“People are broadly aware that they don’t like the BBC programmes, that along with some good stuff a lot of muck is broadcast, that the talks are mostly ballyhoo and that no subject of importance ever gets the honesty of discussion that it would get in even the most reactionary newspaper.”

“People are broadly aware that they don’t like the BBC programmes, that along with some good stuff a lot of muck is broadcast, that the talks are mostly ballyhoo and that no subject of importance ever gets the honesty of discussion that it would get in even the most reactionary newspaper.”

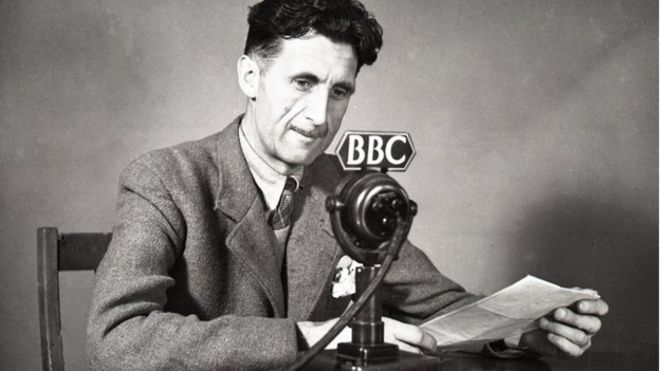

– George Orwell, Tribune, 21 January 1944.

George Orwell’s relationship with the BBC was, in some ways, typical of that of the literary, left-wing figure then and now. It was, to him, at various points, a beacon of fair-minded, scrupulous news coverage; a bulwark against the “vulgarisation” of the Northcliffe press; a government propaganda machine; a middle-brow muddle, a fusty Establishment megaphone; a source of pride, frustration, and, crucially, employment.

Orwell’s contribution to the war effort came in the form of service to the BBC, where he worked as a talks producer for the Eastern Service between 1941 and 1943. This was essentially a propagandist’s role: Orwell noted in his diary during his time at the BBC that:

“[O]ne rapidly becomes propaganda-minded and develops a cunning one did not previously have. E.g. I am regularly alleging in all my newsletters that the Japanese are plotting to attack Russia. I don’t believe this to be so, but the calculation is:

“If the Japanese do attack Russia, we can say ‘I told you so’.

“If the Russians attack first, we can, having built up the picture of a Japanese plot beforehand, pretend that it was the Japanese who started it.

“If no war breaks out after all, we can claim that it is because the Japanese are too frightened of Russia.”

We’re a long way from “If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear,” the proposed inscription next to a new statue of Orwell at BBC headquarters in central London.

The statue itself looks, in the manner of all modern figurative statuary, awful. Orwell leans forward in the manner of a pompous headmaster, admonishing all, with a cigarette in one hand. His clothes are Little-Tramp baggy, his cigarette held forth accusingly. It may be accurate but it’s still wrong (much like the same sculptor’s statue of John Betjeman at St Pancras station).

What exactly is the purpose of this statue? The BBC, presumably, hopes to enhance its reputation by emphasising its association with Orwell. Eton, his old school, which is part funding the statue, presumably hopes that some of the magic will rub off too.

Perhaps the erection of this statue is the final stage in the secular canonisation of Orwell, the final, sweet embrace of the Establishment.

Orwell’s appeal to the BBC and to Eton lies in a perception of his very specific Englishness, or his apparent embodiment of that virtue the English most like to bestow on themselves, “fairness” (or even “fair play”). And he is a very “English” (and hence, perhaps, unradical) writer. In his new book The Prose Factory, DJ Taylor notes of Orwell’s essays on English culture, “Here...Orwell is the small boy curled up on the hearth rug with his copy of Jules Verne or HG Wells, or rather the adult who regards the atmosphere of sensationalising American sub literature as morally inferior to the Billy Bunter stories and believes that a left-wing children’s comic is inconceivable for the simple reason that no child could be persuaded to read it.”

His experiences of the English establishment, from prep school to the Imperial police in Burma, placed Orwell on what we view retrospectively as the right side of arguments about class and empire, not to mention totalitarianism (the same horror at arbitrary authority can be found in Nineteen Eighty-Four and his essay on his pre-Eton schooling “Such, Such Were The Days").

But the biographical, complex Eric Blair is now far removed from the hagiographical George Orwell, the 20th century Tiresias. As Taylor points out, his “air of authority” “constructed out of huge generalisations” rather helps with this.

Orwell has become a cult figure not just for the English journalist, who views his “shot by both sides” life as proof of some sort of exemplary “objectivity”, but also ironically, for those of a vaguely libertarian viewpoint - the kind of people who wear Guy Fawkes masks and tweet memes about how Nineteen Eighty-Four was “a warning not a manual”, all the while emitting a vibe that suggests they’ve never actually read Nineteen-Eighty Four, let alone Orwell’s other novels, journalism, and (*shudder*) poetry.

The latter are the ones who will be most confused by the Orwell statue at the BBC. These of course are the people who will consistently tell you what the BBC is not covering when it is, or tell you that the current BBC model is not that different from Russia Today, when it clearly is.

Will they flock to New Broadcasting House to pay tribute? Will they protest at the Mainstream Media’s co-option of their hero?

Does the BBC know what it’s let itself in for?