Labour’s eternal rift: the pub or the party

For as long as there has been a British Left, its appeal to those who would benefit most from its success has been limited by the suspicion that many of its adherents are, frankly, a bit odd. For a movement that seeks to represent and mobilise the majority of the population, prominent left-wing leaders and activists have often had niche interests and esoteric concerns. This characteristic has grown more prominent in recent years, as trade union and local government decline has resulted in fewer “ordinary” people at the apex of the Labour movement, while the rise of the hobbyist Left has brought about an ascendancy of cranks in high places. “There used to be a broad spectrum of people in the [Parliamentary Labour ” recalls Larry Whitty, “but no longer. The professionalisation of politics hasn’t helped. There are plenty of people whose sole intention is to become an MP.”

This has led to a host of rather boring careerists, where once there might have been charismatic campaigners, but it has also resulted in a preponderance of people who, while not strictly careerists, have leisure pursuits and personal peccadillos largely alien to most Britons, especially to the working class.

A hundred years ago, Lenin used the term “Labour aristocracy” to denigrate the better-off, better-paid workers who sided with the bourgeoisie against the proletariat and thus hindered revolution in countries such as Britain. In reality, it was the more secure workers in skilled occupations who were most likely to be in trade unions and most likely to vote Labour, while the unskilled, casual workers had lower rates of unionisation and would often vote Liberal, Tory or not at all. Today, there are new “Labour aristocrats” on the scene, contaminating the image of the Left among its natural supporters, and hampering the cause of socialism in the UK. Instead of being composed of miners and engineers, this new aristocracy is filled by the ranks of the hobbyist Left, who proudly assert their elite culture and esoteric concerns, and look with contempt upon the values and leisure pursuits of the masses.

A conservative class

Cultural conservatism is a notable feature of most people across the world – and this is as true of those in modern industrialised economies as it is of those in developing nations. Whether Maasai herdsmen or Surrey stockbrokers, people tend to be wary of change. This is particularly so when it comes to their traditions and pastimes. The majority of society may well eventually adopt the habits and tastes of the avant garde, but in any given generation, cultural elites are isolated, ridiculed and often despised.

This cultural conservatism is particularly pronounced among traditional Labour voters in the UK. Over 70 years ago, the long-time trade unionist and Labour politician Jimmy Thomas wrote that “the workers are more conservative than the Conservatives”. Describing the inter-war growth of the Labour Party, as working men and women switched their allegiance from the Liberals and the Tories, the historian Martin Pugh writes of the sentiments of “a conservative working class that, in certain circumstances, was prepared to vote Labour”.

By the 1960s Richard Hoggart – author of The Uses of Literacy and one of the founders of cultural studies – observed that “the more we try to reach the core of working-class attitudes, the more surely does it appear that that core is a sense of the personal, the concrete, the local; it is embodied in the idea of, first, the family, and, second, the neighbourhood.”

Meanwhile the Marxists of the New Left, such as Perry Anderson and Thomas Nairn, attacked the “bovine” nature of the English working class, with their “ill-conceived attempt for equality and bottomless philistinism”.

Clearly, this was not the case for everyone. Specific regions bucked the trend: some areas such as the coalfields of South Wales and North East England, or the textile districts of West Yorkshire and East Lancashire, were home to a proud radical tradition, often arising from the coinciding of religious non-conformist religion with skilled jobs in staple industries. In these areas, workers who were concerned more with the chapel and library than the pub and the music hall might be in step with the priorities of the wider community. Nonetheless, this tradition was generally absent from large areas of West Lancashire, London, the Midlands, and most Southern towns.

Pleasure, amusement, hospitality and sport

As the historian Gareth Stedman Jones argues, there was a distinct lack of this tradition among the radical artisans in London. Fellow historian Elizabeth Ross describes a pre-war East London where “Church goers often had to face choruses of mockers”, and one convert walking with a missionary in South West Bethnal Green in 1889 was assaulted by former drinking companions.

The impression conveyed by Salvation Army founder Charles Booth’s survey of the turn of-the-century London poor was of a working-class culture: “Both impermeable to outsiders, and yet predominantly conservative in character: a culture in which the central focus was not “trade unions and friendly societies, cooperative effort, temperance propaganda and politics (including socialism)” but “pleasure, amusement, hospitality and sport.”

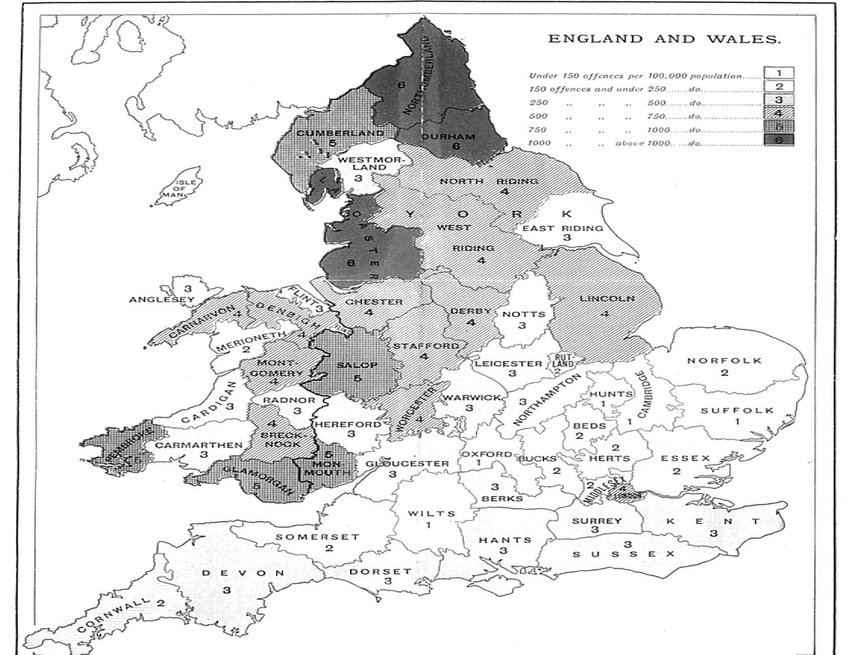

According to an 1899 map depicting the ‘Distribution of Drunkenness’ in England and Wales, the North West and the North East had the highest rates of convictions for drink-related crimes, with over 1,000 offences per 100,000 people. In contrast, most of the South of England had fewer than 250 offences per 100,000, apart from London, which featured between 500 and 750 offences per 100,000 people. Port cities, which featured high levels of the casualised labour that inhibited left-wing recruitment were particularly well-oiled: in the Addison area of Liverpool in the 1890s, fully one in every seven shops were licensed properties, while in the Hard district of Portsmouth, 13 out of 27 premises had a licence.

Of course, there are limits to all generalisations, and there were always exceptions to apparently homogenous cultures. In inter-war Salford for example, far from being an omnipresent background to daily life, “people took part in pub culture when they could afford to”; and although football was enormously popular amongst working-class men, very often people could not afford to attend matches featuring Manchester United or Manchester City, and had to make do with more humble grassroots teams.

Yet over all, most working-class areas exhibited a culture centred on the pub, the music hall, sport, family and patriotism, which often inhibited their recruitment to socialism, given that many left-wing activists took a dim view of that same culture.

For example, the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) – the leading socialist society in London – never had more than three thousand members out of a population of more than six and a half million.

Of London, Stedman Jones concludes that the “republican and international culture which had been such a characteristic feature of artisan tradition in the first three quarters of the century had all but died out by 1900.”

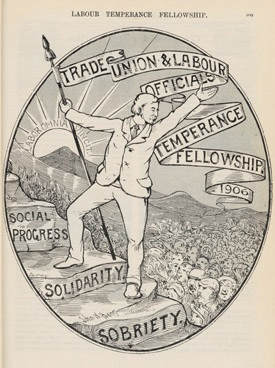

Control of alcohol was traditionally a big concern for some in the Labour movement. Yet the broader movement for restriction of liquor had its roots in the disciplinary priorities of the new industrial workforce. Historian John Greenway describes how:

“The new urban elite of iron masters, factory owners and the like had a direct social and economic interest in increasing the efficiency and security of their workmen. These were to form the backbone of the temperance movement. As society became more mobile and fluid, and as the effect of industrialisation and urbanisation was to multiply the opportunities for the fulfilment of individual desire, so the response was to promote new measures for regulating those passions by the governing classes.”

The First World War occasioned the first major reform of licensing in decades, and these restrictions were generally accepted as a necessary evil to aid in the successful prosecution of the war. Most restrictions on beer had been relaxed by mid-1919, but there was anger at the continued state interference given the end to hostility. In early May 1919, the hard-drinking dockers’ leader and MP for Salford North Ben Tillett complained that it was an unacceptable infringement for his constituents to unable to obtain liquor on Easter Monday, which had caused “serious discontent” and was fast “becoming a scandal [that] interferes with the disciplinary work of the Union”.

After World War One, the per capita consumption of alcohol nonetheless continued to decline, and the issue of licencing reform gained traction at the top of the Labour Party; Clement Attlee proposed that the sale of alcohol in the “New Towns” built after the Second World War should be under state control, but ultimately few Labour MPs saw alcohol as a major issue, and the issue faded in the 1950s.

‘The world is not a huge Sunday school’

Many early Socialist proselytisers – notably the editor of The Clarion newspaper, Robert Blatchford – were well aware of this problem. Ruminating on the issue in an article entitled “Why Labour and Socialist Papers Do Not Pay”, he asked: “Is it because the working people don’t know what’s good for them; or is it because the Labour and Socialist journals do not know what the working people want? Men like ourselves…always make the mistake of assuming that the millions of British workers have tastes, interests, habits of minds and concentration of purpose exactly like our own.”

After calling for more sports reportage in left-wing newspapers, he concluded:

“I think the chief reasons why Labour and Socialist papers fail are, firstly, that they give the public too much Labourism and Socialism, and, secondly, that in the nature of things they appeal to a small minority of the people. The kind of daily paper that might succeed, if it were backed financially, is, I think, a bright newspaper of broad and comprehensive general interest with an editorial brief for Socialism or Labour.”

This argument was summarised in a leading article from October 1915, which concluded: “It is the fault of those who do not understand The Clarion that the very name of Socialism is despised and detested by the great mass of British people.”

While successful recruiters for socialism such as Blatchford blamed cultural differences for the limited appeal of Labour, those with an orthodox Marxist standpoint, such as the Plebs’ League, often took a different view. In most cases, they were frustrated and antagonised by the apparently obnoxious and pig-headed nature of much of the working class. In a May 1917 editorial in Plebs magazine addressed “To Our Critics”, they claimed that the difficulties of the labour movement could be overcome if only the workers spent more time studying economics, and learned to view the world from a more scientific and logical perspective.

A piece by Frank Jackson in the same publication in August of that year went further. Attacking the “contention that the weakness of the Labour Party is that it is not as it should be, the Party of all Workers”, Jackson argued that this was “scarcely a criticism of the Labour Party; since the Constitution of that body makes it abundantly clear that, if it is not the Party of All Workers, then it is the Workers’ and not the Party’s fault.”

It was this contemptible argument – that workers should naturally move towards the labour movement but were too obtuse to know their own best interests – which the most successful socialist proselytisers fought against. They knew full well that to convert the mass of the working classes to the Left they needed to offer pragmatic and practical means to achieve palpable goals, whilst rooting their appeals in the local culture and vernacular. In the words of one C Brown, whose letter appeared in The Clarion in March 1916: “What we shall need to keep before us will not be so much of Marx, or even [NUR President Alfred] Bellamy, but of [William] Morris.”

Railway trade unionist Charlie Cramp wrote a strongly-worded letter to Railway Review on exactly this subject in May 1916. After asking why the people did not understand the radical-left Independent Labour Party, he argued that it was because the ILP “does not understand the people”:

“One of the most important things is…to learn that the world is not a huge cosmopolitan Sunday school, but a planet peopled with men and women who are the heirs of instincts, habits, and frailties accumulated by the race through ages of pain and striving. The Socialism which they will adopt will be as an easy-fitting garment, not a straight-jacket composed of fads intended to restrict their liberties; and all the time that ILP MP’s [sic] run after Temperance Bills…and other Liberal nostrums, the people will not understand them.”

This point about Temperance Bills was alluding to the common Liberal aspiration – shared by many socialists – to curb alcohol consumption. But this attitude towards drink was largely crafted by religion, region, and class. In London, “a bar was a normal fixture in radical workmen’s clubs and provincial socialists were often shocked by the SDF’s tolerant attitude towards beer.”

While many socialists with impeccable working-class credentials were temperance reformers, overall they were in a minority, and thus attempts to restrict drinking had the indelible stamp of middle-class interference, something seized on and exploited by the Conservatives. Thus in April 1915 The Clarion thundered that “Socialism is to the bulk of our people a novel and foreign idea. One is sufficiently handicapped by an open championship of Socialism without having Labourism, Pacifism, Little Bethelism, Teetotalism, Anti-Patriotism, Pro-Germanism, and all the fantastic vagaries and flatulent sentimentalities of the Lib.Lab. rump stuck in one’s hair like straws.”

Alongside The Clarion’s Blatchford, one of the great working-class socialist agitators of the time was the aforementioned Ben Tillett. He had a long history of struggle for working men and women in Britain, and suffered violence and the hands of employers and the police.

His greatest asset was his ability to speak directly to the ordinary concerns of the working class, and in a language they understood. Writing of his memories of Tillett in the 1950s, Graham Thompson remembers: “Ben Tillett had the indefinable gift; in common with the greatest of the old time music-hall performers and actors generally, of being able to do anything with an audience with a look or a gesture.”

Another anecdote from SF Whitlock neatly encapsulates the differences between the rambunctious, demagogic Tillett and the sober and abstemious gentlemen more typical of the Labour leadership: “At a Labour Conference the headquarters was in a large hotel. In the lounge sat Ramsay MacDonald, Arthur Henderson, Philip Snowden + other self righteous leaders, when in comes Ben Tillett, with one of the gayest birds in town, + went upstairs with her.”

The Tories had long attempted to exploit working-class culture, and the unease of many on the left with boozing and sport. According to Jon Lawrence, in late-Victorian and early Edwardian England, local Tory candidates in Wolverhampton obtained a ‘stranglehold’ over Wolverhampton Wanderers Football Club, and appealed to local working-class voters through this connection. Likewise, in Liverpool the President of Everton Football Club, Jon Houlding, also one of the city’s leading brewers, used his connections with sports and beer to secure votes.

Later, in the decades before and after the Second World War, some on the Left began to use ‘Tory’ methods of winning working-class support. Daryl Leeworthy has shown how local Labour parties in Wales used sport to win votes, through clubs such as the Splott Labour Amateurs and the Brynmawr Labourites and assistance to acquire playing fields. The Labour MP David Lewis Davies, who represented Pontypridd between 1931 and 1937, was a former chairman of the parks committee and was responsible for developing a variety of sports in the local area.

By the 1930s the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) was trying to harness leisure aspirations, and between 1938 and 1945 beer consumption actually rose, from two million to three million barrels.

I read the news today...

Meanwhile, the historian Keith Gildart argues that Liverpool’s working-class “created a popular culture that could be found in the home, street, pub, club, concert hall and football stadium.”

For Gildart, this culture was vital to challenging the existing social, religious and political divisions and enabling Liverpool’s long transition from a bastion of working-class Conservatism to the Tory desert it is today: “The attitudes of Braddock, Heffer and other labour movement activists in relation to the Beatles offers a counterpoint to the traditional characterisations of socialist attitudes to popular music.”

One of the ways in which political hobbyism relates to music is the notion that great music is not only written by left-wingers, but is itself inherently radical. Yet an examination of musical history reveals that that is certainly not the case. For example, in the Beatles’ song Paperback Writer, the aspiring novelist is working for the Daily Mail. It was through a January 1967 edition of the same newspaper that John Lennon learned about 4,000 [pot]holes in Blackburn, Lancashire featured in A Day in the Life. A month later the same paper carried the story that provoked Paul McCartney to write She’s Leaving Home. All of which begs the question: why did the most revolutionary and influential group of the 1960s – the paradigmatic radical decade – spend so much time reading the Daily bloody Mail?

Apparently the Mail was Lennon’s favourite paper, something I can easily believe – if Lennon were alive today I have no doubt that he would have become an embittered reactionary; for proof of this see the political transformation of Morrissey. Traditionally assumed to be on the Left, the former Smiths frontman has become increasingly right-wing in recent years, supporting Brexit and wailing against immigration. He is also resident in Ireland for tax purposes, thus denying the UK welfare state much-needed funds, and – perhaps most unforgivably for many Smiths fans – is a full-throated supporter of Israel.

Compare Morrissey’s behaviour with that of the late George Michael, never as cool as his fellow ‘80s singer, but a secret philanthropist, who in addition to giving millions to charity also helped countless individuals with smaller sums. This is similar to the respective fates of Hall and Oates and Queen – back in the ‘80s, the former refused to tour apartheid South Africa, while the latter did so willingly. Nonetheless, today it is Queen that are (relatively) critically respected, while Hall and Oats are often the punchline of a joke.

Working man in Hammersmith Palais

The hobbyist conception of pop and politics perhaps found its apogee in punk. Yet punk itself has been massively overhyped both in terms of its appeal to young Britons at the time, and in terms of its anti-establishment credentials. According to Gildart, glam rock “was arguably more politically and socially transgressive and generated a much broader popular appeal” than the punk rock that followed. Furthermore, glam rock “did not represent a flight from class but was a restatement of its collective values and hedonistic cultures.”

Writing at the time of punk, Dick Hebdige noted at the Clash’s performance at the Rainbow, although seats were ripped out and thrown at stage, last two rows were entirely occupied by record company executives and talent scouts, and CBS, the Clash’s label, paid for the damage without complaint. For Hebdige, “there could be no clearer demonstration of the fact that symbolic assaults leave real institutions intact.”

Dave Haslam has one grizzled old rocker claiming that punk was “championed by the music press who needed a new gimmick. I think the Clash were the only ones with any talent”, and Marco Pirroni told punk writer Jon Savage that the Sex Pistols’ appearance on the Bill Grundy show “was the end of it for me really…From something artistic and almost intellectual in weird clothes, suddenly there were fools in dog collars and “punk” written on their shirts in biro’.

Nor was punk appreciated by the labour movement at the time. Sixteen female members of the TGWU at the EMI Records dispatch plant in Hayes, Middlesex, refused to handle any material produced by the Sex Pistols after witnessing the Grundy interview. In this they were supported by members of the Electrical, Electronic, Telecommunication and Plumbing Union (EETPU). For Gildart, this reveals that working-class women trade unionists in the mid-1970s were using industrial militancy not only to gain wage equality; they were also willing to withhold their labour in order to preserve a particular notion of femininity and working-class respectability.

The local Labour parties in places such as Derby and Newcastle also criticised the decision by venue-owners to allow the band to perform. According to Gildart, this criticism was couched in terms of a lament for a “working-class world we have lost”. Yet at the same time, to the chagrin of Labour leaders, “a particular section of working-class youth was rescinding its traditional loyalties. The rhetoric of the Sex Pistols and the basis of their appeal were indicative of such a process.”

The fantasy electorate

Back in 2001, Jon O’Neill identified a convergence of post-modern leftism with the neoliberal ideas of the market, and warned that there was a real danger of winning cultural battles but losing the class war. Today, this danger seems more apparent than ever, but it has been a long time coming. Historically, elements of the British Left have been ill-at-ease with mass culture, but this trend was counteracted by the ballast provided by the weight of numbers of ordinary workers. Today, as the composition of the Left shifts, there is an increasing dissonance between the culture of the hobbyists and the mass culture.

Most people barely read any books. Most people have terrible taste in music and love “comedy” barely deserving of the name. Any illusions hobbyists have about the electorate would be swiftly dispelled if they switched on a daytime quiz show or watched a few minutes of the highest-rated TV shows. All of this is perfectly fine – there is nothing particularly virtuous about being well-read or having a refined taste in music.

More importantly, there is absolutely no need to have a cultured electorate in order to effect radical change. The problem is when left-wing hobbyists insist that the mass of the electorate are actually just like them, and that it is indicate of class hatred to say otherwise. The hobbyist Left has an idealised vision of the electorate. But not only does this fantasy electorate not exist, it does not need to exist to have a genuinely transformative socialist government.

This is an edited extract from David Swift’s A Left For Itself: left-wing hobbyists and performative radicalism, available now from Zer0 Books