Syria’s economy is being battered by a conflict that is now on the cusp of entering its fourth year. Real GDP declined from $60 billion in 2010 (the last pre-war year) to about $33 billion in 2013, a year in which the economy shrank by 16.7 percent. Syrian exports showed a 95 per cent slide in 2013, while inflation is estimated to have reached 90 per cent. More than half of the population is now unemployed.

The UN Economic Commission for West Asia (Escwa) estimates the losses incurred by the Syrian economy throughout the three years of conflict at $140 billion dollars, of which $69.1 billion dollars (almost half) is the value of the losses in monetary supply. The private sector has borne the burden of these losses, with $96 billion – around 68 percent – of the total economic loss. The Central Bank’s foreign currency decreased from $14.4 billion dollars in 2011 to just $3.5 billion dollars at the end of 2013.

All this is as nothing compared to the loss in life – as high as 200,000 by some measures – and the displacement of at least 20 percent of the population. There are now 1.5 million Syrian refugees in Lebanon, as well as significant numbers in Jordan.

Constrained from generating sufficient tax income to support its spending priorities, the government budget deficit has grown from just 3 per cent of GDP in 2010 to 33 percent, according to a policy brief from the European Council on Foreign Relations. Public debt is now equivalent to 126 per cent of GDP, and rising fast. That limits the government’s capacity to import vital commodities, whether food or fuel stuffs.

The biggest hit comes on the country’s oil and gas sector, its one reliable generator of hard currency export earnings. Pre-war production of 400,000 barrels a day (b/d) has diminished to less than 30,000 b/d in 2014 – down by half from last year, and a good slug of that output is under the control of Islamic State militants. They sell barrels on the black market to whoever pays the highest prices. Estimates suggest the government is effectively getting barely more than 15,000 b/d of crude oil.

Despite this bleak picture, a number of Syrians are doing very well out of the crisis. Business activity has not been completely smothered, and government services are now concentrated on a smaller segment of the country under its control – preserving resources. It does not bother with providing services to rebel-held areas north-east of Aleppo. In the Assad regime strongholds of Tartous and Lattakia, where large numbers of Alawite Syrians live there is an ongoing construction boom, as Damascus-based investors relocate their businesses to a relatively safe area of the country.

Fresh licenses for industrial plants are being issued in these areas. Business owners have to overcome numerous challenges, such as having to shift their machinery through checkpoints manned by groups who demand payments. But once in Tartous, says one Syrian banker, “they have the benefit of a port with access to a wider regional market.”

The banker says the centre of Damascus is relatively unaffected by the conflict, which contains about two million of the highest-income Syrians. However, the surrounding areas – still largely held by rebels – are off limits and subject to repeated shelling and gunfire. Here, lacking access to markets and without regular supplies of electricity and water, operating plant has become all but impossible.

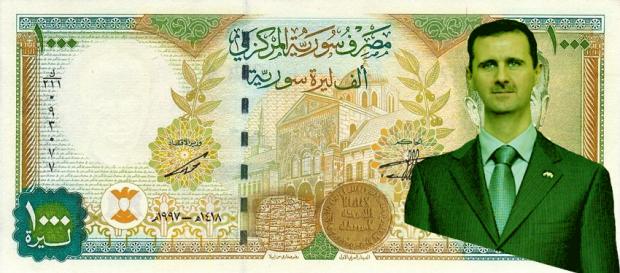

Syria’s economy has been helped by the stabilisation of the currency, the Syrian Pound, after a turbulent period in 2012-2013. Though it is a fraction of its pre-war value, the stabilisation has helped traders to plan. The Central Bank has maintained a balance between supply and demand for foreign currencies that has allowed the government to spend up to $400m a month on refining imported fuel and boosting food supplies.

The currency strengthened from a low of SYP320 to about SYP 160 in mid-2014. However, there have been recent signs of weakness, with the value crossing the SYP 200 to the dollar value. This prompted the intervention of the Syrian Central Bank in mid-November to say it would pump more than $150m to prop up the pound, though the effect has been limited.

If the Syrian government is to keep funding its bitter battle against its enemies, whether Free Syrian Army or Isis, it will need the continued support of Iran, its main external benefactor. Iran granted Syria $4.3 billion in credit facilities in 2013, and more will be forthcoming as Tehran seeks to prevent its ally from experiencing economic collapse. This cash has helped the government ensure that commodities like flour, rice and sugar have avoided sanctions – with the judicious use of front companies that are effectively funded by the government

These bulwarks will help the Assad regime to survive, for now at least. But the damage exacted to the economy from the war is substantial. The conflict has created a series of incentives for locals to prolong the conflict. According to Syrian business commentator Jihad Yazigi, as security has collapsed, an informal economy comprising looting, kidnapping, and smuggling has become an important source of income. He says entirely new business networks, often illicit, are emerging and new groups and individuals are being empowered at the expense of the traditional business class.

According to UNRWA estimates, even if the conflict ceased immediately, and GDP grew at an average rate of 5 per cent a year, it could still take Syria 30 years to return to the economic level of 2010.

That will leave a lasting and damaging legacy for Syria’s economy that will be difficult to overcome, whether the Assad regime survives or not.