"David Cameron's very punchable, isn't he?"

As his adaptation of The Trial opens at the Young Vic, playwright and polymath Nick Gill talks politics, privilege, creativity and Kafka

As his adaptation of The Trial opens at the Young Vic, playwright and polymath Nick Gill talks politics, privilege, creativity and Kafka

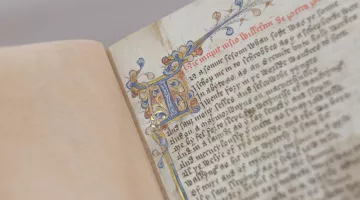

Writing, declared Kafka in his diary, is “a joke and a despair”, his own writings “helpless”. The latest adapter of Kafka’s work for the stage (his version of The Trial is on at London's Young Vic from 19 June to 22 August), the enviably polymath playwright, musician and letterpress printer Nick Gill, revels in the linguistic joke to the point of despair, the absurdist possibilities of stretching words and meaning.

His most recently staged original play, beneverunerstoost, is a freewheeling satire of how politicians use language to confuse, seduce and deceive in that most contrived of formats, the modern political speech. After a long period of gestation, Gill was delighted that the Royal Court put on a rehearsed reading on May 6th among a slew of other pre-election dramas reflecting disillusionment with the politics of the Coalition. Yet hours later, reality dealt a – dare we say Kafkaesque - twist with the 10pm exit poll and the eventual result, leaving Gill reflecting he had been “howling into a pointless void”.

The play “started out with hating David Cameron as all sorts of good things do"; a mash-up of the PM’s January 2012 speech on popular capitalism with some lines directly cut and pasted, others fed through a computer program called Emacs that looked for certain word patterns (One you designed Nick? “No, no, I wish I could. I do very, very basic programming”).

For sake of balance, the latest version of the script also drew from speeches by Nick Clegg and Ed Miliband. The result is a “Dadaist” wordscape of slogans with various phrases on loop, including; “an active government with its sleeves rolled up; these are difficult times; this government is a determined government… an effective government… a needed government… the people’s government… an universal government… ”.

At times a narrative about “Ella” cuts in – both Cameron and Miliband apparently namechecked an Ella in Bill Clinton-style storytelling sections of speeches. As the play goes on, the language and message fall into greater incoherence, the repetition and bleak dystopia evoked chiming with Gill’s breakthrough 2007 Amnesty Protect The Human Award-nominated fiji land.

Monkeys and typewriters

There was a bit of a "monkeys at a typewriter" principle behind the project: “I tried to avoid the temptation to leave a word out to make it sound better”, Gill says. He is sceptical about sculptors who say that they look at a block of marble and see something in there. He has spoken previously of his admiration of George Perec’s novel A Void, which never uses the letter “e”, and how he positively embraces the restrictions of dramatic form: “Theatre has massive limitations and if you’re not playing with those, it seems a bit silly”.

He wanted to keep beneverunerstoost’s performance open: the Royal Court’s version had a line-up of two female and three male actors at reading stands, the diversity of their appearance and delivery underlining both the comedy and the monstrousness of the soundbites.

For Gill, who demurs that he knows “a lot more about language than about politics”, torturing meaning is a cardinal political sin: “trying to pull one over on you by using a flabby word”. There’s the intention to “let people fill in the gaps”.

David Cameron’s claim in his victory speech in Witney that his re-election was a “positive reaction to a positive campaign” made Gill “feel a little sick, given that it was a campaign based around scaremongering, ad hominem attacks, and appealing to everyone's most selfish interests”.

When pressed on concrete examples of this slipperiness in areas of policy, Gill picks out Cameron’s campaign claim to have created 1,000 jobs a day. “Did people want those jobs? Were they part-time or full-time? [How much is this] claiming credit for something where you happened to be there at the time?”

He fears a self-justifying, scorched earth approach to furthering privatisation: “It's as if they're saying 'You can't trust the government to run all these public services. I mean, look at us: we're a bunch of self-interested pricks'. They're proving their own point, in a horrible, möbius strip of a government.”

He doesn’t know whether the manipulative tendency in politics is getting worse. When I ask to what extent he thinks the corruption of political discourse is due to the war in Iraq, he teases me with “one sixth exactly… Everything is so tightly tied up together".

He wasn’t at the February 2003 anti-war march for a “rubbish reason – like a rehearsal”. While his conversation is laced with quirky humour and childlike wonderment, his loathing of Cameron is vividly personal: “He’s very punchable isn’t he… a horrible person”. He thinks having the “immensely privileged” in power is a bad idea. Conservative policies “seem to lack empathy, relying on profit and are ideologically driven. If you embody all of this, it makes you a psychopath”. He agrees with Douglas Adams that anyone who wants to be in power “shouldn't be allowed to be” and suggests we could have an alternative system "like employee of the month – if you're a very, very good civil servant, you get to be PM".

"It’s quite hard to stage an overtly right-wing play without seeming sarcastic"

Gill is clear where he stands in the salvos over the political leanings of theatre. “[It’s] inherently left-wing isn’t it? It’s quite hard to stage an overtly right-wing play without seeming sarcastic”.

He also anticipates the arts facing “another five years of having to justify every action on economic grounds, and… ever more shrill cries of ‘if it's any good, it should pay for itself’. I'm exhausted just thinking about it.”

Gill cut his teeth as a playwright as a member of collective The Apathists, a group who knew each other from young writers’ programmes at the Royal Court and spurred themselves to put on one play a month as a finished product in 2006-7. One of their number, Mike Bartlett, has earned renown with a succession of critically acclaimed shows including Earthquakes in London, Cock, Bull, King Charles III and, most recently, Game.

Gill is full of praise for Bartlett’s skill and for daringly pulling off with Charles III a “simultaneously weird and populist” hit.

Now Gill is getting his own spell in the limelight with the opening of his adaptation of The Trial, directed by Richard Jones, at the Young Vic with Rory Kinnear in the lead role. He decided his interpretation was not going to be “about the massive state crushing the individual – because basically [the book] isn’t”. He talks enthusiastically about US academic James Hawes’s Excavating Kafka that busts myths about the Czech author, making him a less obviously romantic figure but by the same token more interesting. Furthermore the way The Trial saw the light of day is, he thinks, a liberation to the adapter: “Some chapters are unfinished, it was never put into a definitive order by the author, and could probably have done with a decent amount of editing. There’s a lot that is elliptical, you can make it what you want”.

Gill is “staggered” by the cast and production team working on the show. Richard Jones’s directorial process and creation of vivid stage images fascinate him, while Kinnear’s combination of characteristics as someone “completely without ego, and extremely clever, makes him ideal to pick apart a) The Trial as a novel and b) the slightly odd, very subtextual, multi-register version that I've made up”. He recalls the first day of workshops last autumn – “Richard asked Rory to read the first chapter out loud, changing all the pronouns to the first person as he moved around an imaginary space. He's such an interesting performer that watching it was enormously entertaining; at that point, I thought I'd just rewrite it in the first person, get Rory to read it and collect my fee”.

Gill has enjoyed producing an adaptation but may never have attempted one if he hadn’t been commissioned. There was a meeting in an “incredibly cold room” in the Young Vic he was shown up to with nobody in it. When Jones arrived they talked about theatre-makers they admired;Gill mentioned Katie Mitchell and she obligingly walked through the door. Halfway through the conversation it became apparent that Jones had confused Gill for his fellow Apathist Duncan Macmillan; when Macmillan went for his interview Jones seemed to mistake him for Gill. To prepare to write his script Gill deliberately didn’t read Tom Basden’s recent adaptation, Joseph K; he did watch Stephen Berkoff’s version, originally produced with Webber Douglas drama students in 1970 which “feels very devised, it brings you out of it”.

What next for Gill? There are plans to develop beneverunerstoost into a show combining music and theatre but which isn’t opera. His parallel music career continues, with bands The Monroe Transfer and Fireworks Night, studio projects and his own compositions – Salt hell, based on Old English poem The Seafarer follows Grey season in a “series of ambient/drone/modern classical LPs”. He wrote the music for Kate Wasserberg’s production of Sarah Kane’s Blasted at The Other Room in Cardiff in February. All this, and he is a new father into the bargain.

What about the political landscape? Gill shares with many creatives “a sense of dread at what the Conservative party might do, now that they [have] what they perceived as a mandate” but he’s too sprightly to be simply a sourpuss. He had an “I’m Registered To Vote” profile picture up on Facebook for weeks before polling day and was actively drawn to the Greens’ “evidence-driven” policies, applauding their pre-election decision to review a “disastrous”position on copyright that shows a “willingness to say they’ve cocked up”.

We talk about society’s long-term prospects – how we’re in an age when no one person understands exactly how every element of a tool so fundamental to daily life as a mobile phone works, because the technologies it contains are the preserve of specialists: nothing to fret about, Gill suggests, “as long as we all get along”. Would it help if politicians themselves were polymaths, not as so often apparatchiks? “It’s important to know what you can’t do,” says Gill dryly, ever-modest.