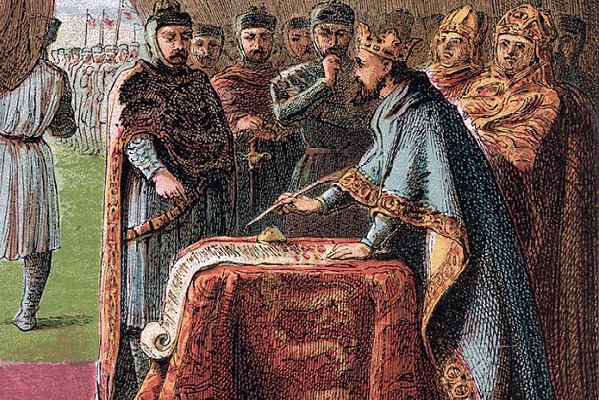

You can always stretch a metaphor too far but – as we approach the 800th anniversary – doesn’t this feel a bit like a Magna Carta Moment to you?

Broadly speaking, the Barons’ Charter of 1215 – although later finessed and reclaimed by propagandists and historians over hundreds of years – was an attempt to broker peace between the detached and self-absorbed ruling centre of the country and the disgruntled regions. John behaved as if he was above the law – the charter insisted otherwise. The charter won.

These days its significance is described as legal – the principle that no-one is above the law. Of course that isn’t true. Provision was made for members of the elite to create laws and punishments at will. In fact what the charter established was the principle that no-one is separate – above or below – the rest of society. It’s a document that applies to all – even if it applies just a little bit more to a tiny elite.

In certain respects, the country is structured in pretty much the same way as it was 800 years ago – in some cases the land is still owned by the same families.

But while the charter lead inexorably to contemporary democracy and an increasing sense of social unity, 800 years on we’re seeing this unravel.

Magna Carta's key clause is well known: "No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals. To no-one will we sell, to no-one deny or delay right or justice."

In Paisley, near Glasgow, Sharon Macaulay – who runs the Star project for people in crisis – sees arbitrary dispossession and vicious fines levied every day. “People are being sanctioned for not turning up on time for DWP appointments,” she explains. “They can lose all income for months. For people experiencing a stressful home situation, for example domestic abuse, they are highly unlikely to explain this in a public place in front of a DWP advisor. When you worry each day about survival, about feeding your family, or about a family members addiction even making it to the Job Centre is an achievement. If they can't give the truth and get sanctioned the fact they already live in poverty or have a difficult home life has just been exacerbated vastly. They need access to a computer for job searches but the library's computers are down or closed – what are they supposed to do? The majority of our people don’t have access to the Internet at home – this costs money. People in disadvantaged areas are the ones suffering the most – the statistics tell us this – and yet the general way of dealing with it seems to be to create systems which ensure they suffer a bit more. What sort of country penalises the poor for living in poverty?”

And the penalties are getting harsher. In April, the nationwide roll-out of Universal Credit began. Universal Credit has some worthy principles – it’s more flexible, for a start – but it assumes certain things. It assumes people have bank accounts and it assumes people have broadband access. You can only register online and you are mandated a specific number of hours every week to spend on the government's Universal Job Search site. Failure to do so sees benefit sanctions and penury. And yet 21 per cent of the population have no internet access at all, according to the government's own policy paper on digital inclusion published in December 2014. The DWP suggests claimants without home internet visit the library.

“I can only get to a computer in the library on Thursday evenings, Fridays and Saturday mornings,” Lisa Wright in Wigan explains. “There’s sometimes a queue so you can hang around for up to an hour. That’s the only time I can check my emails, which means if I get a sent reply to a job application on Monday I don’t see it for days. It feels like you’re constantly doing things wrong and struggling just to keep up. I met a kid last week doing 200 hours community service for robbing a shop. I’m doing 780 hours community service and my only crime is being unemployed.”

As the country races towards increasingly digitised election campaigns where online petitions and Twitter storms can influence government policy, there must also be a concern that people on the wrong side of the digital divide will be left without a voice.

Meanwhile, across the country, there’s a growing group of people who’s right to healthcare has been denied or delayed, who are exiled from the public conversation and who are constantly deprived of their standing. John Wildman, professor of health economics at Newcastle University, estimates that some 20 per cent of the population’s health needs are ignored and unknown.

“We decide on our health budget priorities based on the reasons people visit their GP and surveys of patients. But people at the lower end of the distribution curve – on big housing estates in the north east, for instance – don’t take part in surveys and they don’t go into GP surgeries so they are effectively completely unreported,” he explains.

“There’s a mixture of reasons,” according to Eileen Debaney at the Citizens Advice Bureau in Speke, Liverpool. “Some people only have pay-as-you-go phones – if they run out of money, they can’t make calls. They have to wait until the community centre is open at 9.30am to use the phone, by which time it’s too late to book a doctor's appointment. Or they feel embarrassed to fill out the free prescription form and prefer to get help from friends who don’t judge them as scroungers. It’s just horrific. We’ve had people in here and as soon as you look at them you go, ‘Jesus, they should be in hospital,’ never mind being forced on to the work programme.”

And there’s a further denial of standing in the rise of prejudice against those struggling to make ends meet. In 2013 Michael Gove said families who become so poor they are forced to turn to food banks, or who find themselves unable to buy essentials, including food and school uniforms have themselves to blame for being unable "to manage their finances".

In Rotherham, 1,400 working class girls were savagely raped and abused for years because when they reported the assaults, as survivor Sarah xx explains “a lot of people ignored us. We told social workers and police but they ignored us. They ignored my Mum, they ignored other families because we just got cast off as white trash prostitutes and out of control children.”

In 2006, Professor Pat Cantrill published a report on David Askew and Sarah Whittaker, a Sheffield couple who locked their starving children in excrement-smeared bedrooms while they spent benefit money on drink, state-of-the-art TV and computer games. It blamed low expectations by care workers. These low expectations, this idea that the couple weren’t quite as good at being parents as people with professional qualifications, allowed police, teachers and social workers to ignore a situation where maggots filled the nappy of a one-year old child who was only rescued hours from death.

Of course, a couple chomping take away pizza whilst shushing the kids so they can watch a DVD is not the tasteful face of deprivation. There is no Road To Wigan Pier nobility in such suffering. We want loneliness and despair to echo with a certain Victorian romance. We don’t want to help someone who’s a mere "chav”. These people eat too much and watch TV. They ought to know better. They should do something about it. They are the undeserving poor.

Where do you put finite resources? Well, you have a list. Some things are at the top and some things are at the bottom. There is the notion that smokers bring it on themselves, so perhaps we shouldn’t spend quite so much money on treating them. George Best’s doctor wished we could predict if an alcoholic would relapse before deciding to spend good cash on their liver transplant. At the core is the nagging idea that some people, basically, deserve to die.

But then, it’s not easy to stand next to an ugly, overweight 42-year old man – a man who probably smells a little funny – and ask the public to care enough to save him. There’s no glamour in the hacking cough of a bad tempered alcoholic and no glory in placing your arms around a vicious junkie who pretends to be homeless. Jamie Oliver’s ratings won’t peak if he tries to improve the diet of a fat man living on tinned food and super strength lager.

If you can judge a society by the way it treats its most vulnerable, what can you say about one that would prefer not to notice them, that sees the vulnerable as somebody else’s problem? Of course, as Magna Carta proves, if people aren’t being listened to, they don’t sit waiting to be heard.

In August last year I sat on a pub bench in Edinburgh while radical Scots nationalists debated how to build a modern social democracy from the ground up. The referendum was lost but their plans survived. In Manchester they’re creating a city state to fend of a careless world. In Paisley people are building an unlicensed healthcare system, swapping unfinished courses of sedatives, anti-depressants, beta-blockers and antibiotics or resorting to DIY dentistry. People are quitting this nation quietly, setting up their own support networks and looking after each other based on geography.

If these regional factions band together – if they marched on London and held their swords to the throats of government – what clauses would they put in a new Magna Carta?