On both occasions, AT&T coughed up the funds at the 11th hour.

But the crusade to create new technologies didn’t stop at telecommunications. The staff at Bell Labs, especially Billy Klüver, didn’t want their research simply to produce machinery that solved mundane problems. They wanted to create new types of inventions. Ones that didn’t just solve existing problems but that created a whole new way of doing things.

Focusing on sound, communication and early film, the Labs originated a pioneering work ethos – that quantity doesn’t always correlate with functionality. Later identified in Richard Gabriel’s seminal text Worse is Better or New Jersey Style, the idea is that simplicity is the key. Being right is important too, but if an idea is clear, simplicity will travel throughout the product and the implementation of the product. In other words, tackling complex problems by solving them with clear, sharp designs. But before you can solve the problem you need to identify it, and working within the confines of a lab has its drawbacks. Scientists are restricted to experimenting with assumptions and can only solve issues of which they’re already aware.

As the ethos took off, throughout the 1960s the lab became a conveyor belt of success. But the staff wanted to branch out and work with practices not usually associated with the analytical approach and rigour associated with engineering. They wanted to embed researchers in real-world situations, to try to break out of the stale lab environment.

What happens when you partner Andy Warhol with an electrical engineer?

At the same time in Manhattan, the Lower East Side saw an explosion of creativity. Studios and galleries were set up in rent-controlled loft apartments. Artists were turning the art world on its head, and catching the attention of the world’s media. But although all this was a stone’s throw away from Bell Labs, the two worlds never interacted, until Bell recruited an assistant professor of electrical engineering from Berkeley.

Born in Monaco, Billy Klüver was educated in Sweden and spent his early twenties working at as an engineer for a large electronics company in Paris. There he made a name for himself by installing a television antenna on top of the Eiffel tower and by developing underwater filming equipment for the conservationist and explorer Jacques Cousteau. After moving to the US to do a PhD, Klüver was brought in to work in the laser department at Bell Labs but became frustrated. While working at Bell, he started to approach and collaborate with artists, which is where he first came across Robert Rauschenberg.

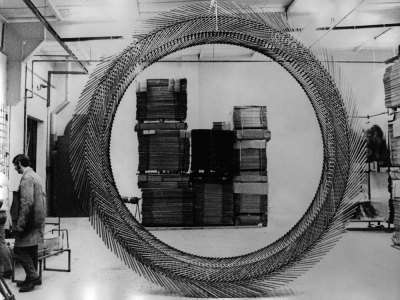

Klüver’s first collaboration, a kinetic sculpture that slowly destroyed itself, premiered at the gardens of the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1960. Artists were invited to contribute their own work – and Rauschenberg approached Klüver with a proposition. He needed help in producing a wireless device and was brought in to discuss a potential collaboration.Klüver and Rauschenberg identified a need for engineers and scientists to work in tangent. In 1965, they devised EAT (Experiments in Art and Technology). Klüver later said he thought artists “helped make technology more human”. The programme opened up facilities at the lab, often out of hours, to an array of artists, performers, composers, filmmakers and choreographers. In return, lab staff were included in often ground-breaking work designed not for everyday use but for the sake of art.

They began with 30 engineers, each partnered with a different artist and instructed to produce a piece designed for a one-off performance intended to encourage an on-going partnership. As the experimental assignments began to take form, they started to attract the attention of notable names, from Claes Oldenburg to Andy Warhol.

In the same year, the collective was established, Klüver approached the Stockholm Festival of Art and Technology, where he already had connections from his time as a student in the city, to collaborate on their annual festival. It would take place in the technical museum in Stockholm, with the backing of Fylkingen, one of the world’s oldest societies for experimental music and arts, and the Stockholm daily newspaper Dagens Nyheter.

EAT’s ability to take on socially-orientated commissions with an artistic edge led to a string of projects across the world

In 1966, over the course of nine days, performances, ranging from theatre to sound design, would be open to the public. The star-studded lineup, included the avant-garde composer John Cage, the dancer Lucinda Childs, the Swedish multimedia artist Öyvind Fahlström, the experimental choreographer Deborah Hay, the minimalist filmmaker Yvonne Rainer and others – including Robert Rauschenberg himself. The schedule also included talks by some of the artists and researchers at Bell Labs.

But as the project grew so did the budget. As part of the commission from the festival, Fylkingen paid $3,000 up-front with an additional $7,000 due on proof of how the initial money was spent. When no proof was handed over, a legal battle ensued and the project came to a halt. In an open letter from the Swedish collective, they blamed EAT’s obsession with its own reputation. “You Americans seem to expect us in Fylkingen to pay large amounts of money just to create a platform for your own work in the USA… we just have to be content with any crumbs of fame that may fall from your table.”

With nine commissions already in development and nowhere to showcase the work, Billy Klüver moved the event to the 69th Regiment Armory in the lab’s hometown of New York, where it ran from 13 to 23 October 1966. It included robotic performers, remote-controlled carts and phone booths piping out transmissions from hotel kitchens and police radio bands located around the city.

One of the founding ideas for the programme was that it could be used as a model to roll out and be franchised into a network of centres, employing engineers to assist artists with their work. Setting up artists with a suitable engineer came with no creative caveats. Regardless of artistic merit or of an artist’s scientific background, EAT’s only objective was to openly encourage unusual or complex proposals.

EAT was intent on global impact. After establishing its headquarters in a loft on East 16th Street in New York, EAT employed the executive director of Bell Labs to act as an agent on behalf of the programme. By 1969, EAT had collected around 4,000 members, both artists and engineers.

Bell Labs was packed with sophisticated computers and film editing equipment not accessible anywhere else. This allowed artists to experiment with early computer-generated graphics and later led to a breakthrough in on-screen graphics, which began with an office prank and ended up splashed all over the press.

One day, while working in the labs the artist Ken Knowlton, together with Leon Harmon, a researcher in neural processing, decided to play a prank. While a senior colleague was absent, they covered his office wall with small black-and-white photographs, which when viewed from a distance, created a large image of a naked woman. The technique, later defined as BELFLIXS, and credited as a rudimentary form of pixels, became an instant media hit. When the prank leaked, the lab was quick to rubbish any relation to Bell, but after it was lauded at a press conference hosted in Robert Rauschenberg’s loft apartment and the image made the front page of the second section of the New York Times, it quickly reversed the decision. In an essay published by the YLEM journal in 2005, Knowlton described the public relations battle:

“The PR department huddled and decided, so it seems, that since she had appeared in the venerable Times, our nude was not frivolous in-your-face pornography after all, but in-your-face Art. Their revised statement was: You may indeed distribute and display it, but be sure that you let people know that it was produced at Bell Telephone Laboratories, Inc.”

In the future, will men wear neckties?

As the press began documenting the sensational stories coming out of EAT’s partnerships, influential individuals, private corporations and even government departments came knocking at the door. EAT’s ability to take on socially-orientated commissions with an artistic edge led to a string of projects across the world.

In 1979, EAT called for submissions for its Projects Outside Art, seeking out artists working with social and public concerns such as the human and natural environment, education, the distribution of food, and the democratisation of leisure.

From early attempts at networked communication to the development of instructional software for satellite television in rural villages, EAT worked with partners in developing countries and global cities to address new ways of storing and sharing communications.

One project, Telex: Q&A, saw EAT set-up public telex machines in Stockholm, Tokyo, New York and Ahmedabad, India, where they invited people to ask each other what the world would be like in ten years. A sample of the questions, digitised by the Daniel Langlois Foundation in Quebec, includes a variety of propositions: What will rents be like? Will pot replace alcohol? What will replace pot? Will there be a difference between work and leisure? Will men wear neckties?

In January 1972, on request of the division of culture of the ministry of education in El Salvador, EAT conducted research into mobile broadcast television production equipment and later used the research to devise methods for recording indigenous cultures.

And in 1971, while undertaking a project at EAT, the artist Robert Whitman developed the Anand Project, an interdisciplinary team dedicated to creating methods for instructional television programming for villages around the Anand Dairy Cooperative, Baroda, India.

The themes explored during his time with EAT resonated with Whitman throughout his career, as it did with most of the artists who called the collective home. In 1972, Whitman produced his first telephone piece, NEWS, in which participants using pay phones called in reports that were then broadcast live over radio station WBAI.

None of the work at Bell would have been possible without the funding from AT&T. What began as a manufacturing company, producing switchboards, telephone cables and electronic amplifiers, grew into a massive operation. By the mid-1980s AT&T had a monopoly over voice and data communication in much of the world, providing all the local telephone services in the United States and having almost total control over the country’s communications industry.

But in 1984, the US government caught up with AT&T. The authorities suspected the company was using profits from a subsidiary to fund its network, and began a lengthy legal battle that resulted in the breakup of AT&T, and the company’s stranglehold on America’s communications. As AT&T’s profits began to decline, so did the lab’s output.

The communications giant had such a grip on the market it had never really had to sell anything, so when the inevitable happened and AT&T was forced to compete with new companies and a burgeoning tech industry in Asia, it was forced to downsize. The best minds began to haemorrhage west, in the direction of the startup sanctuary of California, and EAT’s resources slowly dried up.

EAT was never confined to Bell Labs: Klüver always feared it becoming institutionalised. To him, success wasn’t about becoming the poster boy for contemporary art, but to destigmatise the use of creative thought in engineering. If EAT were truly successful, it wouldn’t need to exist.

Despite leaving Bell Labs in 1968, Klüver was always at the helm of EAT’s operations. Once Bell fell into financial difficulties EAT became a one-man crusade.

In an interview in 1995, the engineer described how EAT was still going strong: “Once the engineer and the artist get to talk together if there is anything there – it will happen. If there isn’t, it will die in ten seconds. It’s happened that way for over 30 years.”

Klüver continued to operate the service of partnering artists and scientists until the summer before his death in 2004.

EAT was a unique force. It stood on the shoulders of AT&T’s colossal empire to form a one of a kind anarchic research centre. Looking back at his time at EAT, Knowlton acknowledged the collective’s bizarre bond between rampant unregulated capitalism and avant-garde artwork: “What happened there would have baffled millions of telephone subscribers who, knowingly or not, agreeably or not, supported the quiet circus.”