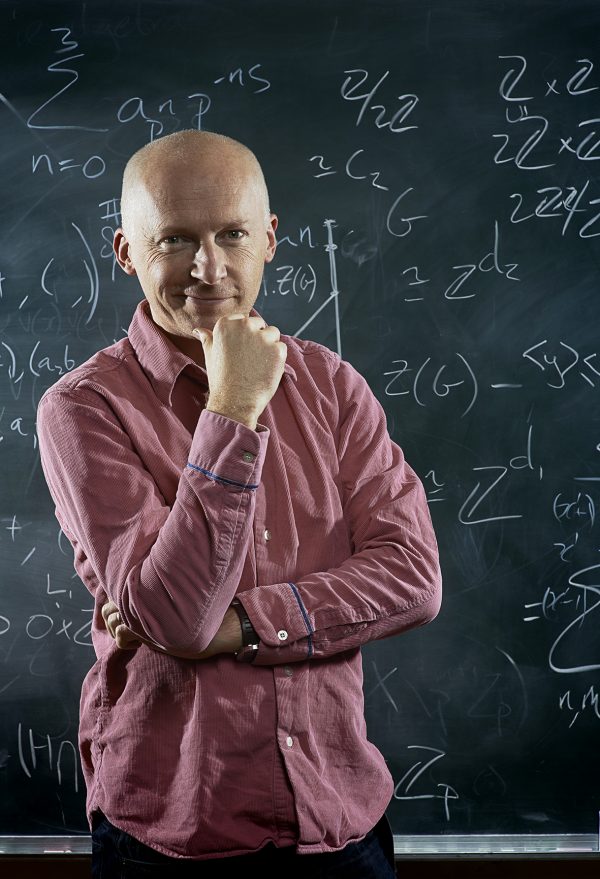

Interview: Marcus Du Sautoy’s musical journey from AI to Bach

Little Atoms catches up with the Oxford Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science ahead “Bach, the Universe and Everything” his performance with the Orchestra of the Age of the Enlightenment at King’s Place, London on 1 December

Which side of you is more drawn to Bach: the musician or the mathematician?

First of all, it was the musician in me that is drawn to Bach from a young age as a trumpeter listening to Bach's Brandenburg Concerto. I also sang in a local youth choir and we sang Bach's Magnificat. I was certainly drawn to Bach then just for the amazing emotional rush you get listening to that extraordinary music.

But as time has gone on, I've got more and more intrigued about quite how he's achieved this extraordinary music. And that's when I started to bring my more mathematical side because I knew Bach was always traditionally down as the mathematicians’ favourite composer. And sitting with scores and looking at actually how he puts the pieces together, that's when I really appreciated the extraordinary mind at work.

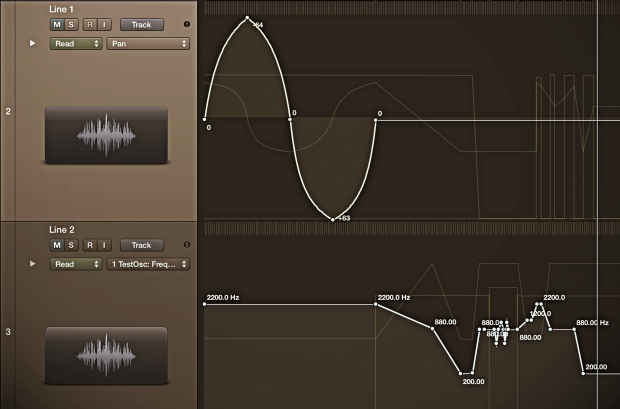

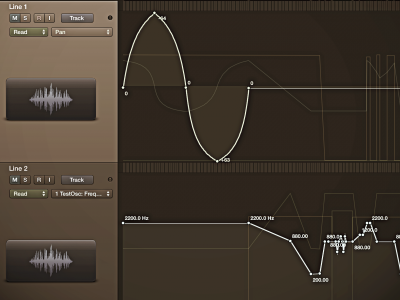

Quite often Bach is something you actually have to see visually rather than listen to, to really appreciate the structure of the thing, because you almost need to take it out of time and see it as a piece of geometry. And that's part of the appeal. The mind is trying to see the grand structure, although you're only getting this very small window on it. So the mathematical side of me came to appreciate Bach much later than the musician in me.

As you say, Bach is the mathematicians’ favourite. Why is that?

The sort of tricks that Bach uses to grow a piece from a very small cell into something hugely complex are ones that immediately a mathematician will recognise. So, for example, in the Goldberg Variations, the idea of theme and variation is to take something you then want to develop and change.

So you get a sort of seed of music and then some cryptic little notation. Like for example, you'll see one line of music. At the end you will see a clef turned upside down. And you as a musician have got to think, “OK, what is Bach asking me to do here” and then you realise, “Oh, he wants me to play the thing backwards and upside down at the same time as going forwards.'' So you have two voices which weave beautifully together. But in what Bach’s told you there's an algorithm that develops. And playing it together creates this wonderful complex sound world.

Bach was actually recognising that the universe did seem to have a sort of mathematical structure to it. So because he was trying to celebrate the creation of the universe, which he believed came from God, he recognised amazing harmony in mathematical structure. That's why you see this resonance between science and maths and the music that he's trying to write.

Previously on Little Atoms you've talked about and demonstrated the music we can find in equations and algorithms. Do you think music can communicate the kind of pattern and frequencies in maths and science in a way that words can't?

I do think that music is an extraordinary, rich, high-dimensional language which is able to capture things that words alone cannot. So it's really interesting when you try to express science and mathematics. That's what Bach was trying to do, but not what most composers are trying to do. What most composers are trying to do is to actually capture our internal emotional world. And very often they will find that words just aren't good enough to capture the complexity of what's happening in the brain.

My feeling is that in some ways, composers have latched on to an extraordinarily powerful code or language, which is translating the neuronal synaptic state of our emotional world into something on the page, dots and dashes, which when then fed through the orchestra gives us some representation of our emotional world. When you talk to many composers, they are not trying to write emotions: the emotion comes out of the structure and into their work. But they have tapped into some clever encoding, which is different to the spoken word. And with music you've got so many different parameters you can vary; you can capture structures which are much more complex than we can see visually for example.

The composer Nico Muhly suggests one could not be an egotistical composer writing liturgical church music, as Bach did, and that the romantic composers that came after Bach are conveying individual emotion, rather than conveying a higher state. I wonder if music created by A.I. is going to be more naturally geared towards an egoless music or less romantic music and more formal music.

It's interesting because you see a shift back into the 20th century, where you get a much more structural mathematical musicology appearing again, which is perhaps closer to the age of Bach. And people find that harder to get emotionally engaged in.

But even though people might feel like they're taking their ego out of that music, I just think it's inevitable that it bleeds in. I don't think that Bach has taken himself out of the equation because he's trying to write music for God.

This is what is interesting when you get to AI. You have to remember that the reason that we're having this creative AI revolution at the moment is because of the extraordinary power of machine learning to take data and to have a piece of code that can learn, change and mutate because of its interaction with that data. But because that data at the moment is primarily coming from human composition, what we're getting is AI music that is almost like a new filter or a new exploration of our human soundworld. So what you're hearing is still human music played through a new sort of instruments - AI rather than clarinets.

Instruments are interesting because they create a barrier. You’re taking the music through this kind of machine, the orchestra. Now we’re taking human music through the machine of AI.

But people occasionally feel cheated if they respond emotionally to a piece of music created by AI. I don't think they should, because they have to remember that this AI has trained on a human data set. And so it's actually tapping into understanding of the human emotional world.

What you're going to get is something quite interesting, which is more of a fusion of our collective humanity rather than an individual's human take on an interaction with the world. So although you'd think that AI music should be the most egoless, that's a mistake. And it's an important thing to recognise, because this is one of the problems with people interacting with algorithms at the moment, that we think they're very neutral and even amoral because they are a piece of mathematics. What they're not recognising is that very strong opinions are being expressed, because the AI is learning from a data set which is coming from the human. And so we think a lot of weird biases are coming into algorithms because of the bad training that is being given.

But you still get the idea that if something that is not the immediate result of say, trumpets blowing and fingering, it's somehow a less authentic form of music…

The issue of embodiment keeps arising in AI creativity. We’re starting to see things coming out of algorithms which have a complexity that’s starting to really push humans to understand. AI can deal with a level of complexity that maybe we as embodied, sensual beings just find difficult to navigate.

In music some of the pieces are so complex that our ears and brains are not able to make sense of what's going on. And we start to find it very unsettling.

I did an exercise with harpsichordist Mahan Esfahani at the Barbican when I launched my book The Creativity Code. We created a piece which was a Bach/AI hybrid, taking pieces out of one of the English suites by Bach and asking an AI to fill in parts. When we played it to the audience at the Barbican they would have to guess which parts were Bach and which were AI. They found it impossible to tell. The one person who could tell the difference was Mahan. Because he said as soon as it hit the AI, he realised: “I can't play it because of the fingerings.” It doesn’t sit under the hands in the way Bach’s music does. That was really fascinating because though it sounded like Bach to him, it didn't feel like Bach to him because Bach was writing music that he could play easily as well. That was part of his parameters.

So we may well have to put that consideration into the learning process and the restrictions of what this AI is producing. If we want to think that we as humans are going to enjoy interacting with that, we may have to give the AI some sort of artificial body where it's actually having to navigate through some sensual interaction with the environment, or else it's just going to go off on its own journey... which would be interesting in its own right.

Do you think in centuries to come we’ll revere the people who wrote the code and the algorithms in the same way we revere Bach? Or will we revere the AI?

This is fascinating because it's going to raise the question of who owns this music, and who gets the royalties. Is it the person who writes the algorithm that started learning? Or the dataset that was fed to it? Does the algorithm itself has to have some sort of legal status?

I rather like this idea that Brian Eno came up with, of us being less obsessed with the idea of genius, and of one person being responsible for a creative act. Eno suggests something that you should talk about scenius. That any creative act is always made up of many people's input.

So this new revolution might help us to question actually even some of what this is, just purely within a human context that we will recognize that we need to give credit to many different components.

I found that suddenly, for example, in my work with the theatre company Complicité, it's such a collaborative creative process that by the end you don't say the play was written by anybody. It's written by everybody.

You're going to have many people being credited with music that comes out the other end of a piece of AI.

One of them will be the person who wrote that original code that enables the thing to learn in an interesting way. But another one will be whoever created the datasets that you seed, the composers that it's learning from; and who made the choice of which bit of the data set to to give the algorithm.

It will be interesting from a legal point of view who will be credited with the music. But it reveals this whole journey that we're on, seeing AI really doing some interesting things. We shouldn't think about this as a source of competition - “is a composer going to get put out of a job by AI?” - but really as a collaboration. It will be a composer and AI working together to create something interesting and new.