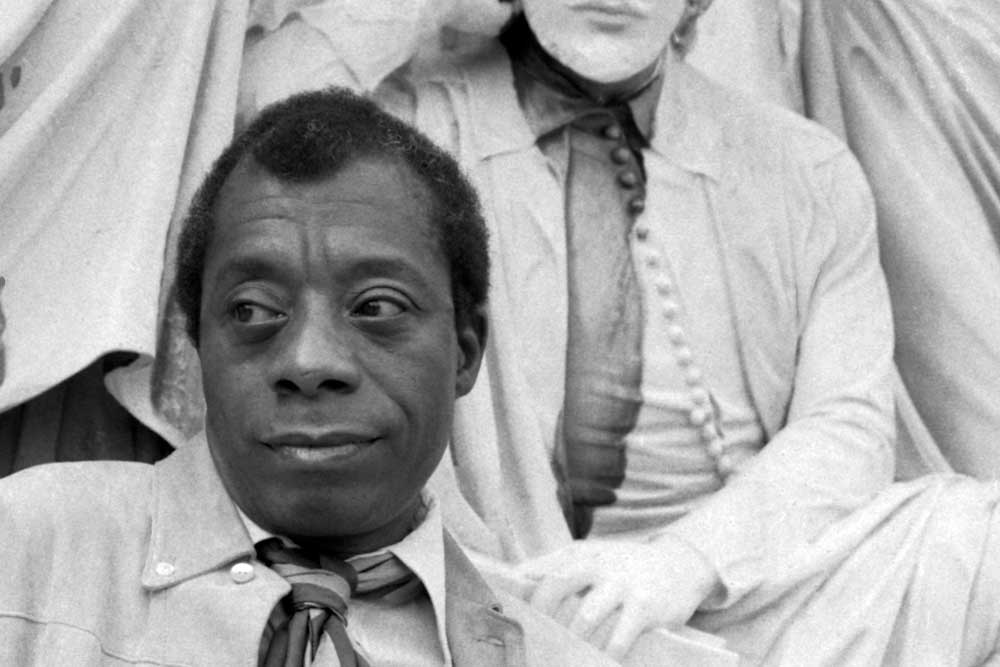

I’ll always remember the mind-expanding moment when as a younger man I watched footage of James Baldwin, cigarette in hand, looking down the barrel of a camera and patiently, but firmly, informing white Americans that the so-called “Negro problem” was one of their own invention:

“I’ve always known that I’m not a nigger. But if I am not the nigger, and if it is true that your invention reveals you, then who is the nigger? I am not the victim here. I know one thing from another. I know I was born, I’m going to suffer and I’m going to die. I know that the only way you can get through life is to know the worst things about it. I know that a person is more important than anything else – anything else. I’ve learned this because I’ve had to learn it. But you still think, I gather, that the nigger is necessary. Well he’s unnecessary to me, so he must be necessary to you. So I give you your problem back. You’re the nigger baby, it isn’t me.”

Here we see Baldwin’s talent at its symphonic best – he could rearrange your insides with a few words of disarming honesty. The insight quoted above forms the nucleus of I Am Not Your Negro, an incredibly powerful new film by director Raoul Peck, based on Baldwin’s notes for a book on the civil rights movement and its three slain leaders, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

That book, Remember This House, was never completed – Baldwin died of cancer in 1987 – but Peck fleshes out the notes with the rest of Baldwin’s published work on the period and its main players, all of whom Baldwin knew personally.

The film’s weaving of historical footage, blues and jazz music and street sounds overwhelm you from its first moments, and place you smack in mid-century Harlem. The clips of Baldwin’s speeches and interviews are well-chosen. Baldwin’s ideas and delivery are powerful enough in themselves, but the context in which Peck places them reveals their true weight, and leaves you at their mercy. (I challenge anyone to watch I Am Not Your Negro in the cinema without crying at least once.)

The film is narrated by Samuel L Jackson reading Baldwin’s words, as arranged by Peck, in what is simply one of Jackson’s finest acting performances. The word “arranged” however is the right one. I Am Not Your Negro is a composition, or an essay in film, and while the words might be Baldwin’s, the author is undoubtedly Peck. What is Peck saying in the piece? Well, it’s clear from his introduction to the transcript of the film that Peck shares with The Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates a strong case of Baldwin-itis, and the film is partly Peck’s attempt to do justice to a man he reveres.

It’s not difficult to see what Coates and Peck find so attractive in Baldwin. It’s the power and delicacy and honesty of a novelist, elevating their own experiences to those depicted by Henry James or Charles Dickens, to name two of Baldwin’s favourite authors.

What’s involved here is not merely seeing yourself represented in popular culture, important though this is. The measure of a novelist is their ability to reveal in the specific that which is universal. The novelist who writes about being black in America, if successful, writes about you as part of the human race, (the only race there is), and therefore just as valuable and complicated as a Hamlet.

Novelists also have a gift for getting speech onto the page, breathing life into their prose and crafting it into tight units of emotional truth. This is the secret of Baldwin’s rhetoric and writing – its power is that of prose reaching towards poetry. It’s a shame Baldwin’s fiction is largely absent from the film, as is his writing about sex – a central part of his work, and for Baldwin the dirty secret of American racism, which he saw as related to the Christian concepts of purity and sins of the flesh.

Baldwin is alone among his contemporaries in being mostly free of ideology, after brief stints as a junior church minister in his teens and later as a socialist. While this certainly liberated him as a writer, it also takes him outside politics, making him ripe for appropriation.

This brings me onto the great mark against I Am Not Your Negro, praised in the New York Times and the Guardian under the guise of “relevance”. In a few key sections in the film, Peck decides to cut from protests and police violence in the 1960s to footage of protesters in Ferguson, Missouri, after the death of 18-year-old Michael Brown in August 2014.

As Jackson/Baldwin continue their husky description of mid-century America, we are shown the infamous footage of cab driver Rodney King being beaten by a gang of Los Angeles police officers in 1991, or photographs of the young black victims of police shootings and other atrocities from recent years.

In an interview with the Guardian in February, Peck said he wanted to “remind people that this man [Baldwin] has given us all the instruments we need already”. Press notes for the film state baldly: “Whilst it is partly anchored in the struggle for equality in the 50s and 60s, I Am Not Your Negro is about what it means to be black in America today.”

It’s one thing to say we can gain insight into the present by reading a brilliant writer from the past. It's quite another to suggest or imagine that he can provide us with “all the instruments we need” to understand his own time, let alone ours. And I invite you to consider whether any other social issue could seriously be said to have changed so little in half a century.

In this way, Peck’s film proves itself to be a product of its time. There is right now a growing tendency in popular thought to say that “nothing has changed” in America since the days of segregation and lynchings, and that a single and simple analysis can hold true across time. The election of Donald Trump as president on the back of white resentment has put wind in these sails, and not only in America.

This trend can be found in a recent spate of Hollywood films – 2014’s Oscar-nominated Selma chief among them – which portray the history of black Americans essentially as a struggle of prejudice versus strong black individuals. (In reality, the only progress which has been achieved was the result of organised mass movement politics). Peck’s film, for all its merits, falls into this ahistorical and politics-free category, and would do so even if the Ferguson references had not tipped his hand.

Any attempts to co-opt Baldwin for contemporary use are doomed to failure by the man’s fierce and feline independence. At his best, Baldwin never allowed himself or anyone else a consoling myth, and suspected those offering easy solutions to the world’s problems. He was a true American patriot, trying to save his country from itself, and this meant telling his fellow countrymen and women of all “colours” truths they might not wish to hear.

He recognised that each human life is complicated and precious, and deserving of liberty and security. In his penetrating work on American ideology, Baldwin stressed that the power of ideas is born of social conditions. (The Fire Next Time was written as a warning about where those conditions would lead.) But when those conditions changed, he changed his mind, rather than holding on to the same analysis for comfort. Above all, Baldwin implored people to face the past, the better to understand and change the present. If those levees break, we won’t know where we are. Whatever his intentions, Peck’s great tribute to James Baldwin is to have made a film about him describing his own time, and not ours. He was a witness, not a prophet.