Beware the Prolier-than-thou style

Politicians and pundits alike revel in portraying prejudice and ignorance as essentially working-class values

This article originally appeared in issue 2 of the Little Atoms magazine. To find similar articles and buy a copy, please click here.

The open invocation of class by politicians may have declined since the 1980s, but it is there in the background of any discussion of British public life, like the drone of heavy traffic near a motorway. When I began researching my recent book on meritocracy I anticipated that I would find ample evidence of Britain’s status as a class-ridden society. Yet such was the scale of ingrained privilege that by the end of my immersion in the social mobility oeuvre I half-expected all doors to publication to be sealed off due to my not possessing the appropriate Norman Conquest surname.

Yet most of us recognise that Britain is a society without equality of opportunity between the classes. Where class analysis has melted away is on the cultural side of things. Culture is no longer considered a product of economic conditions, but is instead treated as an organic and largely autonomous phenomenon almost devoid of political significance. The study of culture has been firmly decoupled from the study of economics. A fad for “authenticity” emanates from university campuses and fans out across the land. At home it seeks to avoid being “judgmental”, and abroad it can at times crudely romanticise the more barbaric aspects of non-western cultures.

The fissure between those who treat culture phenomena in isolation – versus those who view it as (at least in part) a product of the economic structure of society – has long existed on the left. In the past some socialists and liberals were apt to romanticise the working class uncritically. Others, such as the working-class scholar Richard Hoggart, recognised that cultural life was to some extent formed by the work people did. As Hoggart put it in his seminal book The Uses of Literacy: the working class did not inhabit “conditions which produce measured tones or the more padded conversational allowances”. The masses were not necessarily ignorant out of choice, but as a result of a system of production which facilitated ignorance as well as an abundance of material goods. The coarseness of working-class life was not something to apologise for or celebrate; rather it was a reflection of the brutal and unforgiving nature of machine civilisation. Importantly, it was something to be overcome. Culture should not, as right-wing elitists like T S Eliot maintained, be a pursuit with which only a minority could ever engage. However, distinctions and value-judgments were possible and even desirable.

Socialism was about improving yourself as much as improving society

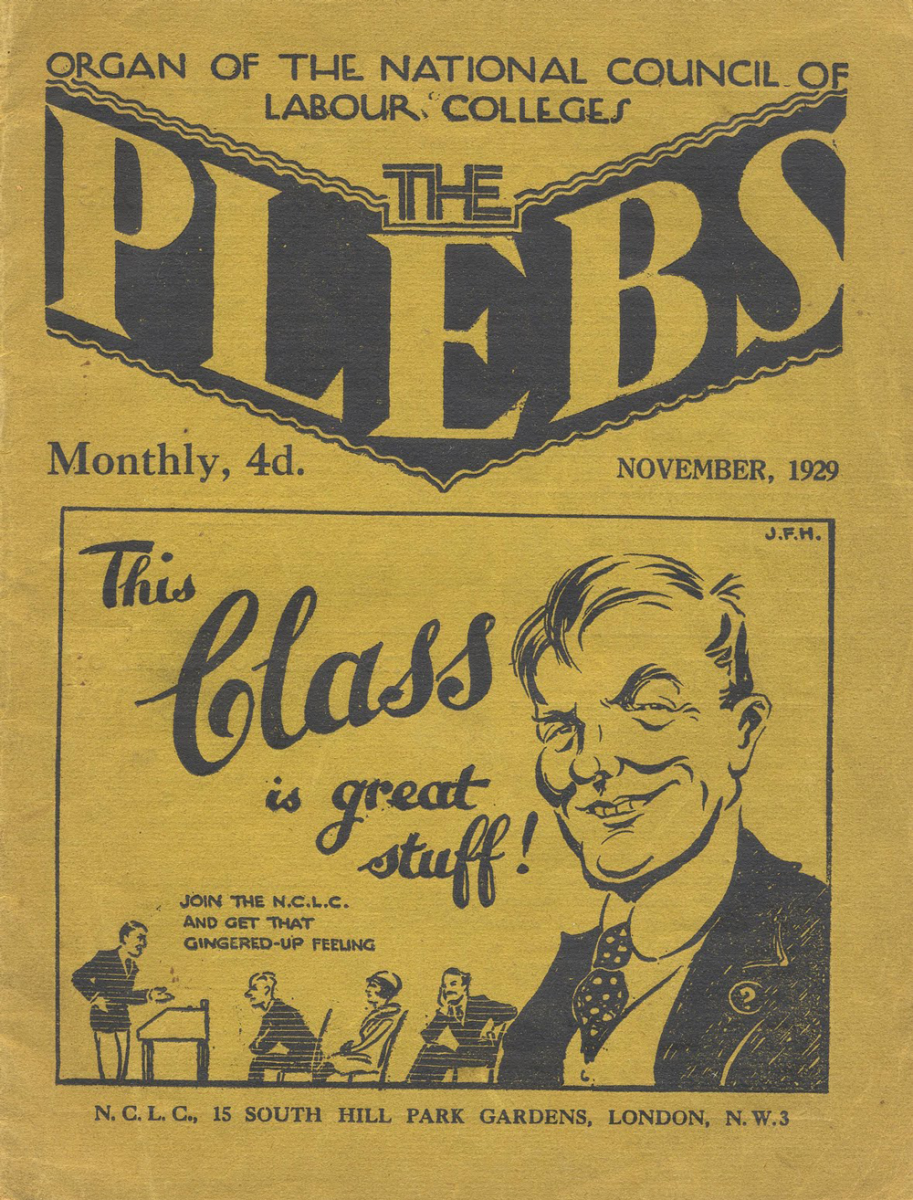

This chimed with what you might call an elitist doctrine of socialism. Notwithstanding the fringe eugenicists who wanted to go much further – “building up our nation with folks of sound heredity”, in the words of the American novelist Jack London – a levelling-up of working-class culture was considered a central plank of socialism. This led in 1908 to the creation of the Working Class Self-Education Movement, otherwise known as the League of the Plebs. For communists the idea was encapsulated by Leon Trotsky’s prophecy that, come the victory of the world revolution, “the average human will rise to the level of an Aristotle, a Goethe, a Marx”. For democratic socialists in the 20th century, there was the working men’s club movement, which offered a variety of self-improvement opportunities to members, such as lectures and keep fit classes. Socialism was about improving yourself as much as improving society.

This debate rumbles on today in some of the more distant vestiges of the left; though the relativist wing appears to have triumphed for the time being. For many progressives, being “judgmental” of anyone lower down the ladder is on a par with being a gun-toting master of the Warwickshire hunt.

But it is on the resurgent populist right where the fad for authenticity is having the more discernible political impact. Mainstream populists have adopted a technique of lionising the basest instincts of the working class in the same fashion that the quaintest aspects of proletarian life were romanticised by the most naïve of 20th-century socialists. Whereas the leftists of the past celebrated the best of the working class (often lazily and unrealistically), the populist right holds up the worst facets of working-class culture as both representative of the whole and beyond reproach as a consequence of its ordinariness.

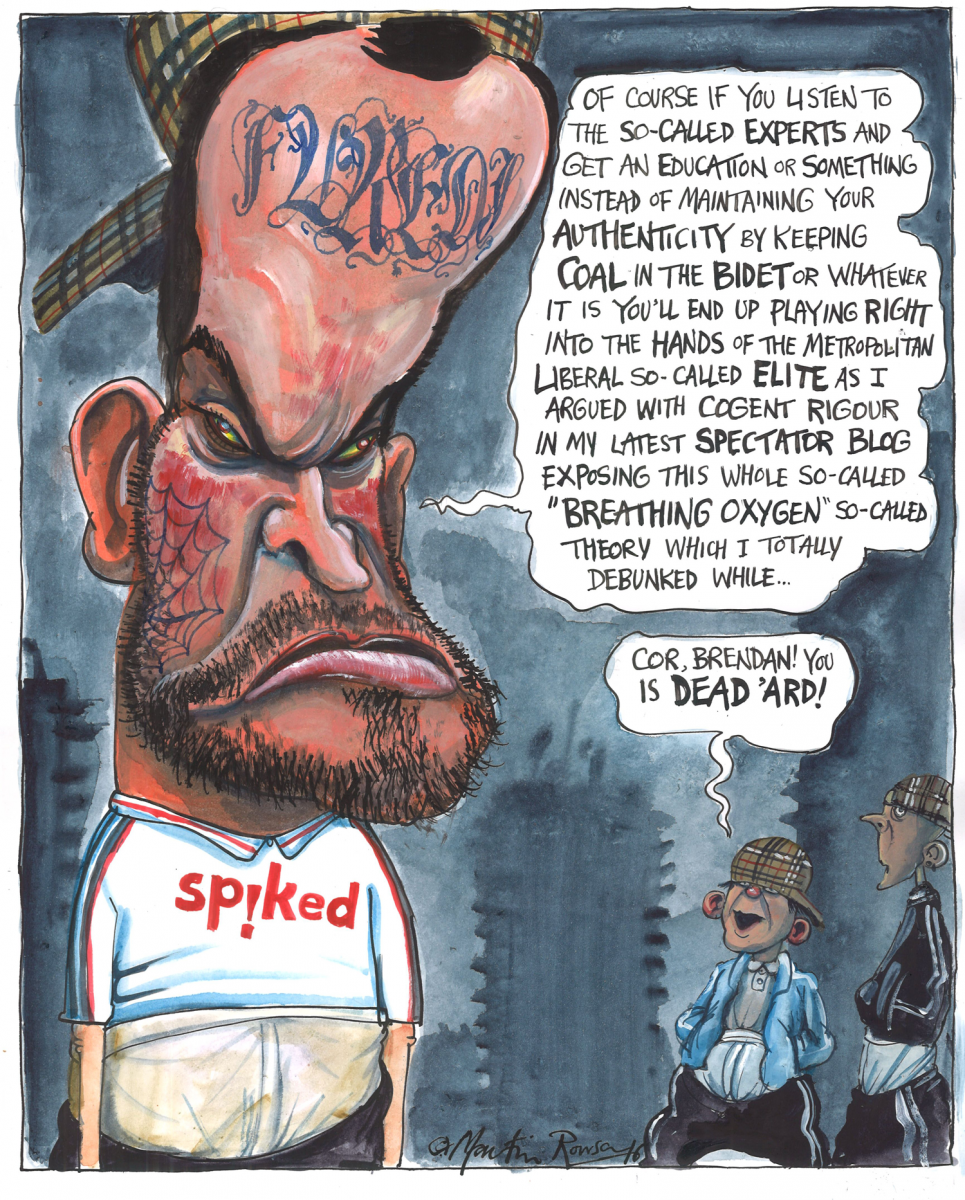

This was a pronounced strand in the campaign for Brexit and features heavily in most pieces of apologia for the American presidential campaign of Donald Trump. Thus Brexit was a “victory against big business … against big politics”, the UKIP leader Nigel Farage told reporters on the Friday morning of the Brexit result. Similarly, in a recent article on Trump, the Conservative MEP Daniel Hannan blamed the demagogue’s rise on “snobbish elites” who “disdain the people”. Meanwhile, Spiked’s deputy editor Tom Slater has written of “the elite’s fear of the Brexit blob”. “Scratch the surface,” Slater warned, “and the same fear of the braying, blokey Brexiteers lurks.”

There is a mountain of stuff like this: a new generation of pundits and populist politicians are donning figurative cloth caps every time they sit down at a keyboard or stand behind a lectern. The trend is in fact best epitomised in print by the content churned out by Spiked, who were early pioneers of the prolier-than-thou style. Descending from the Revolutionary Communist Party and its defunct magazine Living Marxism (LM), Spiked emerged from the rubble of the Berlin Wall having swapped the ultra-left sectarianism of the RCP for the ultra-conventional doctrines of Milton Freedman and Friedrich Hayek. Never knowingly not on Radio 4, the former cadres of the RCP pride themselves on being loose-cannon dissenters with a bulging book of social contacts. Shaking off much of their former communist ideology like an old coat, what the remnants of the RCP did retain was a belief that omelettes (whether capitalist or communist) require half a box of broken eggs. Capitalism should be defended, as the editor of Spiked and self-proclaimed Marxist Brendan O’Neill wrote in 2007. Those crushed underfoot should presumably quit being Luddites (a favoured prolier-than-thou term) and rejoice.

Crucially, rather than being suspicious of working-class ignorance – which after all is not a judgment on the working class itself but on the material conditions which produce such ignorance – the prolier-than-thou populist trips over himself to express sympathy and solidarity with the white working class, based on the notion that the latter supposedly reject the values of a la-di-da metropolitan liberal elite. The newly discovered working man is of rhetorical value, but only so long as he sits at home swilling lager and sticking two fingers up at “political correctness”. The sense of a rhetorical con-trick is heightened by the fact that the same commentators show scant regard for supposed working-class values when those values pose any kind of threat to the economic power of Britain’s genuine elite (i.e. through strikes and protests against those who possess all the money and property).

Of course, as with most political arguments, there is an element of truth to the complaints emitted in the prolier-than-thou style. Europe is run by a distant elite and not all grumbles about immigration are code for economics. Living in a place where fewer and fewer people speak English can feel as deracinating and discombobulating as being a migrant yourself. The displacement of class in left-wing discourse by indicators of identity very often drips with contempt for the “always wretched and complaining classes”, as Yasmin Alibhai-Brown sneeringly referred to the white working class back in 2009. This is no more than conventional class hatred re-distilled in contemporary bottles: why can’t the useless indigenous working class keep up with plucky entrepreneurial newcomers?

However, one needn’t adopt a snobbish or dismissive attitude to recognise that working-class people can at times be manipulated by vested interests. Raising this objection with the prolier-than-thou populist is liable to result in accusations of snobbery being flung at you like a handful of wet sand. “Ah, he believes they’re victims of false consciousness; he thinks they need superior types like him to tell them what to do.” Yet there is ample evidence to suggest that a working-class audience is capable of being manipulated by demagogues. People do occasionally act against their own interests, as is evidenced in other circumstances by the women trotted out to defend religious obscurantism and the Jews who can always be found to make excuses for the latest antisemitic utterance of a fat Middle Eastern cleric. As Ipsos-MORI documented prior to the June EU referendum, the public had accepted “a number of significant misperceptions about the EU and how it affects life in the UK”. This included massively overstating the number of EU immigrants in Britain as well as grossly underestimating the number of worker-friendly laws emanating from Europe. At the risk of sounding like a cosmopolitan bourgeois liberal sneering at the “Brexiteer blob”, I suspect that decades of crude anti-Europe propaganda from the tabloids may have helped form the attitudes of at least some of the people who lack the time (economics again) and the expertise (yes it does exist) to delve into byzantine EU policy papers.

Demagoguery couched in ordinariness finds a ready audience

To digress for a moment, I grew up in a part of Somerset where it isn’t unusual even today to hear jokes about “Pakis” and “queers” in the pubs and clubs. It is bred of ignorance as well as a fearful economic precarity. The two things often mix, producing a reactionary soup of resentment directed at any group suspected of doing slightly better than you or of getting an “easy ride”. As a teenager I rebelled against this ultra-reactionary mentality in about the least rebellious fashion imaginable – by joining the local library and reading omnivorously. Education seemed at the time like the antithesis of the obnoxious local posture of sticking two fingers up at the establishment, which tended to mean running down foreigners. My rebellion didn’t necessitate sneering at the people who believed in that sort of thing. Nor did it involve making excuses for them. But it did mean identifying claptrap in as clear-eyed a fashion as possible. And it was pernicious claptrap, however “authentic” or “blokey” it might have sounded to the fair-weather friends of the working class in SW1.

At bottom, the prolier-than-thou style is a tactical manoeuvre. It is a method of political persuasion rather than a genuine concern for how the working classes live. Aristotle originated three terms to describe the rhetoric of political persuasion: ethos, pathos and logos. All three are of interest to this debate, especially the apparent triumph of pathos (the appeal to emotions) over logos (facts and figures) during the Brexit vote. But particularly interesting in this case is the use of ethos. The appeal of character – or more specifically, of exceptional characteristics – has traditionally been a way for a politician or speaker to gain an audience’s assent. A speaker who possessed ethos was a superior sort of person, able to gain the audience’s trust by sheer force of personality – not necessarily charisma, but through the values he or she embodied: expertise, good sense and fortitude.

A fad for authenticity emanates from university campuses

This, again, has been turned on its head by the new populists: the politician or pundit of today persuades by posing as ordinary. The doctrine of ethos has been inverted so that being unexceptional or even ignorant is considered a sign of trustworthiness. Expertise is profoundly suspect. Added to the mix is an English distrustfulness of the flouting of talent or superiority in a way that is more easily accepted in a place like the United States. To think a lot of yourself is to court ridicule, especially with a working-class audience. To take yourself too seriously is ultimately to impugn your seriousness. There is an egalitarian edge to this – “we’re all equal at the end of the day” - but it is also the distant echo of a hidebound acceptance of class stratification: if a person is thought to be getting above his station he is quickly pushed back down into his box like a stake driven into sodden ground.

Demagoguery that couches itself in ordinariness is thus able to find a ready audience, especially if it is able to summon the half-imaginary expert bolted in his ivory tower with a violent sneer plastered across his face. But it is a very anaemic sort of rebellion. It is “more democracy”, but only in the sense that a painting from the Museum of Bad Art is a Rembrandt or a Picasso. The weak are no longer to pilfer the pockets of the rich. That would mark them down as virtue-signalling luddites. The real enemies of the working class, the prolier-than-thou pundit or politician protests, are the frightful elitists who want to regulate the bosses – the captains of industry who, free from the shackles of regulation, would like nothing more than to shower the lower orders with cash and goodwill. In true prolier-than-thou style, they egg the workers on to take back control, not by storming the Bastille, but by defecating in their own front garden. Just don’t expect them to clean up the mess when closing the door fails to mask the smell.

Buy Little Atoms issue 1 and 2 together for £15