When I was invited earlier this year on a trip to Beirut to check out its design scene, I had few preconceptions of what to expect. The same went for Lebanon in general, a country I’ve never visited. I knew that there are successful, internationally renowned designers based in Lebanon, notably lighting company .PSLAB.

In London alone, its mainly metal and glass lighting, handmade in its factory just outside Beirut, which can be seen at Stephen St Kitchen at the British Film Institute and the Barbican Centre restaurants, Foodhall and Lounge.

Then there’s Beirut-based firm Bokja, whose appealingly colourful, one-off furniture, upholstered with an apparently random yet harmonious patchwork of vintage fabrics, and made in collaboration with local furniture makers, has been exhibited at the annual London Design Festival.

One important showcase for designers is Beirut Design Week (BDW), an annual event founded in 2012, which takes place this year from 1-7 June.

“Designers have not had a unified national platform and voice in this country for a long time, and most had to go to the Milan Furniture Fair to draw attention to their work,” says co-founder Doreen Toutikian. “BDW provides them with the necessary exposure to make them important contributors to Lebanon’s design scene. And it shares new knowledge through workshops, talks, exhibitions and a conference. We also aim to put Beirut on the global design map. Last year, we promoted seven areas of the city boasting a high concentration of designers, studios and design shops, and the event attracted more than 25,000 visitors.”

Before I went to Beirut, I approached various magazines with the idea of a story on Beirut’s design scene, but this proved tricky at first: one editor declined the idea, saying that it was a political trouble spot. As I discovered, the city has been severely affected by its proximity to Syria and its civil war. Many, mainly wealthy Lebanese, have left the country and Beirut is riddled with forlorn, half-built apartment blocks because demand for new properties has plummeted.

Lebanon’s history of instability might have constrained or stifled creativity yet, as I witnessed, it has a flourishing design and architecture community, which is at last gaining international recognition. Designers there don’t directly receive government support and are mainly reliant on not-for-profit organisations for funding.

One example is House of Today (HoT), which, funded by donors, seeks to give Lebanese designers an international profile by mounting exhibitions of their work. Pieces by Lebanese designers are also showcased by Beirut’s high-profile Carwan gallery, which participates in such fairs as Design Days Dubai, New York’s Armory Show and Design Miami.

Meanwhile, Beirut’s Académie Libanaise Des Beaux-Arts (ALBA), which has a well-regarded product design department, also cultivates talent. Several members of HoT have studied there, including Claude Missir, design duo David/Nicolas and Vrouyr Joubanian.

Yet some creatives, such as Carlo Massoud, an ALBA graduate, who designs lighting, furniture and tableware, and has shown his work with Carwan at the Armory Show, point out that designers producing contemporary work are hampered by the dearth of modern materials and technology available to them.

“Lebanon benefits from having lots of artisans and they are relatively inexpensive, compared with other countries,” he says. “But they don’t always have modern techniques at their disposal. We have wood and metals but limited access to carbon fibre, electronics and mechanical parts.”

According to HoT’s founder, Beirut-based entrepreneur Cherine Magrabi Tayeb, “We’ve always had a strong tradition of local crafts and fine materials, such as copper and marble.” One of Massoud’s designs, a light called Aladdin I, is made of traditional copper, stainless steel and walnut but is clean-lined and contemporary.

And Missir has created a double-sided, freestanding mirror that melds traditional and modern materials in the form of a marble base that incorporates a horizontal sliver of electric blue or yellow Plexiglas. The latter was displayed at HoT’s exhibition, Naked: Beyond the Social Mask, which was shown at Design Days Dubai last March.

Beirut-based designers David Raffoul and Nicolas Moussallem of design studio David/Nicolas nod to tradition with their Dualita chairs. Commissioned by upscale Milan gallery Nilufar, these reference mid-century furniture with their copper-tipped metal frames and jewel-bright upholstery.

The duo’s comparatively pared-down cuckoo clock, which mimics a birdhouse, is made of Lebanese cedar, and so riffs off their native country’s national emblem, despite looking decidedly modern.

Beirut’s design world is tight-knit. “Over the past 15 years, there’s been a sense of unity and collaboration in the design community,” says Lebanese architect and designer Annabel Karim Kassar, who creates furniture and lighting including teardrop-shaped wall sconces with a metallic, perforated surface. “And Lebanon right now is culturally stimulating. Several cultural organisations aim to develop Lebanese talent and creativity such as Ashkal Alwan, which instigates creative endeavours across a range of disciplines, and the Beirut Art Center (BAC), a not-for-profit association, space and platform dedicated to contemporary art in Lebanon.”

“The environment here can be difficult, due to lack of government support but as a result our design community is supportive, open to new ideas. The current situation impacts on our manufacturing methods but makes us more creative and resourceful,” say Huda Baroudi and Maria Hibri, co-founders of Bokja, which also has a shop based in Beirut’s Quartier des Arts, an area formerly populated by carpenters and now a hip quarter, brimming with galleries and restaurants. “We wanted our shop to be well-located but tucked away with a garden as it aims to be more than just a showroom but somewhere that encourages people to slow down and be transported from the hectic pace of the city.”

Another hindrance for the Lebanese design scene is that few people outside the country know what designers are producing. A desire to increase awareness of this was a major inspiration behind Magrabi Tayeb’s decision to found HoT in 2012. “I became increasingly conscious of the amount of talent in Beirut, and it seemed obvious there was a need to bring it to people’s attention internationally,” she says. “Our aim is to change the perception of Lebanon, to show that our design scene has its place in the international one.”

Magrabi Tayeb adds that Beirut’s design community is thriving today partly because many successful Lebanese designers are based in the city, rather than abroad: “Apart from HoT,.PSLAB, Carwan and another influential Beirut gallery, Art Factum, are all altering the way Lebanese design is perceived.”

Some believe Lebanon’s long periods of instability have made the Lebanese outward-looking, not to say tough, out of necessity. “During the war from 1975 to 1995 and again in 2006, when our airports were shut and we were evacuated to the mountains, we Lebanese have always been resilient,” says Dimitri Saddi, founder and managing director of .PSLAB. “At .PSLAB we have the attitude of most Lebanese – we live here but are always looking outside. The instability keeps you on edge, makes you think how to compete in new markets and where we’d go if something kicks off here. It ensures we’re competent enough to survive. Like most Lebanese people, we have two passports. We don’t keep all our eggs in one basket.”

That said, some established Beirut-based designers who’ve led peripatetic lives for years have since settled for good in Lebanon, creating work that is distinctly cosmopolitan. Take Lebanese-born designer Nada Debs, who was brought up in Japan, studied interior architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design in the US, set up a design company in the UK, and, after a 40-year absence, returned to Lebanon.

“My Japanese upbringing has helped me take the decorative handcrafted aesthetic of the Middle East and streamline it to create contemporary furniture. I describe my work as ‘contemporary craft’,” she says.

Her pieces include her Pebble table, which has an articulated base that allows its circular tops to be reconfigured to suit different needs. She has also designed a Floating Vintage stool which fuses tradition and modernity: an image of an odalisque in the 19th-century, Orientalist tradition is stamped on its plush, rose-pink upholstery which in turn is encased in clean-lined Plexiglas.

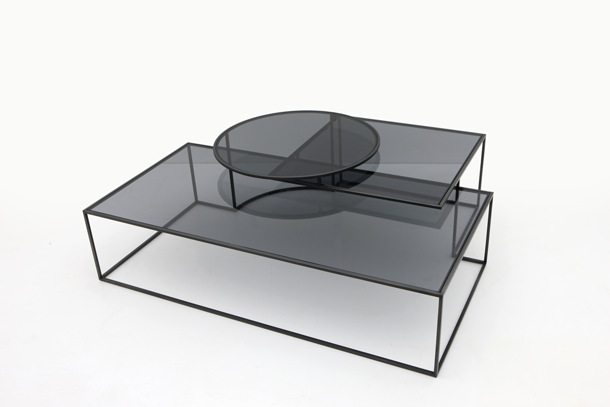

Karen Chekerdjian, who worked for years in Milan, returned to Beirut in 2001, where she founded her eponymous studio. In 2010, she opened Karen Chekerdjian Store, a showroom selling her work in Beirut’s port area, and today exhibits at the Milan Furniture Fair and another design event, ICFF in New York. She sums up her work as “industrial handicrafts” – a reference to its industrial aesthetic, which renders her hand-made, limited-edition pieces reminiscent of mid-century design. These include the curvilinear Papillon chair, Living Space III – a foldable seat-cum-coffee-table-cum-magazine rack – and Hiroshima light.

Given the multicultural backgrounds of some of Lebanon’s key designers is it possible to talk about a specific Lebanese aesthetic or approach to design? While this can lead to generalisations or stereotyping, some observations can be made, however: undeniably, designers seem to favour both natural materials and the more slick, artificial look of Plexiglas, often in punchy, neon-bright shades. A few designers, such as Debs and Kassar, have a predilection for decorative Islamic geometric patterns.

Yet some are sceptical about pinpointing a Lebanese style: “If it were possible to talk about a Lebanese aesthetic, it would focus on crafts,” says Massoud. “But because of such diversity within the design community, I’d struggle to describe an overall style.”

“I’ve tried to define ‘Lebanese style’ but it’s not easy as we’re a mix of cultures, religions, lifestyles,” says Debs, who showed a retrospective of her work at Design Days Dubai. “I’d say we try to mix different styles to come up with something on-trend. Also, our designs reflect who we are: we Lebanese are emotional people and this is reflected in our designs, which evoke a feeling of nostalgia but also of modernity.”

Dominic Lutyens was a guest of Beirut’s Phoenicia Hotel (www.phoeniciabeirut.com)