Architect Mickey Muennig has lived in relative anonymity in California’s ruggedly scenic Big Sur area for over 40 years. Yet he is widely revered as a hugely influential if unsung pioneer of California’s iconoclastic organic architecture movement.

It’s not surprising that this flourished in California, given its history of eccentricity.

From the 1950s, bohemians and rebels, including writers Henry Miller and Jack Kerouac — a leading light of the proto-hippie Beat Generation — were drawn to Big Sur’s wild, sparsely populated coastline. Just as unconventional were the first defiantly curvilinear, eco-friendly dwellings — created by mavericks such as Muennig — which sprouted there soon after.

Typically, these were integrated into the landscape, made of recycled and natural materials and experimented with solar power. Many were built partly underground so they didn’t impose on their surroundings or were dramatically cantilevered over vertiginous clifftops to drink in the spectacular views of the Pacific.

Muennig’s own creations include a 22ft-wide wine barrel transformed into a house, a flying saucer-like bachelor pad and a holiday home shaped like a Greek village that hugs a near-vertical slope.

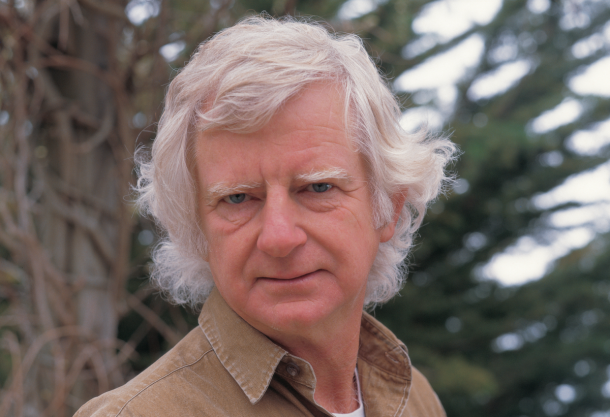

Laid-back, short and white-haired — and consequently nicknamed "The White Elf" by locals — Muennig fell in love with the Big Sur while holidaying there in 1971.

Idiosyncratic though his buildings are, they weren’t created in a vacuum but reflected a huge cultural sea change then shaking up American society — its late 60s/ early 70s counterculture. Integral to this were the era’s burgeoning, interlinked ecology and back-to-nature movements, whose influence was immense.

In November 1969, the New York Times reported that a concern for the environment was "on its way to eclipsing student discontent over the war in Vietnam". By 1970, thousands of young, mainly middle-class Americans had fled the cities with the commercialisation of such hippie heartlands as San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury.

Empowering them to escape their country’s polluted, soulless cities was the affluence of the post-war boom years. This gave them an unprecedented freedom of choice to reject what they saw as the materially rich, spiritually poor world of their parents’ generation and seek alternative lifestyles.

Various seminal, eco-publications fuelled the phenomenon of hippies choosing to drop out and living in close harmony with nature, free from the restrictions and persecutions of the state. There was the Whole Earth Catalog, the countercultural bible which, from 1968, had been both spreading the eco message and providing "access to tools that would enable the reader to "shape his own environment", among other things. Similarly influential was Lloyd Kahn’s 1973 book Shelter. This celebrated architecture of the ancient past, for example that of the Native Americans, which utilised traditional skills and natural materials — another major influence on the Californian self-build craze. In the same spirit, in 1970, the magazine Mother Earth News published a "Back to the Land" issue that included features on "finding a place in the country, laying out your homestead, building a house, raising your own food…"

One of the earliest manifestations of this self-build, neo-homesteader trend was Drop City in rural Colorado, a commune housed in geodesic domes set up in 1965 and inspired by a lecture given by architect and hippie hero Buckminster Fuller.

Although marginal at first, the ecology movement, along with self-build architecture, moved nearer to the mainstream in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis. The acute shortages caused by the latter were a call to arms for the conservation of fuel and research into renewable energy sources, forcing governments and public institutions to take action. The US saw a surge of experimentation with everything from solar and wind power to the use of recycled materials in both municipal and domestic spheres.

And Muennig himself, who remembers "becoming a hippie real fast" soon after settling in the Big Sur, was at the vanguard of this desire to innovate. Incidentally, the experimental self-build movement went hand in hand with a growing anti-modernist, anti-rationalist approach to architecture that increasingly held sway in the 70s, not only in architecture but in all areas of design.

Born in Missouri, Muennig, whose father worked in a dynamite factory, initially studied aeronautical engineering, then became passionate about architecture. On hearing about the eccentric, eclectic, fantastical work of architect Bruce Goff, a tutor at the University of Oklahama, he transferred there, finding huge inspiration in Goff’s ideas.

These ranged from Rapunzel-inspired towers and carpeting used outside as well as inside houses to modernist, glass constructions. "His classes involved reading fairy tales, looking at Japanese prints and listening to Ravel and Debussy," Muennig once recalled. "But he explained architecture very thoroughly on the rare occasions he talked about it.

A friend and mentor of Goff’s was Frank Lloyd Wright, whose buildings, such as his 1935 house Fallingwater — which juts over a waterfall — sowed the seeds of organic architecture.

Muennig’s own home on a remote spot at Partington Ridge, which he built in 1971 and where he lived for decades, truly exemplified the aims of organic, eco self-build architecture. Visitors entered it through a moon-shaped door inspired by Chinese temples that was cut into the hill. They were then confronted by — and forced to circumvent — a waterfall cascading just inside the door before walking into a living room full of banana trees and vines. This originally contained a dining table that was later inaccessible when the room became totally overgrown.

If Muennig was once part of a relatively obscure architectural subculture in the 70s, he is now highly sought-after and many his clients are wealthy entrepreneurs. One of his best-known projects is the luxury eco hotel, Post Ranch Inn, which opened in 1992, and which illustrates the wider acceptance today of environmentalism.

For Muennig, the position of his houses is paramount. Before designing Post Ranch Inn, he climbed trees to determine the best views for it, then created its tree houses crowning slender stilts, earth-sheltered, Hobbit-like rooms carpeted in grass and wild flowers and cylindrical cabins deliberately echoing the redwood trees that dot the site. Its owner and developer Mike Freed admits that convincing investors of the soundness of a hotel without right angles proved a challenge.

Muennig’s clients seem to like their homes to be located in spots as secluded as his own house. For film producer Paul Junger Witt, Muennig designed the glass and steel Witt Guesthouse, perched high above Highway 1 and reached via a perilously steep path. An early Muennig project is the turtle-shaped, $1m Psyllos House on Pfeiffer Ridge, commissioned by John Psyllos, a California-based olive producer. It was later bought by a venture capitalist and his wife who hired Muennig to design the aeroplane wing-shaped, grass-roofed, glass-walled Cooper Point house which is self-sufficient — solar panels allow it to run independently of the electricity grid. The aeroplane motif was perhaps a throwback to his early training in aeronautical engineering.

Although Muennig’s architecture embraces nature, his buildings are designed to ward off the harshest elements: "Underground houses stay at a constant temperature of 72 degrees, he has said. "Also, they’re fireproof and more protected from high winds."

Today, organic architecture has a huge following, thanks partly to Richard Olsen’s cult, 2012 book, Handmade Houses — and to a new monograph on Muennig called Mickey Muennig: Dreams and Realizations for a Living Architecture (Gibbs Smith).

Muennig’s work not only chimes with our growing environmental concerns but his bespoke buildings — which directly express his clients’ tastes — are also admired for their individuality and artistry.

Thanks to Gibbs Smith for images from Mickey Muennig: Dreams and Realizations for a Living Architecture, which is available to buy here