O’Connell Street, Dublin. Easter 2016.

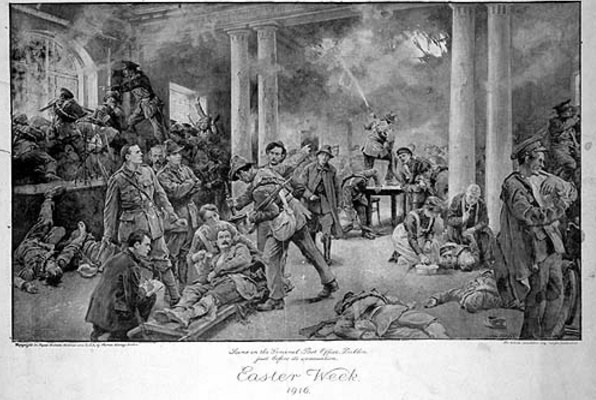

Across from the General Post Office, where one hundred years ago, Padraig Pearse, Big Jim Connolly and Michael “the Cork fellow” Collins made their stand for freedom, the Ann Summers sex shop is doing brisk business, selling Rising-themed smut, a garrison of the new empire of neoliberal sex and consumerism.

“Was it for this”, as Yeats asked?

If one was to build a time machine, go back to Easter 1916, pick up the seven signatories of the proclamation of the Irish republic – probably after they surrendered but before they were executed – take them to the Ireland of 2016, and then drop them back to 1916 in time for their executions (which transformed working class Dublin’s view of the rebels), how would they feel?

Confused? Almost certainly.

Would they recognise modern Dublin, that city of contrasts? Of fine dining and ghost estates, of gleaming new “LUAS” trams and children on horseback, of professional rugby players with over-conspicuous cars parking next to homeless people, of myriad other things that I have decided to juxtapose for the purposes of this article.

But could modern Ireland – “Ireland 2.0” – as I have begun to call it, ever have matched the vivid dreams of these faces, preserved in time?

For dreamers they were. Pearse, the kindly schoolmaster who taught his pupils the legends of old Ireland, Cu-chulainn tied to a tree, the giant Fioghann Magchughuail, the Mystic Knights of Tir Na Nog.

Connolly, the visionary socialist, who like Wilde before him, was looking at the stars even while he ploughed the furrow.

Clarke, who ran a cigarette kiosk (what man has not dreamed of a kiosk of his own?).

Constance Markievicz, who was by all accounts delusional, but there you go.

Devalera, later to be portrayed by my good friend the now-departed Alan Rickman.

Dreamers all. Dreamers of dreams.

The Irish for “dream” is “Aisling”, which is also a popular girl’s name, though less popular than “Robyn”.

The irony is not lost.

Did Connolly know anyone called “Robyn”? Unlikely.

“Is Ireland free now?”, Pearse would ask, surveying modern Dublin? How to answer? Where once the centre of power and communication was the post office, is it now situated in the Irish campuses of Google and Facebook, and Twitter, outposts of the global empires of the Internet?

“Did our gallant allies in Europe come to our aid?”, they would inquire. How to explain, then, the German and French central bankers who came to drown dear Caitlin Ni Houlihan?

“And the northerners?”, they would plead, and we would sigh “Not yet; not yet....”

Would they ask themselves if it had all been worth it, after we told them we had to get them all back to 1916 in time for their executions?

Returning to the time machine and their fate, waved off by a rosy-cheeked Robyn, on her horse, Pearse and Connolly and the rest would recognise that, for the country to finally free itself from the vulgarity of international corporations and the indignity of the European Union, there is only one path to follow. Ireland is one hundred years on from the glorious sacrifice of 1916. Now is the time to honour that sacrifice and rejoin the Commonwealth.