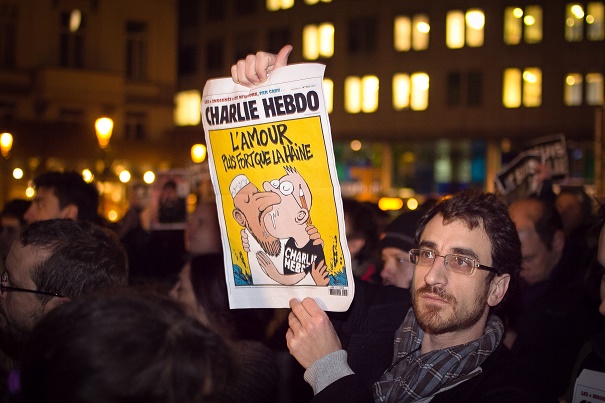

Teju Cole, Peter Carey, Michael Ondaatje, Taiye Selasi and other writers have decided to withdraw from PEN American Center gala honouring staff of Charlie Hebdo.

In an email interview with the New York Times, Carey questioned whether the Charlie Hebdo case was something PEN, established in the 1920s to encourage free expression and solidarity among writers, should even be involved in.

“A hideous crime was committed, but was it a freedom-of-speech issue for PEN America to be self-righteous about?” the Oscar And Lucinda author is reported as saying.

This is not a joke. This is a renowned novelist questioning whether the murder of magazine staff - specifically because of what they published – is a “freedom-of-speech issue”.

Carey apparently believes that PEN should only get involved in clear cut cases of state censorship. This is not only an outdated notion of how censorship works, but also a very, very narrow reading of the PEN Charter, which states:

“PEN stands for the principle of unhampered transmission of thought within each nation and between all nations, and members pledge themselves to oppose any form of suppression of freedom of expression in the country and community to which they belong, as well as throughout the world wherever this is possible. PEN declares for a free press and opposes arbitrary censorship in time of peace. It believes that the necessary advance of the world towards a more highly organized political and economic order renders a free criticism of governments, administrations and institutions imperative. And since freedom implies voluntary restraint, members pledge themselves to oppose such evils of a free press as mendacious publication, deliberate falsehood and distortion of facts for political and personal ends.”

One could, perhaps, question whether Charlie Hebdo breaches the preceding affirmation in the PEN charter, which commits PEN members to “pledge themselves to do their utmost to dispel race, class and national hatreds, and to champion the ideal of one humanity living in peace in one world.”

I don’t think it does, and nor, clearly to the people at the head of American PEN. It is deeply anti-religious and anti-clerical, yes, and the satire is crude, but the motivation is not to provoke racism.

As the best paragraph of the excellent PEN Center statement on the issue states:

“The rising prevalence of various efforts to delimit speech and narrow the bounds of any permitted speech concern us; we defend free speech above its contents. We do not believe that any of us must endorse the content of Charlie Hebdo's cartoons in order to affirm the importance of the medium of satire, or to applaud the staff’s bravery in holding fast to those values in the face of life and death threats. There is courage in refusing the very idea of forbidden statements, an urgent brilliance in saying what you have been told not to say in order to make it sayable.”

There is a clarity here that the likes of Cole and Carey seem unable to abide: free expression exists not just in sentiment, but in action. As Jamie Bartlett has pointed out about free speech in an article for Little Atoms: "Liberals... know what it means in theory: but without regular exercise, they have forgotten the practice."

It is all very well to state one’s support for free expression as an abstract, as almost everyone does, but if one cannot express solidarity with people who are murdered for exercising their free expression, then you don’t support free expression. It actually is that simple. I wonder sometimes if the likes of Carey and others tie themselves in knots over these things because the simplicity itself is unappealing: “Where’s the angle?” they think. “Where’s the fresh perspective I can bring?” “What’s the clever thing to say here?”

But while they might reject simplicity, they embrace certainty. They are quite sure that they will never be Charb, they will never be Charlie, they will never be Rushdie. They, being good and right, will never find themselves in the middle of a global storm, or staring down the barrel of a gun: not because they are scared to provoke, but because they only speak and write in self-evident truths with which no one could disagree.

The response of Salman Rushdie – who knows of what he speaks – to the line taken by Carey, Michael Ondaatje et al is unimprovable:

“If PEN as a free speech organisation can’t defend and celebrate people who have been murdered for drawing pictures, then frankly the organisation is not worth the name. What I would say to both Peter and Michael and the others is, I hope nobody ever comes after them.”

Quite.