In 1983, Australia II, bankrolled by infamous businessman Alan Bond, won the America’s Cup, the world’s most prestigious sailing competition. It was the first time in the 132-year history of the race that the New York Yacht Club had been defeated. The win sparked extraordinary celebrations in Australia, and Bond declared it “the greatest victory since Gallipoli”.

The only problem is that Australia, and the Allies, were soundly defeated by young commander Kemal Ataturk’s forces in the disastrous Gallipoli campaign.

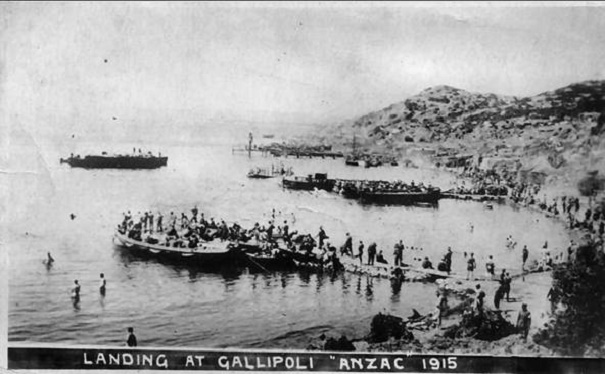

On the morning of 25 April 1915, Allied troops, mostly from the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) landed by sea at a small cove on the Gallipoli peninsula.

Churchill wanted to quickly knock the Ottomans out of the war, and Turkey had been promised to Tsar Nicholas II. In darkness, riddled by disorganisation and poor command, they attempted to wage war on an enemy perched on the perpendicular cliffs above them. The casualty figures vary wildly as they so often do with war, but it’s probable that one thousand Anz troops, mostly Australian, were killed on the first day, with a similar number wounded. The only real success of the Allies’ campaign was their retreat eight months later.

The tide of opinion of the campaign in Britain and Australia is said to have been changed by an 8,000 word letter written in September 1915 by the young Australian war correspondent Keith Murdoch – father of Rupert – under the tutelage of famous British war correspondent Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett. The letter was intended for Australian Prime Minister Andrew Fisher, but was seized upon by parts of the British establishment opposed to the wider Dardanelles campaign, most notably Minister of Munitions and soon-to-be Prime Minister, David Lloyd George. Though the Gallipoli Letter, as it became known, was riddled with inaccuracies and flights of fancy, its sentiment was accurate: the campaign, under the direction of General Hamilton, was a disaster.

This weekend marks the centenary of the Allies landing on the little beach at Gallipoli, nowhere more so than in Australia, where Anzac Day, 25 April, is something of a national obsession.

First commemorated in 1916, the legend of Anzac Day has become a vehicle of identity for Australians. It is considered the birth of the nation, which had only come into being in 1901, when the six colonies joined together to get the trains running on the same gauges and keep dark-skinned people out (there were of course dark-skinned people who were “in”, but they didn’t count.) Nationalist sentiment on the road to the colonisation were usually tied to wider causes, such as workers’ rights and sectarian antagonism from back home, or the desire to be freed of it. It proffered the myth that the unpleasant beginnings made Australians inherently anti-authoritarian, that the notion of mateship was our version of the Declaration of Independence.

It is difficult to distinguish the commemoration and celebration of Anzac Day. Some, like Bond, have substituted the pageantry for history and assume that the forces fought a courageous victory. Others like to see it as a sign of an inbuilt Australian irreverency, like how we named a public swimming pool after the Prime Minister who drowned while he was in office. The history of pacifists and the bitter and polarising fight over conscription are forgotten. Along the way, these sentiments have morphed into a cultural cash-crop that it is the vanguard of Australian nationalism.

The federal government is estimated to be spending $325M (GPB £168M) on centenary commemorations – around three times the amount Britain will spend on commemorating the entire Great War. Each MP in the 150 federal electorates can access up to $125,000 (£68,000) to commemorate the centenary at a time when the government is otherwise enforcing economic austerity.

The word “Anzac” is a government monopoly, with legislation preventing commercial use of the word. Big business is astute at cashing in on the sentimentality of Anzac Day, but it is the media that finds the greatest traction from the tradition. Born of a journalist and propelled further into popular consciousness with the 1981 film Gallipoli (starring Mel Gibson), the media gorges annually in an ostentatious celebration of defeat.

“New Zealand was not so desperate for the world's approval.”

The story has it that our boys were led as cannon-fodder by posh British generals, despite the British losing some 30,000 men to our 7,000 in the course of the campaign. It feeds into the idea of the national character that loves the underdog and cuts down tall poppies. It’s a nationalism that allows Australians to look into the water at Anzac Cove and fall in love with the reflection that shines back at them. It is “Patriotic Correctness” as the late Robert Hughes would have it.

This is not to say that nationalism in and of itself is a corrupt concept - try telling that a Pole or a Ukrainian. For all the criticism of right-wing nationalism, it has gone unnoticed that Anzac Day is now equally a tool of the left. The liberal press is drowned with critiques of Anzac culture each April. Historians and writers line up to give it a whack, without bringing any new scholarship or ideas to the debate. It is disliked because, for the all of the sledging of the British high command, it is not anti-colonial nationalism but spirited chauvinism.

All nationalism is built on mythology. Australia, its beginings completely devoid of romanticism, was compelled to search for something binding. Historian John Hirst believes “the convict stain” began the Anzac obsession. “No one ever said that the New Zealand nation was born at Gallipoli,” he writes. “New Zealand was not so desperate for the world's approval.”

Australians have barely known war on home soil. The frontier wars have been smoothed over as a wrinkle of history. The fact that post-colonial Australia has been untouched by war on its soil - and the prosperity and cohesion that has brought - is not celebrated. (Amusingly, the only post-colonial battles fought on Australian soil were The Great Emu War in the 1930s, where the army went in with machine guns against a pack of wild emus and lost – twice – and the Battle of Brisbane, where Australian soldiers, aggrieved that the visiting American troops were getting all the girls, waged battle for two nights until order was restored.) Despite vigorous attempts to change tack, the existential threats the Japanese posed in WWII do not receive anywhere near the amount of recognition. A recent addition to the debate, a 2014 book Anzac’s Long Shadow by James Brown, a former army officer who served in Afghanistan and Iraq, highlights how the funding and the reverence for the dead soldiers of Gallipoli far outweighs that for current servicemen and women.

As the Anzac legend grew following the release of Gallipoli, intellectuals became increasingly antagonised by its falsehoods. Australia’s participation in the first Iraq War in 1990, and its 2003 successor allowed the left to begin to turn back Anzac on its proponents. In recent years, it has become a parable for the dangers of following foreign empires into distant wars, giving weight to the rising mood for a foreign policy independent of the United States.

Anzac’s multiple creeds allow individuals to practice Anzac in their own way. Contention arises as much from ritual as it does from history. Commemoration and celebration are interchangeable. As one of the greatest writers on Gallipoli, Les Carlyon, noted dryly that the annual pilgrimage of young people to Gallipoli is a ceremony where “Australians murder a few slabs of beer and the New Zealanders murder a few vowels.”

There are signs that Anzac fatigue in the public is kicking in, with lower than expected ratings so far for the many television specials and dramatisations leading up to this year’s centenary. But when Anzac is so ingrained in the national psyche, it’s hard to see who is going to be the first to stop clapping.