Assad’s Torture Chiefs

Brian Slocock explains the Syrian regime’s security apparatus

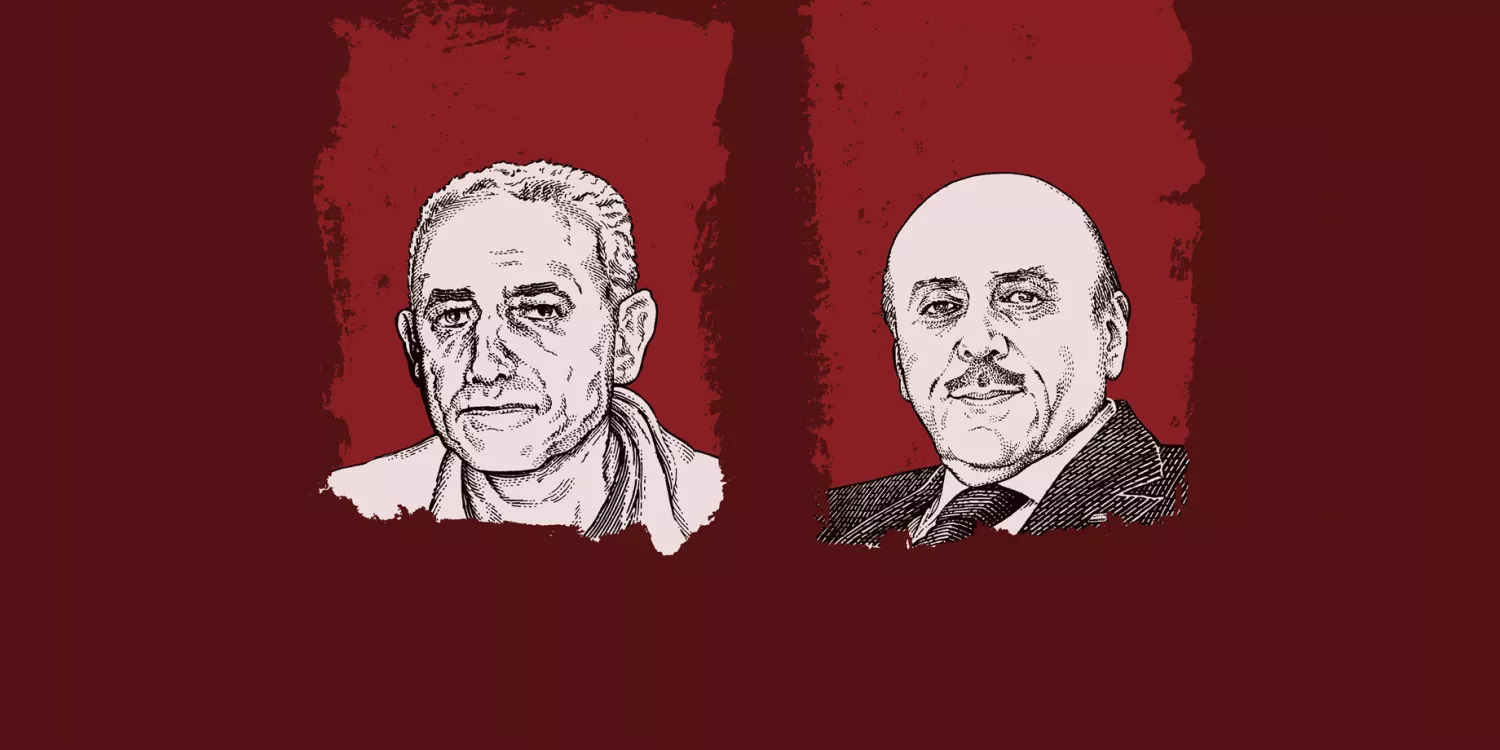

ILLUSTRATION: Lt. General Jamil Hassan, Air Force Intelligence, and Maj. General Ali Mamlouk, National Security Bureau.

The main instruments of repression and social control in Syria are the country’s intelligence agencies, known collectively in Arabic as the Mukhabarat. It is these agencies which bear the primary responsibility for the brutal repression of the 2011-2012 mass democratic movement, and the ensuing campaign of detention, torture and executions that has been directed against opponents of the regime for the past six years.

Structure of the Mukhabarat

There are four main intelligence organisations in the country: General Security, Political Security, Military Intelligence and Airforce Intelligence. Despite the names of the last two they are more concerned with internal policing than with external military matters.

In addition to these primary agencies there are a number of formally subordinate branches, which in practice operate autonomously from their parent organisations. For example, there is a powerful sub-department of Political Security named The Palestine Branch which is responsible for monitoring the Palestinian community in Syria; Military Intelligence and Airforce Intelligence each have Interrogation branches; the ruling Baath party has a National Security Bureau which plays a role in security matters; and the elite 4th Division of the Syrian army, which is responsible for the security of the capital, plays an extensive role in security operations.

Taking these into account, in total there are some sixteen agencies concerned with monitoring and regulating Syrian society.

The hierarchy of these bodies is complex, because formal status is often overridden by informal factors such as sectarian affiliation (officials from the Alawite sect to which President Assad belongs often having more power than non-Alawites of equal or higher rank in the same agency), or kinship affiliations to the Assad family (there have been many Assad relatives in the security agencies; for example, Atef Najib, the Head of Political Security in Daraa province, responsible for the abuses that sparked off the protests in March 2011, was a cousin of the President, as was Hafez Makhlouf, head of General Security for Damascus until his dismissal in 2014).

Nominally, all of these agencies are overseen by the ruling Baath Party’s National Security Bureau, but in practice agencies with powerful and well-connected Heads are powers unto themselves.

In the mid-1990s it was estimated that the Syrian security services comprised some 60-70,000 full time agents with a further 300,000 part time employees (informers and enforcers). At the time that amounted to one secret police operative for every fifty Syrians (a higher figure than achieved by the ubiquitous Stasi in East Germany, where the ratio was only one in fifty-seven. The Mukhabarat are almost certainly even larger today.

This security structure and its sweeping powers were established by the current President’s father, Hafez al-Assad after he took power in a military coup in 1970; under Hafez Assad the most powerful of the agencies was Airforce Intelligence, for the simple reason that Hafez al-Assad was an air force officer and he relied on it as his personal intelligence service.

The huge size of the Syrian secret police is a result of two factors:

- The factionalised nature of regime politics, which is contained by playing off security agencies against one another, in order to ensure that the regime is “coup proof”;

- The need to control Syrian society and stamp out any discontent. Each intelligence agency has a large headquarters in or just outside Damascus, and Political Intelligence and General Intelligence also have regional offices in each Syrian province. These are equipped with interrogation and torture facilities and detention cells.

These agencies have a pervasive presence in Syrian society: they must be notified of any large social gathering (even wedding parties) or public activities; they monitor all forms of political activity – even the political parties who support the governing coalition; and their approval is required at most stages in professional life: university entrance; entry into public sector jobs and the professions, obtaining a passport, and foreign travel. They also exercise close scrutiny of Syrian media and cultural life, and are present in the trade unions and professional bodies, and even in the Syrian Parliament.

They operate an extensive network of informers—most notoriously taxi drivers, but also hotel staff, apartment janitors, and students pressured into informing on their classmates and teachers. There is also a large cohort of thugs (who Syrians refer to as the shabiha, “ghosts”) who do the agencies’ dirty work, intimidating and attacking demonstrators, kidnappings, and sometimes killings.

Key senior personnel of the Mukhabarat

-

Head of Air Force Intelligence: Lt. General Jamil Hassan. The longest serving head of a Syrian intelligence agency, in office since 2009. Sanctioned by the European Union. In interviews he has complained that the Assad regime responded to the 2011 protests too softly.

-

Head of the National Security Bureau of the Baath Party: Maj. General Ali Mamlouk. (Formerly head of General Security, and earlier an officer in Airforce Intelligence.)

-

Head of Military Intelligence: Gen. Mohammed Mehla. (Former head Rafiq Shahadah, dismissed after being implicated in the killing of Political Intelligence head Rustom Ghazzali, was subject to EU and UK Sanctions for being ‘directly involved in repression and violence against the civilian population’ as was his predecessor Abdul Fatah Qudsiya.)

-

Head of General Security: Maj. General Mohammed Dib Zaitoun. (Sanctioned by the EU in 2011 for being ‘involved in violence against demonstrators.’)

-

Head of Political Security: Lt. General Nazih Hassoun. (Former head Rustom Ghazzali died in 2015, after a beating the hands of the bodyguards of the then Head of Military Intelligence Rafiq Shahadah, with whom he was in dispute.)

To this list we could add the following senior Mukhabarat figures who the EU have sanctioned for involvement in torture:

-

Brigadier General Muhammad Khallouf, Head of Branch 235, the ‘Palestine Branch,’ of Military intelligence.

-

Major General Nazih, Deputy Director of General Intelligence Directorate.

The role of senior security personnel is not confined to security functions. For example Lt General Bahjat Suleiman, nominally director of the ‘Internal Branch’ of General Intelligence from 1999-2005 (but viewed as the real power within the Agency) became ambassador to Jordan in 2009, a post he held until his expulsion by the Jordanian government in 2014 for his undiplomatic conduct. (Suleiman’s son Majd is the head of a large media empire with interests in Syria – where it controls a pro-regime daily – and in the Gulf.)

Planning of the repression

The Mukhabarat agencies have always been closely linked to the President, Hafez al-Assad in his time and Bashir al-Assad today. The various agency heads are appointed and dismissed at the will of the President, and they report directly to him on a regular basis. This relationship was intensified after the mass democratic protest of 2011 broke out and it was decided to organise systematic repression in response. A special Crisis Management Cell was created, chaired by a top Baath Party official and close confidant of President Assad, Mohammad Said Bekheitan, and including the heads of the Security agencies and the Minister of Defence, and attended by Maher al-Assad, the President’s brother, who is the effective head of the Army’s 4th Division. This body met and reported daily to the President, who signed off on their proposal.

Implementation of the repression

The ongoing operations of the Security agencies include the following:

-

Detentions and Disappearances

These agencies can call people in for interrogation and detain them at will, without any legal accountability. This is so common that Syrians have coined a common euphemism for it “visiting my Aunt’s house”. The only constraint on the power of the security organisations is the pervasive corruption of Syria’s state institutions: families of detainees can sometimes bribe security agents to release their loved ones, or refer them to the civil courts, where they will be released for lack of evidence.

For those not fortunate enough to benefit from this crack in the system the outcome can be fatal. They can be subject to the authority of military courts where they are not allowed any proper legal representation and can be sentenced to death.

For example, there are several young women who have been detained in Syrian prisons for years because they provided medical assistance to injured demonstrators, with the threat of a death sentence constantly hanging over them, a sentence that can be delivered at any moment and without their families even being notified.

Syrian human rights organisations have records of over 70,000 people (including over 1,000 children) who have disappeared into the regime’s prisons and detention centres, many of whom may have been executed or lost their lives through maltreatment.

The arbitrary and labyrinthine nature of these processes is illustrated by the case of opposition activist Bassel Khartabil, a brilliant software developer and prominent figure in the international IT community. Bassel was arrested in Damascus in March 2012 by Military Security Branch 215, who interrogated him under torture, and detained in Adra prison for over three years, accused of “espionage”. The real grievance that the regime held against Bassel was his standing in the outside world, which made him an influential critic of the regime’s repressive operations. In October 2015 he was suddenly transferred by the Military Police from the prison to an unknown destination and subsequently executed. His wife was only notified of his death two years later.

Extrajudicial killings and torture

Thanks to a whistleblowing defector who was employed as a forensic photographer by the security services between 2011 and 2013 we not only have evidence of the scale of extrajudicial killing being carried out by the Mukhabarat but we know which branches carry the responsibility for these deaths. Adopting the pseudonym “Caesar” for his protection, this individual smuggled a huge cache of photographs out of the country in 2014 that on examination proved to include the photographs of almost 7,000 separate individuals who had died in custody.

Of these 7,000 almost 30 per cent showed signs of torture of some form; and almost 80 per cent had been held by one of two branches of Military Intelligence: Branch 215 (Raids Branch) or Branch 227 (Damascus Branch).

Rape as an instrument of repression

Rape, threats of rape, and sexual assaults are also used systematically by the Mukhabarat in their interrogation of detainees—primarily, but not exclusively, women. After a systematic review of the evidence relating to deaths in custody, the UN Human Rights Commission reached a damning conclusion in February 2016:

“Given the above, it is apparent that the Government authorities administering prisons and detention centres were aware that deaths on a massive scale were occurring. The accumulated custodial deaths were brought about by inflicting life conditions in a calculated awareness that such conditions would cause mass deaths of detainees in the ordinary course of events, and occurred in the pursuance of a State policy to attack a civilian population. There are reasonable grounds to believe that the conduct described amounts to extermination as a crime against humanity.”