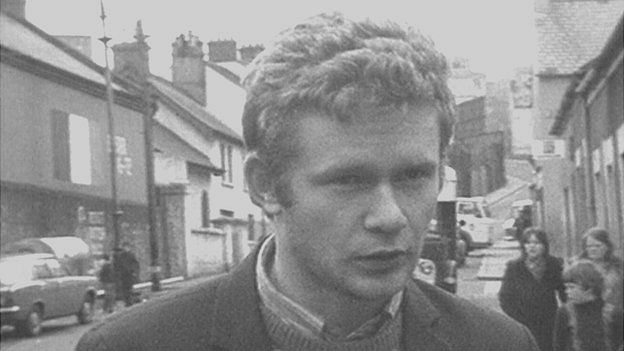

Martin McGuinness saw peace as a tactic: we may be lucky he succeeded

Northern republicanism is in a stronger position than ever

In the early 2000s, a few years into the post Good-Friday Agreement Peace Process, a friend and I waited outside London’s School of Oriental and African Studies, waiting for Martin McGuinness to arrive. McGuinness was due to speak that day. It was a beautiful summer evening and we were keen not to take our seats in the windowless lecture theatre until we absolutely had to.

McGuinness’s entourage arrived, in the de rigeur black 4x4 with tinted windows. As the Sinn Féin man and his people stepped from their vehicles, a small group of skinheads – probably National Front – emerged seemingly from nowhere, waving Union Flags, Sieg-Heiling, and chanting “IRA: murdering scum!”

McGuinness glanced over quizzically. Police moved quickly to cordon the neo-Nazis. As they did so, McGuinness walked towards the chanting skinheads, cocked his head, and said, simply, audibly: “Go on home to your Ma’s”, before striding into the lecture theatre.

The message was pretty clear: the petty thugs of the National Front were out of their depth confronting senior members of the IRA.

This was a long way from Chuckle Brother deputy first minister Martin, telling the press about his love for English cricket, and generally laughing his way round Stormont with that other old bruiser Ian Paisley like two old men who’d forgot what all the fuss was about.

In later years, McGuinness clearly enjoyed political office and its trappings, and was probably, to a certain point, relieved that the shooting was largely over. Does that mean he was a “man of peace” as some will rush to paint him?

It depends how absolute you want your commitment to non-violence to be: the Provisional IRA’s embrace of Northern Ireland’s curious form of parliamentary democracy has always been tactical rather than principled. By the mid-90s, physical force republicanism was at a dead end. The occasional bomb or bomb scare was not making any difference to the political landscape: the UUP and SDLP, with the support of the Reynolds and Major governments in Dublin and London, were attempting to forge a peace process (which would eventually have to involve Sinn Féin and the DUP); perhaps most relevant, given the mess these islands find themselves in now, the customs border between north and south had been abolished, post-Maastricht.

The IRA was thoroughly infiltrated by informants (with some diehard republicans even muttering darkly about McGuinness himself), to the point where it was barely operable. In these conditions, it made sense to move increasingly away from the Armalite and towards the ballot box.

But that does not mean that McGuinness and Adams did not make some tough choices: their generation had cast themselves as the keepers of the flame of physical force republicanism, after the Official IRA was deemed to have been weak in the face of loyalist attacks on nationalist communities in the late 60s. (The leadership of the Officials had moved to an increasingly left wing position which was at odds with the Catholic nationalist tradition from which McGuinness started. They would dismiss McGuinness and other provisionals as the “rosary bead brigade”.)

To declare that politics was the way forward was a risk, and if we’re to be honest, one that only someone with McGuinness and Adams’ standing with the IRA could have taken.

And it’s a risk that has paid off: the recent Stormont election, called after McGuinness stepped down due to ill health amid the “cash for ash” fiasco, has left republicans in a stronger position in the north than ever before, with the effective end of the Unionist veto in Stormont signalling a new political reality for the six counties. Into this consideration we must factor the tactical stupidity of the DUP's Arlene Foster in her party's backing of Brexit, her arrogance over the Renewable Heat Incentive scandal, which saw millions of pounds of government money misspent, and the idiotic baiting of the nationalist population over Irish language issues (falling straight into a carefully-laid Sinn Féin trap). Arlene's diffficulty is Ireland's opportunity.

In the south, too, Sinn Féin is in a stronger position than ever before. At some point (unlikely to be the coming election, but perhaps the next), a mainstream party will form a coalition with Sinn Féin. We will then face the prospect of the same party in government north and south of the border: Sinn Féin will say this in itself is a case for a united Ireland with a Sinn Féin government.

In this last configuration, the death of McGuinness will be of advantage to Sinn Féin’s southern command. Much of the middle class in the republic remain suspicious, even fearful, of the hard men from Belfast, Derry and the borders who have led Sinn Féin thus far. A young, post-Troubles, southern-led Sinn Féin, with a broadly left-populist platform, will find favour with a new constituency once the old Northern command fade into the background.

McGuinness’s commitment was always to the Sinn Féin/IRA cause. In this context, his career was a success. It is merely fortunate for the rest of us that in the end, the Derry hard man found his success through democratic politics.