The Sentencing Council of England and Wales has launched a consultation “on its proposed guideline for reduction in sentence for a guilty plea.”

The proposed sentencing guidelines are intended to encourage earlier guilty pleas, and are viewed as a move to help make the criminal court system more efficient, ensuring that cases don’t hang about unnecessarily, and also trying to make sure that victims of crime aren’t dragged through lengthy and painful proceedings.

This news was met with a range of responses in the press. Some highlighted that it “should help speed up the efficiency of the criminal courts” (the Financial Times), while others chose to focus on the fact that they appear to be recommending that “criminals should have their sentences cut by up to a third if they plead guilty even when there is an overwhelming case against them” (The Times).

Is there a risk that defendants could feel pressured into an early plea, regardless of whether they are actually guilty?

The guideline explicitly states that “nothing in the guideline should create pressure on defendants to plead guilty”, but nevertheless the question must be asked: Will the defendant have enough information about the case against them to make an informed decision on whether to plead at the “earliest stage”? Is there a risk (particularly for minor offences) that defendants could feel pressured into an early plea, regardless of whether they are actually guilty? For some, there is a real fear that these changes may encourage people to plead guilty before they have a real understanding of the case against them, and this is not justice. (Matthew Stanbury from Garden Court North Chambers has written about this in the Justice Gap).

In a move that now appears far more cunningly planned than it was, Fair Trials this week launched a new campaign around the use of plea deals around the world. The project aims to document the use and abuse of plea bargaining worldwide, and will consider its application in around 70 countries.

The arguments in favour of plea bargaining are obvious, but nonetheless compelling: reduced costs (particularly attractive in these austere times); increased efficiency of courts and prosecutors (ditto); the idea that as defendants accept their responsibility, the responsiveness to criminal punishment increases; and the suggestion that it can help to combat organised crime by incentivising cooperating witnesses. The arguments against plea bargaining, however, deserve to be heard.

"97 per cent of US federal crime cases never reach trial"

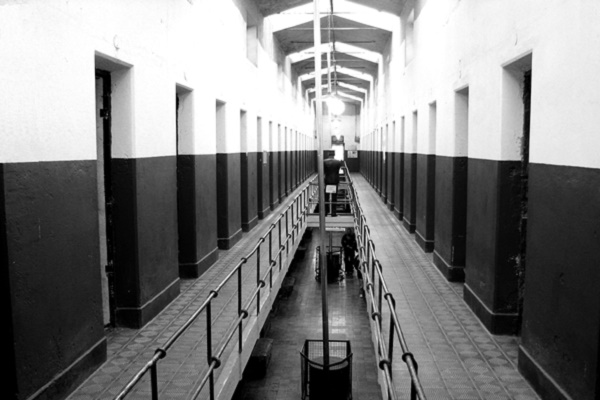

Looking at the US, seen by many as the spiritual home of plea deals, 97 per cent of federal criminal cases never reach trial. All well and good if everyone involved is guilty, but it is estimated that 20,000 factually innocent people are in prison for crimes to which they have pleaded guilty but did not commit.

In cases concerning less serious crimes, plea bargaining is often seen as a cynical enterprise in which ill-advised, ill-resourced defendants plead guilty simply to obtain release from pre-trial detention, with minimal investigation from either prosecution or defence. Even where convictions for minor offences do not carry jail time, there can still be serious and lasting ramifications. They can jeopardise benefits, housing, employment, migration status, and parental rights not only of convicted people but also of their family members.

In felony and federal practice, defendants are routinely required to waive rights beyond the right to trial—to appeal, to examine all relevant evidence, even to complain about the legal advice to accept a plea deal.

Plea deals can make it easier for prosecutors to seek convictions. To create a strong enough incentive to plead, countries may also increase maximum sentences and restrict judges’ capacity to restrict sentences. This potentially results in higher prison populations. Not only this, but the potential sentence a defendant will receive after trial is so much more severe (estimated by some researchers to be on average 65 per cent longer) than the sentence offered through plea bargaining. This means that most defendants judge it to be in their best interests to accept pleas, regardless of the accuracy or strength of the government’s case against them.

As concerns raised through US practice and these new developments in England and Wales illustrate, there is a real need for the fairness of plea bargaining systems to be pushed further up the global human rights agenda. It is on the rise worldwide, and while this sentencing announcement does not put us in the same league as the US, it does still cause pause for thought.