Uzbekistan's government is so keen to control social media, it has launched its own network. Inga Sikorskaya reports

Uzbekistan's government is so keen to control social media, it has launched its own network. Inga Sikorskaya reportsThis article is published in association with IWPR

The launch of yet another state-run social media site in Uzbekistan has served to highlight Tashkent’s contradictory approach to regime control of the internet.

Over the past 15 years, online access in Uzbekistan has soared. As of November 2015 there were 12.7 million users out of a population of around 30 million, compared to 7,500 users in 2000, according to Internet World Stats.

The government has been largely supportive of this growing internet access. Tashkent acknowledges that increased internet penetration has helped expand the economy, especially the small business sector.Online shopping is also growing in Uzbekistan, facilitated by home-grown e-payment systems.

Nonetheless, some news sites and critical media remain blocked. The regime views the proliferation of networking and content-sharing sites with particular suspicion.

Uzbeks, it turns out, are especially fond of social media.

Market researchers J'son & Partners estimated that the number of social network users in Uzbekistan grew by 40 per cent a year between 2010 and 2014, the highest rate in the entire post-Soviet space.

In response, the government has created no less than Uzbek 38 networking sites, although only eight of them are currently operational.

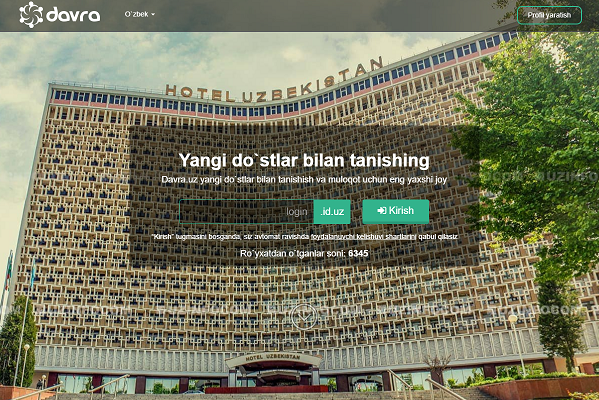

The latest addition is Davra.uz, officially launched on 1 June and offering photo and video sharing as well as discussion groups.

Developed by Uzinfocom, a state-owned IT development centre, with support from the Information Technologies and Communications Development Ministry of Uzbekistan, Davra gained nearly 6,000 registered users within its first week of operation.

Of course, local networks such as these cannot compete with their massive international counterparts.

According to independent US-based online market research company Internet World Stats, Uzbekistan has 450,000 Facebook users. At least 900,000 Uzbeks use the Russian social network Odnoklassniki.

Uzbek social networks provide the perfect advertising platform for local business, used as they are mostly for e-commerce and information about fashion and culture.

But they are also seen as a useful way for the state to try and lure social media users away from foreign networks to local alternatives where it is easier to monitor and control them.

The most popular Uzbek social network, Muloqot.uz, currently has more than 170,000 users.

Registration is compulsory to access this service. Although Muloqot’s user data is securely encrypted, its servers belong to state communications provider Uztelecom.

It’s a simple matter for Uztelecom to track users’ IP addresses when they register on local networks.

Young Uzbeks prefer to use Facebook and Russian social networks for private messaging, even though they’re aware that these platforms are not secure either.

Still, they provide a window to the world and an alternative source of information.

News outlets such as Ozodlik (RFE/RL), the BBC Uzbek service, Voice of America and Fergana.ru have been blocked for around the last ten years, and much of the content on Uzbek news sites is little more than government propaganda.

As well as spreading patriotic messages derived from the public speeches of President Islam Karimov, online media is full of attacks on any suggestion of nonconformity.

News pieces regularly demonise NGOs, human rights defenders, independent journalists and other groups regarded as anti-Uzbek agents of western influence.

While Uzbekistan’s autocratic government has long focused on blocking independent media and spreading patriotic messages, this focus on the online space is fairly recent.

It was only following the Arab Spring of 2011 that Uzbekistan really began to strengthen its monitoring efforts.

In early 2011, users of online forums in Uzbekistan began discussing the protests in the Middle East and North Africa – only to find access to pages with news from the region summarily blocked.

Local forum Arbuz, one of the country’s most popular discussion platforms, was temporarily blocked in mid-February 2011 after users began discussing the uprisings and criticising Uzbekistan’sown political and economic situation.

Access to the forum was subsequently restored, but sections on domestic and international politics were removed. By December 2011, Arbuz’s owners shut it down for good, fearing more problems with the authorities.

The government then rolled out a campaign denouncing the internet as a “destructive force” against which “a coordinated fight” must be waged.

In a move that was interpreted as a surveillance attempt, Uztelecom blocked Skype and Viber voice calls from late 2014 until October last year, leaving users with only the messaging option. The communication provider claimed that the service was unavailable due to routine network improvement.

But the Uzbek authorities have learnt that simply blocking websites had only limited success. Local users have picked up various technical tricks to out manoeuvre cyber censorship, from proxy servers to using VPN and TOR browsers to access blocked sites.

With mobile internet use also growing, securely encrypted cloud-based messaging apps are increasingly popular among young Uzbeks.

And the wide availability of free VPN apps mean that blocked news providers such as Ozodlik are using social media to spread their content.

It’s not just affluent city dwellers using these technological tricks; the huge student population as well as activists in the region are well aware of how to slip past the censors.

Nonetheless, self-censorship has become standard practice for the average Uzbek, even among those who are not particularly politicised.

Social network users are reluctant to leave public comments or “like” any posts that might be perceived as critical of the regime.

Even though Facebook and Russian networks are not blocked, in Uzbekistan one gets a feeling the state is constantly present, sitting right next to you while you’re surfing the web.

The huge state apparatus still wants to control people’s lives both online and offline.

It’s clear that the attempt to create numerous Uzbek alternatives to Facebook is intended to be another tool in the state’s armoury of surveillance.

In Tashkent, people have long said that that the only way to make sure a conversation remains private is to speak face-to-face in the city park or behind closed doors.

Online, the state’s intrusion remains as present as ever.

Inga Sikorskaya heads the School of Peacemaking and Media Technology in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. She previously served as IWPR editor for Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan.

This article was produced under an IWPR project called Strengthening Capacities, Bridging Divides in Central Asia, funded by the Foreign Ministry of Norway.