Ian Paterson destroyed my faith in doctors, but a new book has restored it

Adam Kay’s This Is Going To Hurt shows the human side of the medical profession

There are no professions more trusted than medicine. Anyone dedicating their lives to the health and wellbeing of others, enduring years of gruelling training and blood, guts and other fluids, must by nature be a caring, honest, intelligent person.

We assume our medical professionals are competent as well as caring, otherwise we'd baulk at putting our lives in a doctor’s hands, and we assume there are sufficient checks and balances in place to catch any problems early. But perhaps we assume a little too much.

The first chapter of Adam Kay’s new book This is Going to Hurt – Secret Diaries of a Junior Doctor tells me something I already knew but most people don’t: the public think that doctors are regularly appraised for competency, but they are not. It wasn’t until 2012, post-Harold Shipman, that a schedule for assessment was introduced, and it’s still only every five years. As Adam says in a footnote, “you’d be nervous about a lot of vehicles on the road if they only got an MOT every five years.” I guess the analogy falls slightly short, as doctors are more akin to drivers than cars themselves, but the general principle is the same. We treat our doctors as machines and expect them to be road-ready and well-observed, with no room for breakdown or failure.

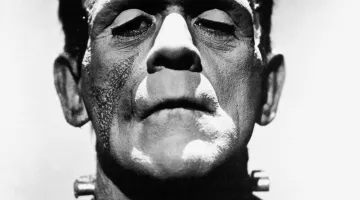

The reason I already knew about doctor competency checks is because I've been researching this topic for a while. I was a patient – victim, technically – of Ian Paterson. You’ll know him as the “breast surgeon monster” who needlessly operated on women, removing healthy breasts in some cases, or experimenting with illegal surgery techniques in others. He’s now in prison. My own operation, a lumpectomy to remove a growth in my right breast, was minor compared to the full mastectomies and multiple surgeries of some of the other women, but we are all in an unusual boat together, victims of one of the most trusted professions in the world. The betrayal is extraordinary, and it left me with a cynicism about the medical establishment and hierarchies that allowed Paterson and others like him to operate.

I’d been so angry about Ian Paterson on behalf of his patients, I'd forgotten to be angry on behalf of medicine

When my friend Adam – formerly Dr Kay – told me he was writing a tell-all book about his life as a junior doctor, I was wary that this too would be a betrayal. My cynicism kicked in because I'd built a mental wall, a “them and us” divide that had the medical profession on one side and patients on the other, and medical betrayals of any sort were more bricks in the wall. I’d lost sight of the humanity of the profession.

Adam states in his book that he wrote it to show what doctors do – or perhaps who doctors are – in the face of bad press and an unsympathetic government:

“I couldn’t help but feel doctors were struggling to get their side of the story across (probably because they were at work the whole time) and it struck me that the public weren’t hearing the truth about what it actually means to be a doctor. Rather than shrugging my shoulders and shredding the evidence, I decided I had to do something to redress the balance.”

Strangely, he achieves this not only by showing his nurturing, caring side, but by exposing his own cynicism and weariness at the system. Junior doctors, we learn, earn less than minimum wage in practical terms. Adam’s diary entry for 6 December 2004 says “All junior doctors at the hospital have been asked to sign a document opting out of the European Working Time Directive.” That week he had worked 97 hours.

“At night, the house officer is given a little paging device affectionately called a bleep and responsibility for every patient in the hospital. The fucking lot of them. The night-time SHO and registrar will be down in A&E reviewing and admitting patients while you’re up on the wards, sailing the ship alone. A ship that’s enormous, and on fire, and that no one has really taught you how to sail. It’s sink or swim, and you have to learn how to swim because otherwise a ton of patients sink with you.”

This is exactly the shot of humanity I needed to turn me back from victim to patient and pull down some of that wall. The anecdotes in the book reminded me that doctor and patient are, in the most part, in it together:

“First ventouse delivery. I suddenly feel like an obstetrician – it’s a pretty notional job title until you can, you know, actually extract a baby. My registrar, Lily, talks me through it gently, but I do it all myself and it feels great.

‘Congratulations, you did amazingly well there,’ says Lily.

‘Thank you!’ I reply, then realise she’s actually talking to the mum.”

Adam’s stories about his time as a junior doctor demonstrate how badly medical professionals are served by bad systems and rogue practitioners. I’d been so preoccupied being angry about Paterson on behalf of his patients, I'd forgotten to also be angry on behalf of medicine. For every Ian Paterson, there are thousands of deeply caring, competent medical professionals who just want to save lives or mend broken bones, and they have been betrayed too.