The poetry of the periodic table

This is an edited transcript of a talk that took place at Birmingham’s Think Tank in November 2016 as part of Little Atoms’ Two Cultures series, supported by Arts Council England. Illustrations by Emma Wright

Zoe Schnepp: At a very young age, about the age of 17, I went to the Royal Institution in London and in the basement of the Royal Institution, I don't know if you any of you have been, but it’s a beautiful building, and in the basement they’ve got the lab that they preserved of Michael Faraday.

Some people say that if Nobel prizes had been around at that time he would have got at least four or five, because he did some amazing science. And he had this reputation – his mentor Humphry Davy was very much a womaniser and you know, the trendy scientist and everyone loved him, and he was always all about the self promotion and fashion. Michael Faraday was seen as this quite dour, serious man, who much preferred to be hidden away in the lab. But they've got in the Royal Institution one of his old lab books, and you open this one page of the lab book, and he wrote this in his lab book which I just think is – I hope one day I've got reason to write something as beautiful as this in my lab book – he said, “All this is a dream. Still, examine it by a few experiments, nothing is too wonderful to be true, if it be consistent with the laws of nature, and in such cases as these, experiment is the best test of such consistency.”

Isobel Dixon: I'm Isobel. And I've written – scattered through some books of mine – poems that link to the periodic table of the elements. My father was a science teacher, he was also a minister of the church. He was the very first person who taught me about the periodic table of the elements, which always fascinated me.

The idea of the coding, these letters that were sometimes very different to the names, and there was this whole history about the words that lay behind it, and that magical mysterious order of the periodic table fascinated me. And I started to think a few years ago of writing a series of poems that linked people in my family to a specific element. I have four sisters, and both my parents are no longer with us, but I had wanted to write a poem for my mother, which I linked to mercury. And I wrote a poem for my father, which draws in some facts and elements about carbon.

I don't know if you want me to say more about carbon, or read the poem now?

Littke Atoms: Probably best if we go into the poem then we can explore carbon.

Isobel: Great, OK.

Carbon

You loved the skin of the custard, the crust

of bread, joyfully accepted the cindered toast.

I'd be scraping off black outside the kitchen door

and you'd be crunching flecks of carbon

in among your marmalade –

charcoal in Roses Lime

dark crumb-frost in your shining beard.

Before I was born, before that beard

you looked like an eager boy, dressed all in black

except for the white stripe at your neck –

cassocked, buck toothed,beaming.

The nght before your operation I dreamed

you shaved it off. Frightening

to see you smoothed, erased that way

and in daylight, trying to shake the naked sense

of everything upside down, I realised

of course that they'd have had to shave you there, to cut.

The incisions and excisions, shearings

of the years, the stavings off.

The sun scars singed,

the sugar damaged digits lopped and cauterised.

It didn't end in fire. Laid, as they say to rest,

old bones in earth. You would have known

what kind of stone. I only knew

what it is to understand – hard knowledge – gone.

Holding for weeks, in my pocketed fist

the rosy quartz I'd pilfered from beside your bed,

held at the last, to absorb the warmth, against your skin.

From The Leonids (Mariscat Press, 2016)

Zoe will know why this is in the poem, why in a poem about carbon there is a rose quartz.

Zoe: In terms of chemistry?

Isobel: Yes

Zoe: Um, I don't know

Isobel: Quartz has got a silicon link hasn't it? And carbon on the table, silicon is right next, it’s below, and there are carbon mimicking properties

Zoe: Absolutely. Silicon's one of my favourite elements, and I teach periodicity, so as Isobel says silicon sits just below carbon in the periodic table. It's got some quite distinct different properties but it also does form quite similar properties. So quartz for example has quite a similar structure to diamond. That obviously is just carbon-carbon bonds.

I was going to bring a diamond but I ran out of space when I was running here from the carpark.

Isobel: The human body is made up so much of carbon, so in the poem about my father, life and death, that was part of that idea of life and death. He did love to have his toast burnt to a cinder.

He had diabetes late in life so had to have his toe removed and cauterised, and all that idea of the body and burning somehow stayed with me.

I did pick up a piece of quartz next to the bed when he died because the thing about rose quartz is if you hold it it gets warm quickly, it's a comforting feel in your hands, so it seems to absorb the warmth of skin quite well.

Zoe: Diamond is one of the best heat conductors, because its structure is made up carbon atoms with four bonds all equally spaced around it, and then that comes out from the centre and every single carbon is bound to the four next to it, and because of that structure heat transfers very fast through it. I don't know if it's the same reason with quartz, I'd imagine so.

Isobel: My science is not so good. I feel very much that my father would be looking down on me thinking: why didn't you do your homework better!

Zoe: You said about you know the silicon and the carbon being next to each other: as chemists we teach first year undergraduates to look at trends in the periodic table and to say, well I know carbon forms this structure, so silicon oxide in this case, if it forms the same structure the chances are its going to have similar properties.

The burnt toast was a nice point for me. A lot of my colleagues and friends joke that essentially I just do cooking in the lab. We do just stick things in an oven. It's a fancy oven and it costs quite a lot of money, but it is essentially an oven.

One of my other projects is in making materials a bit more like this a short carbon nanotube. It is made up carbon atoms, and the carbon atoms are arranged in hexagons and then those hexagons are all joined together to make a structure that looks a little bit like chicken wire. So if you then take chicken wire and roll it up into a tube, you've essentially got a carbon nanotube.

When you burn a piece of toast, the chances are you might have made one or two carbon nanotubes in there. When you burn organic material you get carbon in all sorts of forms, but people, if they're interested in this for an application for the strength of the materials, for the fact they conduct electricity, for the fact they might be interesting catalysts, people obviously want not just one or two pieces that have come off a piece of burnt toast.

So there’s lots of research into how to make these guys, and you can make them, you can make them perfect with expensive pieces of kit, an expensive process called chemical vapour deposition, which requires very high vacuum and it's quite a hard process. You can make them, but they are beautiful.

But one area of research that I was interested in was whether we take biological materials and make maybe not beautiful carbon nanotubes but rough wiggly ones that are a bit more like spaghetti.

I say that: in reality the science went that we were trying to do something else entirely and then we looked at the material that we made and discovered that we made all these long wiggly nanotubes and thought oh, hang on a second, these might have some nice properties.

But it all comes back to this iron material again. So it turns out if you take sawdust, or most biological materials, you cook them in an oven up to 800 degrees C, you just get this carbony mush, there’s no regularity in there. You can see lots of regularity in this structure, there’s no regularity in that one. But if you add a bit of iron – so again literally you take your sawdust and you soak it in a bit of iron nitrate, so it's not a complicated process at all, then you put it in a furnace, you get loads of these carbon nanotubes.

Some of them are big, some of them are small, some of them have got lots of walls, and they're all wiggly, so there's lots of defects, there's lots of irregularity in there, but they are still carbon nanotubes, the material still conducts electricity. So it's quite an interesting area of research, because it is essentially burning toast.

Isobel: The irony was that my dad spent loads of time and loved doing experiments at school. He was very very popular as a teacher, especially with the boys because he set up the experiments at great effort and he would use the Bunsen burners and cook things up, but at home he could barely boil an egg or he could possibly just make porridge. So there were two different spheres for him, although as you say they did have similarity. There was an incident once when people cooked scrambled eggs on Bunsen burners in the back of the class and he didn’t notice.

Little Atoms: You mentioned your favourite element, and you'd also said you’re also a bit scared of the science part...

Isobel: I love the science part. I'm not scared of it, I just feel that it's such a huge ocean of knowledge and as someone with a full time job and as a poet I don't do more than dip my toes into it. But that's one of the reasons as a poet I love commissions and I love doing work to do with science, so for my latest collection Bearings, I have a long sequence in there called Dark Matters, which is linked to a project I did with a composer inspired by ideas of dark matter. So that gave me the excuse to read a wonderful book called The 4-Percent Universe by Richard Panek, and my own self-imposed commission of the elements project which I'm still at the beginnings of gave me the excuse to buy lots of books on the periodic table, and dip in and read and expand one's knowledge back, and remind oneself of what one learnt at school, but learn more.

The Hugh Aldersey-Williams book Periodic Tales has lots of interesting anecdotes linked to the elements. The subtitle is “the curious lives of the elements” and it's well worth a read and a great book to just dip into if you want to read a little bit about something. So, no, I'm not afraid of it, I'm just more bashful with a real scientist next to me.

Caroline: Does that go the other way around? When it comes to people talking in a poetic or particularly emotional way around science?

Zoe: Absolutely. I was talking to one of my PhD students about this earlier. I told him I’d picked out this Michael Faraday quote and I said, “Oh, I'll probably feel quite silly reading it.” I love the literature and poetry side of life because I was brought up with an English teacher mother who took me to the theatre lots and forced me to love culture, which I resented at the time, but now appreciate.

Even as scientists we're quite daunted by how little we know, because I've done a chemistry degree and I studied lots of organic chemistry for example when I did my degree, but having them moved on to a PhD and specialised in materials and biology, I could talk for hours on biological molecules, but I've forgotten everything I ever knew about organic chemistry. I would find it very difficult to have a conversation with one of my synthetic organic colleagues for example. So even within chemistry you can feel quite at a distance I suppose, from people who are supposedly in the same field as you.

Caroline: It's interesting when you think of arts and science of being siloed themselves, but to know that even within that you can go, you can get these further divisions.

Zoe: Art in science is something that's becoming more recognised or encouraged. Encouraged is probably the better word. Because certainly when I think about loving literature and reading,I see that as quite a separate thing from my work, I'll read before I go to bed and I love reading, but as I said, linking art and science is certainly something that's becoming more appreciated and I think from both sides, so scientists quite enjoy the images and you can create some lovely images from samples and...

Isobel: Research always has elements of the imaginative leap and of play, you're playing with ideas and you're playing with the things that you're looking at, the things you look at through the microscope. You're imagining how they might behave and you devise a test to see if what you have imagined might be true, and sometimes it is and somethings it isn't, so I think the arts and science are not as far apart as people tend to think. I don't see them as separate things, and there are countless examples of poets and writers inspired by science. I mean I haven't read all of Primo Levi's short story collection, The Periodic Table but I know they are wonderful stories, 21 stories in which each story is linked around an element and have autobiographical elements in it, and among my close circle of poet friends I have other poets who have worked on things to do with science.

Simon Barraclough wrote a whole book called Sunspots. There’s also a collection about the planets, Neptune Blue.

There’s endless inspiration to be found in the natural world, and in that detail of science and research.

Zoe: Birmingham University has a little internal magazine, which might feature someone from different schools of research, and one month I was flicking through and they were talking about the artist in residence, who was a woman working up at the Winterbourne House where there's some nice gardens, and she was working on a process where you can use something called Prussian Blue, which is a dye, and she basically takes flowers. So this dye, you mix up the precursors, and the reaction to make the blue dye is driven by light.

So you can use it for “cyanotyping”: it's a type of photography. She'd take beautiful leaves or flowers, and lay them over paper that she'd treated with this mixture, and then expose it to light, and the bits where the flower wasn't would go blue, and where the flower was would be a white outline. She experimented a lot and made some beautiful images. Which I thought was great, I went to see her in her studio to see some of the pictures, which were gorgeous. And I thought, you know, I've got to go back and try this. So I got the chemicals and mixed them together, and put it on some paper and I can't remember what I used to shield it, but I left it in the light for a while and got this lovely blue outline. Which I thought was delightful.

Now I've got a PhD student working on this dye, and trying to make these catalyst materials, because it's iron – I love iron!

Genuinely one of my favourite current research projects, has come out of talking to this artist, and going away and thinking I wonder what the science is behind this lovely blue colour, so it definitely can work both ways.

Little Atoms: You've spoken a lot about scientists being inspired by arts, and I was wondering in terms of poetry is there a scientific rigour to poetry.

Isobel: I like the idea of the structure, the order of the periodic table, the form, the periods which are the rows and across, the seven rows across, and the groups, the 18 columns, and I write my poetry in lots of different forms and often it's just the subject matter or where the poem begins which dictates the form, but I do love form. So I for instance enjoy the challenge of writing a proper iambic pentameter sonnet, a 14-line sonnet, and a haiku in a 5-7-5 structure. I think there's something about human nature but also our aesthetic love of symmetry and of patterning that finds itself in music – you know, recurring choruses and patterns in music – and in form, and both how our ear recognises that form is being respected, but also aesthetically how the eye sees the poem on the page.

My eldest sister reminded me of my father showing us the Disney film Donald Duck in Mathemagic Land, which I absolutely love, I can watch it again and again and again. It shows you the wonder of form in the natural world, the golden mean and how nature does this patterning which explains I think why we love it so much.

Little Atoms: Well aside from carbon you've both got other elements in common. Mercury, I was wondering if first we could start off with you.

Zoe: I have never worked with mercury, I hope I never will. Mercury's a bit of a scary one. It's got a lovely history though. There's a nice book called Crucibles: The Story of Chemistry, which I'd recommend. It's not written towards scientists, it just gives a history of alchemy and where chemistry came from, and gives a nice perspective on the problems that chemistry faced as a science because chemists did evolve from these slightly crazy alchemists who were trying to transmute lead into gold, and had lots of bubbling pots of mystery, so mercury has definitely been an element of some fascination.

Personally there's the more horrible tales of people who have died, scientists have died from using mercury and being exposed to it. Not mercury itself but compounds made of mercury. It's certainly one I've steered clear of, but it's inherently fascinating, I mean it's a liquid metal! I remember I was lucky enough to be at a school where we had a physics teacher who had a room full of things she probably shouldn't have who dug them out at occasions, so we did get to see some mercury in a bottle. It is, it has a certain appeal to it that you don't get from any other element.

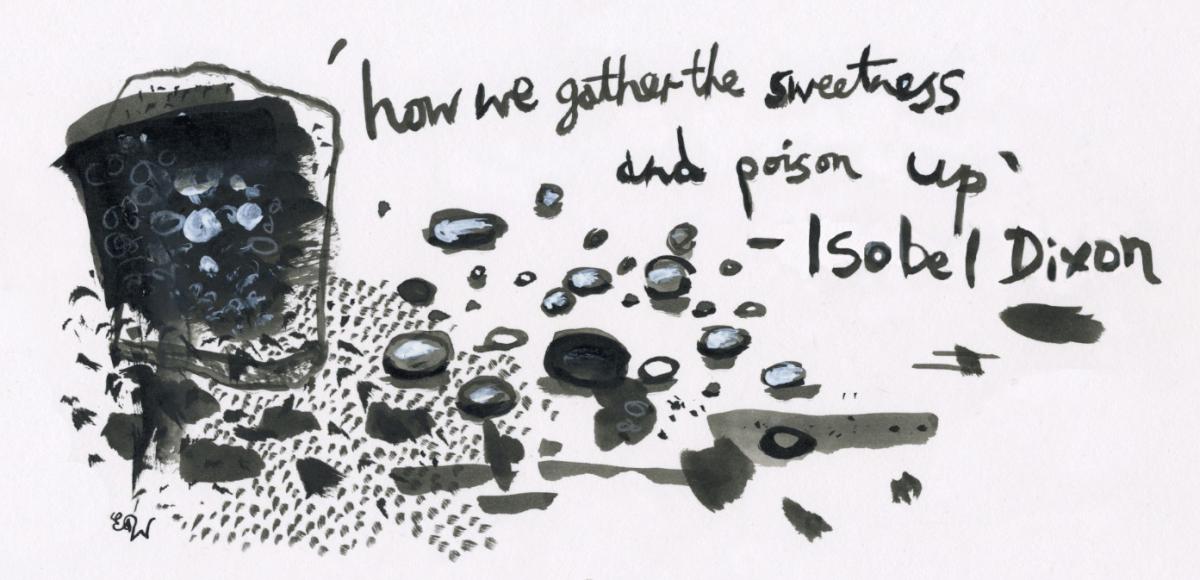

Isobel: It is quite magical. One of the things I loved is the question of coding. Why is sodium Na? The fact that mercury has Hg which is not even in its name, and its I think hydrargyros meaning water silver. So I have a poem called Mercury. So this one is about my mother and in The Leonids they're on facing pages [Carbon and Mercury]. The Leonids is a collection largely about my mother who died last year, and she had all her life struggled with depression. She had quite serious postnatal depression after me, so the poem does reflect somewhat on that volatility and also the idea of the beauty of mercury and also how we I remember when you;d have a thermometer with mercury and it would break, that I remember as a child picking up the mercury because it did that wonderful thing of how the globules would leap together. Of course very dangerous, not a very good thing to do. So anyway, this is a poem for my mother called Mercury.

Mercury

My mother's pantry cupboard spreads

its pink special occasion wings.

Frugal cornucopia, edible tinselling.

O hundreds-and-thousands, O boundlessness!

Shaking the rainbow in anticipation

of the glacé cherry on top,

the butter icing on the cake,

and the silver globes, the little silver globes

which, sucked, turned disappointingly white.

I want them precious, right the ways through

Want truer spells, like the fever broken

like the glass wand snapped,

a stick of crystal candy rock

with its vein of revelation spilled.

Errant spheres to chase

across the brown linoleum,

playing planet-maker, risk-taker,

charm-on-lifeline swirler,

conjuring girl. Magically shepherding

the wayward, shining, merging flock.

Sorcery on the kitchen floor –

liquid metal, the brilliance contradictory.

Sisterlode, motherlove

the cleaving madness of family.

Mom, I am too far away to stroke your brow,

take your temperature, feel your pulse.

But I am probing this half-knowledge cupped

in my palm – how we measure

the heat of the generations now,

how we gather the scattered sweetness and poison up

Little Atoms: How did your parents influence your choices, in terms of the field you ended up in?

Zoe: I'm not sure. Certainly my mum, although she was an English teacher and she used to take me to the theatre and make me read a lot, she also encouraged me in the technical side of things. She'd buy me lots of Lego and Meccano, and science toys; she took me to the science museum. So she was very keen on me having that education.

Certainly I took to that side of life more readily. I don't know whether that's nature or nurture, from an early age I liked that side of things.

Chemistry itself though was a bit of a mystery to my parents. My dad studied maths with physics and would have encouraged me down that road. But I just seemed to like chemistry.

Some people have stories of something that particularly inspired them, but I just liked the lab, I liked the smell of it, I liked the glassware, and bubbling things, and it was just something that appealed to me. So I think the choice of sciences was just kind of evolved for me.

We had open days at our school where kids from local primary schools would all come in. And I remember all the way up through school it was always a year 13 student who got to set up this beautiful bit of kit. You'd get loads of orange peel, you'd boil it up and you'd distill off limonene, which is one of the compounds in orange peel that makes it smell so nice, and you'd get a few little drops of this lovely orange oil out the other side, and I remember all the way up through the school, from year 7, year 8, year 9, going around helping out on open day, and seeing this A Level student girl who'd be doing this distillation, this beautiful bubbling kit, and I'd be so envious.

Isobel: And did you become that girl?

Zoe: I became that girl! I can remember lots of those moments, but I don't remember a moment where I thought yes chemistry is for me, it was just lots of moments where you know this just had a pull.

Isobel: Life is composed of lots of those little moments that tends the rivulets of your experience to go down a certain way. My mother wanted to be a librarian, but never got to go to university, but she was also very very good with numbers and very practical, and she was the one who rewired the plugs, and did things like that in the house.

My father was a minister, so in weekends he'd be writing his sermons. He loved poetry and could recite poetry and could teach Shakespeare just as well as he taught maths or science, so I think all five of us we grew up loving reading, loving playing chess, enjoying science. Most of my three older sisters all went much more in numbers and sciency routes. I have a sister who's a doctor, a sister who did a BSc in agriculture, a sister who worked in a bank, so a mix. But I always knew, although I loved having the adeptness at science and maths – I enjoyed the puzzles, and so on of that at school – I knew I didn't want to do that at university. I always knew I wanted to do something to do with literature and writing.

I thought I’d be an academic, and then I realised halfway through my Masters in English, that I didn't want to do a PhD because I didn't want to deconstruct texts – I wanted to be involved in making them. And although I'd only started writing myself tentatively, I’d written and published some poems, I fortunately fell into my day job, my day and night job it seems, of being a literary agent, so I work in publishing and I'm a poet. It's a very writerly life, which is why the opportunity to do things with science satisfies an appetite that I still have.

Little Atoms: Take me through just an average day, if there is such a thing as an average day.

Isobel: My days are very very multifaceted because my job involves finding writers, reading new work by writers, deciding who I think has both talent and is someone that I can work with and sell. I have a strong list of writers that range from the commercial through to the literary, and when you have to match them with publishers, so my days are a mixture of text (although the text stuff usually happens on the train or at night, or on the weekend) and writing submission letters, writing editorial letters, submitting the work to publishers that I've identified would match with that writer, negotiating deals, checking contracts, arguing about covers, selling translation rights. It's incredibly various and no two days are alike, which is why I love the job.

Zoe: I'd say exactly the same thing. The variation day to day is what I love about the academic life. Teaching is a fairly significant part of my job, working with undergraduates, training research students, supervising their research, and then writing papers, submitting. So it's not so different. I spent a lot of my time at my desk, you know: please publish this paper!

There are a lot of these administrative roles like making the corrections for a publication, deciding on cover art, making sure all the other authors on the paper are happy. It's never such an issue, but just making sure everyone's approved being published, and getting everyone's corrections, and then the teaching side of things too.

And I then treasure the times, so over the summer when the students aren't around, where I can say devote a week to a load of data or I can go in the lab for a week and be that creative side of my job.

So this summer for example I'd spent some time at, there's a big synchrotron source down near Oxford, and I got a whole load of data from that.

I was at an institution called Isis, unfortunately, which is a neutron research facility, which basically fires out a great long beam of neutrons, and you can use that to study soft materials, so gels and things in solution, you could study the structure of shampoo. Shampoo has structure. Using neutrons. And gelatine, and the gelatine structure you can study.

And I had all this lovely data from the neutron source and I was able to sit down and play with it. I would say I've spent the afternoon playing with my data, I'd say to my husband when I get home, he's a scientist too, Ohh I was about to play with this data today, and I made some beautiful graphs. And we do use this language.

Isobel: The language of beauty and play...

Zoe: Absolutely, and I sometimes print out graphs that are particularly beautiful and stick them on our office wall.

I think our days, jobs aren't so different. It's interesting because I imagine you treasure the time when you can sit back and spend some time on the creativity and do your own writing.

Isobel: Absolutely. Quiet time to write or even again just to immerse myself in something that I don't have to edit, I don't have to think about the function. Although I love my job, and I love the writers whose work I represent, there is something about being free to explore that freedom in the text.

Little Atoms: There are similarities but there are big differences in both of your fields...

Zoe: Probably the style of writing. While I love to come up with a particular sentence structure that sounds nice, inherently I'm telling a scientific story and I have to be very careful with words and make sure I'm not putting a slant on it.

People sometimes say scientific writing is quite dry. I don't think it's dry, I think you just have to be very careful with the way you phrase things. You are laying out facts and I think a good scientific paper will make suggestions and draw conclusion but also clearly lay out the data and tell a story in the way that the reader can seal facts and make up their own mind. In style of writing it's a very different.

Isobel: You are seeking to draw a conclusion. I'm not necessarily seeking to draw a conclusion. I might be seeking to stimulate ideas. Sometimes I’m telling a story and other times I might just want to explore an idea, and sometimes it's completely mysterious why I'm writing something. I may not realise completely in the middle of a poem, or perhaps even when I’m finished, what I'm doing, but it is something that emerges from the subconscious and the conscious mind, and the echoes of things.

In my collection Bearings, I have a sequence of poems organised in quartets, seven line, four poems, four stanzas of seven lines each with each title begins “In which”, and they're almost a repository for me of scraps and fragments of thoughts, ideas, phrases that somehow stick in my mind. I was describing it to my husband as my poetic Tourette's, and he said no to me it's more like phonetic Tetris.

There's a compulsion for me to write them, but I can't tell you that you're going to draw any conclusion of get any facts from them.

Zoe: I think that's the key difference, alongside my writing is all the evidence, we have to provide evidence for everything. You can speculate, but you have to make clear that you're speculating. I'd say when I write a paper I spend more time on the figures and getting the data in the right format than I do on the actual writing, because the evidence is key to the scientific paper.

Little Atoms: But at the beginning of that process, when it comes to the playing with data?

Zoe: The very beginning is very scientific in that you, well first of all you have to get the funding to go to these lovely facilities, so you write the proposal, but when you're planning the experiment, that's very logical, in that you have a hypothesis and you think “OK well, what are my contingency plans, what's my plan A, if that doesn't work, what's plan B, what's plan C, what's plan D….” But again it's all very structured and maybe at the end perhaps you've got time to say “You know what, it'd be very cool if we ran this sample, and let's just try this and have a bit more of a play.” And then you go away and you've got the data, and then “Let's just compare these two, this is interesting, let's plot it like this, or let's try fitting it like that…” and that's the more fun part I suppose, and then at the end it's the writing it up, and that's back to the quite structured. There's other parts of my science where it might involve days of playing in the lab: “let's see what happens when these get mixed together, or what happens when we heat this up”

So there is always, I'd say in every experiment, every piece of work, there's always a stage that is fun and creative and enjoyable.

Little Atoms: Up until this point you've both spoken a lot about your previous research and the whole point of Two Cultures in Conversation is to get you talking about what you're working on at the moment and anything that might inspire either of you.

Zoe: Something I love in my research is to study mechanisms and to work out how something's formed. So we make all these materials from these biological materials, how is that biological structure controlled how our new material grows, and we, what we did at this Isis institute was to study the way the gelatine assembles itself in solutions, so gelatine in your jelly, you pour the boiling water on the jelly and you mix it up to dissolve it, and what happens is the gelatine molecules in the hot water are all floating around all over the place, just random spaghetti.

And then as they cool down they gradually twist round each other to form these triple helices. It turns out when you add iron in there you disrupt these triple helices, so it stops forming those triple helices, and instead the iron just pulls two bits of gelatine together like that.

This is our postulation based on our data that we got at this Isis institute by studying the structure with neutrons. That's something that I love at the moment, and I guess the other side of it is taking carbon forward and something I would like to do is work in water treatment.

Arsenic's a big interest of mine at the moment. There are a lot of countries in the world that have a problem with arsenic in the drinking water. It's not a pollutant as such, it's not come out of a factory or leached out of car engines or whatever, it comes naturally from the rocks into the groundwater, but it is a poison. Arsenic's quite famous as being a poison, and so I'm quite interested in working with some of my carbon materials and seeing if there are any good at removing arsenic from water and that's something that's a big passion of mine to move forward on into the future.

One of the biggest issues came in Bangladesh. Obviously Bangladesh is famous for flooding and a lot of people were getting diseases from drinking water from rivers, rivers that were then polluted with faeces and a lot of poisonous pathogens. A lot of charities went in and drilled wells so people could get the well, the groundwater which obviously didn't have all of the pollutants with the pathogens in, but the trouble is the groundwater then contained the arsenic which had come out of the rocks.

And there's a quite high incidence of arsenic poison. So no it's a it's a sad story but there's a lot of interesting science behind it. Actually the chemistry of arsenic that I've come to learn is interesting. And you can use sunlight to change how the arsenic behaves in the water and whether it sticks to carbon more or less, or there's all sorts of clever chemistry, which I've enjoyed learning about, so it's something that I'd like to move into.

Isobel: I'm always working on several projects at once so the main project I'm seeking to go further with is not specifically science linked, it's something called Birds, Beasts and Flowers. I'm working with an artist and a composer on a response to the poems in DH Lawrence's collection Birds, Beasts and Flowers, looking at the natural world and travel and so I've poems on bees and snakes, and there will be both illustrations and an exhibition with artifacts, and a few of the poems will have music as well.

So I love that kind of collaboration. I'm pottering on with my periodic table of the elements, I have notes towards iron, I have had interesting conversations with my sisters about which element they think they should be, each of them. I've done my parents so now it's the four sisters to come.

Little Atoms: And what element do you think you should be?

Isobel: Oh, I'm not telling! I'm a Gemini so I can pick two! No so, I have notes towards other ones. I was brushing my teeth earlier and thinking about the fact that they used to put radium in toothpaste in the past. All of the ways we've used bad things, so I've got notes for antimony, and various of the elements but not quite there yet. And I tend to work on lots of things at once, and then the time will come when those notes somehow crystalise like in the petri dish, things all come together in that way.

It was interesting though when you were talking about the water, I was remembering that at one stage I wrote a sequence of poems called Fibs in the form of fibs, in the Fibonacci sequence, so where it becomes a right-angled triangle, where the first line is one syllable, the second line is also one syllable, because you add one, and then the third line is two, and so then the poem I did some time back was about the Union Carbide scandal, the disaster at Bhopal, where the Union Carbide company allowed everything to be poisoned by their plant.

Zoe: A big passion of mine in teaching is educating undergraduate chemists about things like toxicity toxicology, and also chemical disasters. And also where has the chemical industry gone wrong in the past and how does the chemical industry need to change in the future? So Union Carbide is a big story.

Isobel: In fact I was sitting on the train next to a chap who is an air quality controller, so he was quite interested in why I was looking at all these books about chemistry and the periodic table. We ended up having an interesting conversation about Bhopal and various other poisonings.

Caroline: That leads me onto my final, it's more of a point than a question, both of you working with the periodic table and materials in particular. Would you say that's true about how you came to be inspired by the periodic table? Or interested in it? In elements? The fact that it's quite a tangible thing?

Zoe: I take a certain pleasure in collecting elements which is going to make me sound geeky now. But they were having a clear out in a lab when I was working in Japan and someone dug out there was a whole load of samples of different metals, and I was like “oh I'll have those”.

Something I've enjoyed in my career is working with so many different elements, and I've got a little periodic table where I check them off as I work with them.

Praseodymium is my most exciting one so far. I'm not necessarily in the elemental form, but in some compound, you know. So, as an inorganic chemist – as chemists we divide ourselves up into organic chemists, inorganic chemists and physical chemists, and the organic chemists are pretty much carbon and organic molecules, and physical chemists study properties of materials and processes, and inorganic chemists we get the whole of the rest of the periodic table, you know, it's great fun.

Isobel: It's a snapshot of the whole of life – you know, everything is there so so it's a gift as a poet because you can say you're writing about X, but you can go off in so many different directions. It's a lovely magnifying glass, you can shape up that whole table and find something to write about.