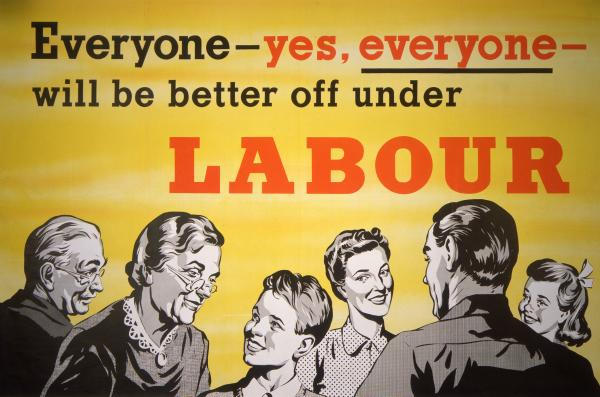

There is a new left-wing political party in Britain which, for now, is called the Labour party. It may carry the name "Labour", the blandly fonted red logo and a set of MPs, many of whom were elected while Tony Blair was Prime Minister, but this is not the Labour party you know. For decades, the British left has fantasised about creating a new political movement - well, it's happened and will transform British politics for a generation.

When I was selected as a Labour councillor in Lewisham in 2009, my local party had 80 (mostly quite old) members. 6 people turned up to the meeting where I was selected. Probably no more than 4 people decided I was one of the best candidates to represent 18,000 people in one of the most diverse places on earth. Hardly democracy's finest hour. Since the time of the Iraq war, the local party had pretty much been defunct, with few active members. For many years it had no local meetings at all.

Now it has nearly 250 members, almost all of whom have joined since Labour lost the 2015 election. These new members are young, diverse and will in all likelihood vote for Jeremy Corbyn to lead the Labour party. As someone on the right of the party, it isn't false modesty to suggest that my chances of being selected by these new members would have been pretty slim.

Labour now has 610,753 members, supporters and affiliates. A staggering 1 in 15 people who voted Labour at the last general election will be able to vote in Labour's leadership campaign.

From a low of 176,891 members in 2007, membership has nearly doubled to 299,755.

Any political party is the sum of its members – they knock on doors to convince voters, they select candidates for the council and MPs, they arrange the meetings, the cake stall at the local fair and fundraise for the party. An entirely new membership will create an entirely new party.

The impact will be profound. The punditry imagine that if one of the anyone-but-Corbyn candidates wins, order will be restored. It's too late. Across the country, MPs should be nervously assessing their chances of being deselected by new members who didn't vote to select them in the first place. You have to wonder how long the last remaining Blairite MPs have left. If Corbyn is leader, he will argue for the mandatory re-selection of all MPs. The parliamentary Labour party could look very different by 2020.

Party conference season will be different too. Corbyn wants Labour party conference to decide on the party's policy (as it did in the past). Out go the grey men in suits presenting "The future of banking by Snore Bank Ltd". instead we'll have chaotic public arguments over nationalisation. Labour's fundamental arguments – over public versus mutual or private, our foreign policy, defence policy – arguments that have beset the party with division in the post-War period will be held naked before you. It is going to be messy.

The question is: how much of this can the public stomach? Will the sight of arguments on the conference floor and torrid, highly personal de-selections convince the British public at large that Labour is in such a state it can no longer be trusted to govern? Or will they rejoice at the end to robotic managerial politics – the safe politics which saw the Labour party enter the 2005 general election with the slogan "Forwards Not Back" (perillously close to the parody campaign slogan "forwards, not backwards, upward, not forward; andalways twirling, twirling, twirling towards freedom!" which appeared in season 8 of the Simpsons)?

This isn't just a question of Corbyn's character, but a wider question about the future of politics in Britain. The Tories will not be immune from the urge to make their party more open and democratic. The public may well decide whether they will punish the Tories if they choose not to do so.

Fundamentally, the right of the Labour party is stuck in a political time warp. Obsessed with Tony Blair, a man who has embarrassed himself since leaving office through his advice to the dictator of Kazakhstan and speeches in unfree Azerbaijan, it has failed to create a politics of hope. Liz Kendall has said some incredibly brave things on civil liberties (including rolling back on state surveillance) but Labour members are no longer listening.

The average Briton is 40 years old, with 1997 the first general election in which they voted. They simply do not remember or care about the Militant Tendency or the Bennites. They do remember Iraq and the MPs expenses scandal, the shadows of which loom large over the parliamentary Labour party.

The young voters inspired by Corbyn care little for arguments over the 1980s and Thatcher. Like in Scotland, the electorate demand a sense of hope. That Corbyn is the tribune of that hope is, well, unfortunate. A kind but flawed man who has little to say about human rights abuses in Venezuela and Cuba (or worse, refers to psychopathic terrorists Hamas as "friends") while favouring punishing tax increases is going to find it hard to win a general election. No matter how many times it is said that over half the electorate voted for parties of the right, Labour’s leadership debate continues to veer to the left. In the meantime, throw away all your assumptions about the Labour party.

New MPs, new members, a new leader and a new policy platform. This is either the beginning of the Labour party or its end.