How long does a warning last?

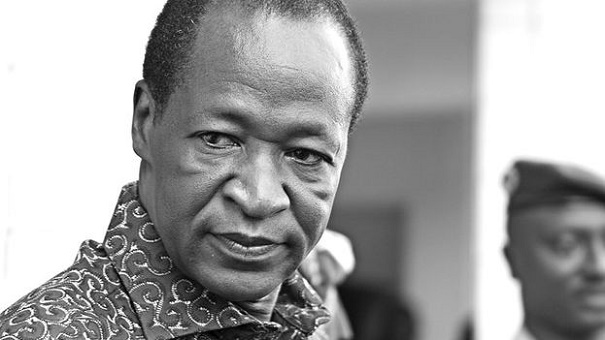

Last October Blaise Compaoré’s 27-year reign over Burkina Faso was brought to an abrupt and unexpected end. One of Africa’s most redoubted strongman rulers saw his authority evaporate in just three days as people power swept through Ouagadougou.

The spark for the uprising was a special session of the national assembly, summoned to amend the constitution to let the president run for yet another term in office.

This was just too much for the huge crowds who poured into the streets to express their anger and set fire to the parliament, forcing members to abandon the vote. Soldiers were not prepared to use force against the demonstrators – and before the week was out “Beau Blaise” was gone, his speeding convoy of SUVs caught on a villager’s camera phone, heading south towards the border and into exile.

There was a flutter of foreign media coverage. But within days the story of Compaoré’s downfall – a not very violent event in a small and poor country – had slipped off the Western radar screen.

Yet across Africa, and particularly in the Francophone half of the continent, last October’s events in Ouagadougou have not been forgotten.

For tolerance is fading for old-style perpetual presidents, reconfirmed in office through manipulated elections every four or five years. Fewer and fewer sub-Saharan citizens are prepared to endure endless rule by “Big Men” who regard power as a lifetime sinecure.

The change in attitudes is particularly evident in cities, where the expansion of schooling and access to the internet and international news channels such as France24 has forged a widespread public awareness of events and trends worldwide and, especially, across Africa.

International commentators sometimes wonder whether the “Arab Spring” will spread south of the Sahara. That’s the wrong question. Sub-Saharan Africans got there first – in the early 1990s.

Authoritarian single-party regimes were toppled, one after another. And when elements of the Malian security forces loyal to the dictator Moussa Traoré shot dead protesting schoolchildren, the paratroop unit intervened to arrest the president and invite his opponents to establish a democracy.

So for the past 25 years, many – though not all – sub-Saharan countries have been governed by multi-party political systems with regular elections.

However, the reality has not always lived up to the constitutional theory.

In countries such as Ghana, Benin, Niger, Sierra Leone and Senegal, or Kenya, Zambia and Malawi, power has changed hands at the ballot box. In Nigeria, the continent’s most populous nation, freedom of speech and association is now fairly well established.

However, there are also many states where democratic structures exist in formal terms but are in fact inhabited by regimes who manipulate the rules to maintain their power and privilege.

Old-style intolerant dictatorships, squeezing dissent and forcing opponents into jail or exile, are no longer the norm. These days most African presidents are at least nominal democrats - submitting themselves to the voters’ verdict every few years.

But some are reluctant to comply with the term limits that were so breezily accepted when multi-party politics was first imposed a decade or two ago.

The temptation to tinker, dispensing presidential patronage to persuade parliamentarians to relax the rules, often proves too much – even in countries that in many respects are plural and democratic, with a range of parties, a lively parliament and free media. Rulers often come under pressure from their protégés and business backers to find a way to stay in power and keep the gravy train running.

And among the public this fosters disillusion with politics, as citizens conclude there’s not much point in voting at all if it will change nothing and they’ll be stuck with the same old, same old…because the election and campaign is manipulated or the final result is rigged.

Yet gradually, Africa is experiencing a second democratic revolution, which infuses new vigour into the formal multi-party structures that are now two decades old.

In April 2011, President Laurent Gbagbo of Côte d’Ivoire was hauled before the cameras by the opposition troops who had captured him after he had refused to recognise his election defeat and tried in vain to cling to power by force instead. Even in Burundi, 3,000 miles away in the east of the continent, jubilant TV viewers cheered on as news of his capture spread.

Sometimes parliaments block the scrapping of term limits. But the pressure of public opinion is increasingly making itself felt.

When Senegal’s veteran President Abdoulaye Wade leaned on judges to remove the bar to seeking a third term, citizens resorted to their power as electors and threw him out anyway, in the subsequent election, in 2012.

And gradually a more modern generation of leaders is coming to the fore. They see more kudos in serving out a couple of terms and then moving on to another career, often on the international diplomatic scene.

But for those still tempted to bend or change the rules and prolong their hold on power, Burkina Faso's example may give pause for thought:

Blaise Compaoré must now live out a dull life in exile, perpetually wondering whether at some point he will be forced back home and called to account for his past conduct of power – when he could have negotiated a graceful retirement, cushioned with a prestigious international appointment.