What's happening in Dunkirk's Grande-Synthe camp?

A volunteer at the site reports from the ground

Until recently, France’s "forgotten camp" on the outskirts of Dunkirk, home to some 3,000 men, women and children, had received little media attention. Even at the neighbouring Calais site, just 30 minutes down the road, the Grand-Synthe location was relatively unknown.

I first visited the camp in Grand-Synthe last November, after hearing about it from a long-term volunteer in Calais. At the time, I was in Calais with a group fans from Dulwich Hamlet, my local football club, delivering aid donated by other fans and local residents. We had managed to collect over two vans and two cars full of donations, plus extra items that we donated to local foodbanks. After our first visit to Calais, we decided to donate what we had left to the Grand-Synthe site.

"The address of the camp was, until recently, a closely guarded secret."

But of late getting aid into the camp hasn't been easy. For the last three weeks, a new by-law has seen police permanently stationed at the entrance to the camp preventing supplies such as tents and building materials from entering the site. At times this even included sleeping bags, gas, firewood, tarpaulin and food.

The suburban camp in Dunkirk’s Grand-Synthe has a much shorter history and none of the same notoriety. The address of the camp was, until recently, a closely guarded secret. This was in part to avoid the chaotic scenes witnessed at the Jungle, where many well-meaning people arrived with all sorts of supplies for the residents of the camp, unwittingly adding more work to the camp’s already overstretched capabilities. Inappropriate items, such as wedding dresses and suit jackets, end up being dumped either by residents or by volunteers who, overwhelmed by the need and desperation they are faced with, often end up leaving the unwanted goods behind.

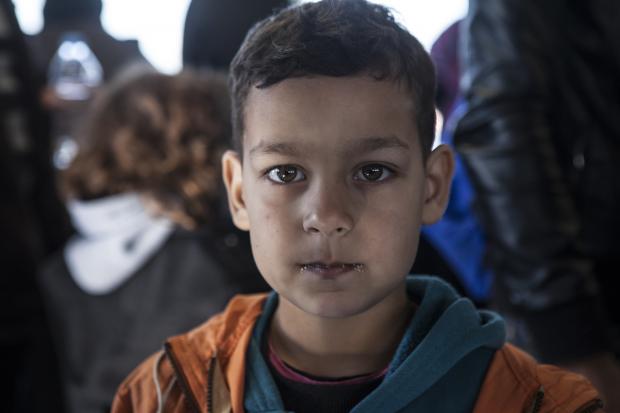

The makeup of the camp also doesn’t fit with the dominant narrative. Rather than the supposed marauding gangs of feral young men taking death-defying risks to smuggle themselves into the UK, the picture in Grande-Synthe is one of families, pregnant women, babies in arms all struggling to survive in the unrelenting rain and mud. Many of the families in the camp are Kurdish and have come from Iran, Iraq and Syria. There are a few Vietnamese residents and until recently some Sudanese. The hierarchies that exist within the camp means there are often restrictions on people from certain ethnicities accessing aid and tensions between minority and majority groups.

Conditions in the camp in the suburb of Grand-Synthe are squalid. The majority of residents live in flimsy, damp tents, unfit for an English summer festival let alone the north of France in an incredibly wet winter. What was once a football pitch became a muddy bog. By January, as a result of almost non-stop rain for many days, the centre of the camp resembles a stinking swamp. Many tents were flooded and others washed away leaving 200 residents without shelter. Volunteers on the ground had been unable to replace them due to restrictions on aid coming into the camp.

Residents have little in the way of infrastructure present in the Calais camp. The showers have been broken for four months, and before that they were often freezing cold. Simon Lewis, head of UK emergency planning response at the British Red Cross described the conditions as inhumane. “People are surviving on very little. There’s no electricity, heating or waste management. The lack of toilets and showers mean people are living in appalling and inhumane conditions.”

With the exception of MSF, there are no large charities permanently on the ground, and no signs of government support. Aside from a kitchen that has the capacity to serve 200-300 meals a day and a small school, there is simply a submerged field and groups of untrained, under-resourced volunteers like myself, all doing our best in an impossible situation.

Long-term volunteers, who are already stretched to breaking point, are having efforts to support residents frustrated by a French state determined to squeeze the camp and stamp down on morale. Tents, clothing and belongings destroyed by the terrible weather conditions cannot be replaced and residents are wet, desperate and hungry.

On 11 January a temporary reprieve was granted, allowing new tents onto the site for one day. Volunteers from across the UK and neighbouring Calais turned out in force to provide tents and sleeping bags. A walkway was also built to help negotiate the ever-increasing mud. However, allowing volunteers a single day to swap out broken and damaged tents for new ones is an inadequate response to the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Grand-Synthe.

Since that first visit to the camp in November, I have been over again twice and some of my teammates spent Christmas there. The terrible weather conditions, mud and increase in numbers, let alone the aid blockade, means meeting the needs of residents has become a mammoth task.

Authorities have now given the green light to a new purpose built site overseen by MSF to replace the current site at Grand-Synthe. The new camp came with a promise of higher standards, including heated tents, proper sanitation and medical care but there is concern about whether volunteers will be able continue to support the residents.

Increased living standards would clearly save lives and prevent the disease and ill health currently spreading through the camp. According to MSF the new camp will be ready in four weeks but will only have space for 2,500 residents. Volunteers on the ground suggest that a camp of that size would take at least two months to build. Even by conservative estimates, the residents will have to remain in the current conditions until mid-February, seeing out much of winter in flimsy, damp, nylon tents.

But questions remain around whether residents will be required to apply for asylum in France, whether residents fingerprints will be taken (as it's rumoured that access to the new shipping container camp in Calais will be by fingerprint), and if residents will really be able to come and go as they please.

Many of the residents are reluctant to move to the new camp because what they want is to come to England, where many have relatives and speak the language. They don’t need better tents, they want our government to open the borders so they can start a new peaceful, safe life here with us. The reality is that this is unlikely to ever happen so the people in the camp in Grande-Synthe, and in Calais, will continue to risk death in search of a better life.