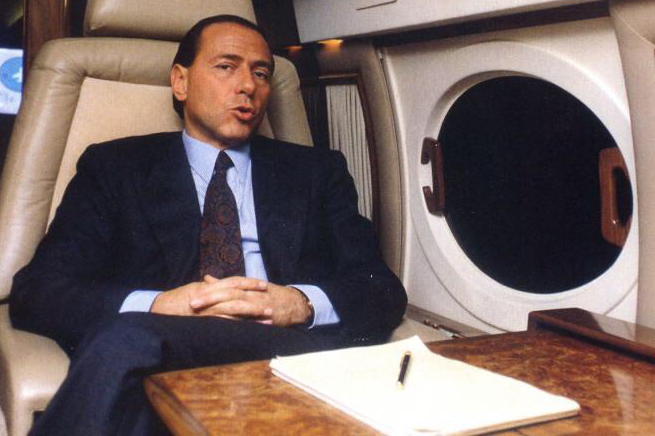

“I am absolutely convinced that [Donald] Trump will guarantee the authoritativeness and poise America requires to carry on leading the free world,” Silvio Berlusconi told the Italian media the day after Trump's shock victory in the US presidential election. An unsurprising open endorsement: Berlusconi's ambition has always been the same as Trump's, the alpha-male ultimate dream: lording it over others, at any cost.

If Trump's victory was unimaginable, so was Silvio Berlusconi's career as Italy's prime minister; not so much how he got there, as the spell he enjoyed despite having been under criminal investigation.

The Italian three-level judicial system did the rest: the extraordinary slowness of trials meant that several of the crimes Berlusconi was charged with lapsed. If you employ the best lawyers that money can buy – and Berlusconi, the son of a banker, has never been short of that – you can escape justice all too easily.

Eventually, having gone through over 20 legal proceedings, Berlusconi was sentenced for a relatively minor fiscal fraud – a smaller breach compared to many others he was never convicted for as judges simply ran out of time. On 1 August 2013, he was sentenced to four years imprisonment for tax fraud (a trial on the financial misconduct of his media empire headquarters Mediaset); he never served time but instead did community service in an old people's home.

"The Milanese magnate clamied that judges and magistrates were a communist gang"

In many ways, Italy deserved this premier; the country never dismantled the system of dubious financing of political parties. From there to the series of leaders, with suspicious motives as to why they want to be at the top, is a short step.

Nonetheless, Berlusconi's reasons became clear early on. He wanted to change the law to avoid being imprisoned. How he "stoically" endured the pressure from the judiciary perversely turned him into a victim. The Milanese magnate used to rail against the legal profession and maintained that judges and prosecuting magistrates were a Communist gang conspiring against him.

Many among the public sympathised with that: how could you not show loyalty towards the leader who trivialised the importance of paying tax so that you could pay less into the much-hated state coffers? These anti-establishment tactics have become the user's manual of every wanna-be populist chieftain, including Trump and Nigel Farage. Berlusconi's story has been carefully studied in many a political party headquarter.

Pathological narcissism plays a massive role for Trump and Berlusconi. Make no mistake: the latter would love to be in charge again, despite his age, and rub shoulders, as he used to, with the international movers and shakers. Global braggadocios and control freaks alike were always Berlusconi's best pals: from Muammar Gaddafi to Vladimir Putin, via Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and George W Bush, Berlusconi always made sure Italians were aware what brilliant company he surrounded himself with. Importance by reflection. Slyness by association. The message was straightforward and easy to deliver.

Importance by reflection. Slyness by association

Censoring dissent wasn't difficult either: José Saramago, the great Portuguese author who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1998, had all his books translated by a publishing house you could trace back to Berlusconi. Until one day Saramago submitted work depicting the tycoon as a disingenuous mafioso, a “disease” of Italy's noble blood: the only book (The Notebook) whose rights those publishers didn't buy.

Berlusconi always had it his way. As a result, Italy's already shaky standing in the world – a century old, embarrassing issue plaguing the nation's international reputation since the end of World War One – fell to an all-time low. A tragic case of punching below one's weight. Yet, how you choose your leaders is a matter of seriously underestimated importance; in Italy, at least. And it's now reached America.

Trump and Berlusconi are so similar you'd be forgiven for not finding any differences. Looking closely, however, you can spot a few. Scrape away the common tinted foundation made up of hardened male chauvinism, the coiffured look and a penchant for lying through one's teeth, you can perhaps see this: Trump now has to deal with a multi-racial nation that will put up a huge fight the scale of which Berlusconi has never had to confront. A difference of sheer demographic disparities, as Italy is only now becoming slightly less white.

Can the trajectory of the disgraced Italian prime minister tell us anything else about Trump? In my opinion, we can draw three further conclusions: a) absurdly rich men, like those making it to the top of Forbes list, should be barred from entering any public office – their persona has occupied enough public space; b) political parties and campaigns shouldn't be financed by wealthy investors (utopian, I know) – private money tends to mix badly with public interests; and, most importantly, c) once you've allowed characters like Trump and Berlusconi to rule, it takes years to counteract their claim to anti-establishment hero status (Berlusconi was first elected immediately after Italy's early 1990s corruption scandals and portrayed himself as a refreshing "new" face) – even though they were spawned by the very establishment they like to disavow. A true paradox.

As strange as it may seem, untangling the anti-establishment discourse right-wing populists peddle is precisely what progressives need to focus on – and fast. Time is running out: the quick demise of Labour, SPD (Germany), PSOE (Spain), the Socialist party in France and the humongous rift in Italy's Democratic party – all EU parliamentary allies of Jeremy Corbyn and company, though not for long – are alarming signs of the darker days lying ahead.