A call for submissions for The Works of Elena Ferrante: History, Poetics and Theory, a volume edited by American academics, expired a couple of weeks ago. The New Yorker has just written its umpteenth article on the Neapolitan novelist, calling her “a genius” and a “titanic novelist”.

Meanwhile in Italy the elusive writer has been dragged into the mire by part of the Italian literary establishment unable to cope with a woman whose impressive success at home and abroad is not matched by any desire to be in the limelight.

Elena Ferrante’s ability to speak to a wide public all over the world is unparalleled in Italian history. When her name was put up for the shortlist for the prestigious Premio Strega award, someone suggested she should first reveal her real identity, notwithstanding the fact that she had already been an (anonymous) contender for the prize back in 1992 with her debut novel Troubling Love. Then a wolf pack of male intellectuals took pleasure in diminishing her literary qualities, comparing her to lightweight pop romance novelists and relying on a staggeringly misogynist narrative which would sound completely misplaced anywhere else.

Let’s take some examples. In one case, a respected literary editor suggested on his Facebook account that Ferrante should go and “tidy up” a male rival’s apartment; in another case a critic on the broadsheet daily La Stampa compared her to a piece of “software that produces stories” who owes most of her fame to the hype created by her anonymity.

Her success, he wrote, is “disproportionate”, her answers in interviews “pathetic”, and the plot of her novels are similar to those of a “soap opera”. The fact that Ferrante’s works are celebrated in Anglo-Saxon countries provided this and other critics with “evidence“ that her prose has only commercial appeal and no real literary value. This is added to the other charge against Ferrante: her readership is mostly female – proof of how worthless her work is.

Elena Ferrante’s fans, male and female, share their favourite writer’s penchant for discretion. They seem to have decided not to fight back against her accusers, reiterating their absolute worship of her novels, with which many readers have developed a very emotional personal bond.

But success like Ferrante’s cannot be ignored by cultural institutions. Fellow Neapolitan writer Roberto Saviano wrote a piece for La Repubblica suggesting she should be shortlisted to the Strega prize, Italy’s most important literary award. Ferrante accepted his endorsement in a public letter in which she also openly confronted the blood-thirsty literary establishment “dominated by friends of big publishers”. There was a vengeful undertone to her words – “If My Brilliant Friend won’t even be shortlisted, following the usual procedure, we will be able to say, without any doubt, that the Stega Prize as it is is not reformable and should be thrown in the air,” she wrote. For a moment she sounded human and less aloof than usual. Would she be tempted to follow this path and debase herself by joining one of the rowdy and pointless debates which have become one of Italy’s most persistent features? She didn’t do it, to everybody’s relief.

In today’s noisy Italy, detachment has become a value in itself. The novelist’s elusiveness is just as endearing as her unforgettable characters Lenù and Lila and as intriguing as the unfolding of their strong friendship set against Italy’s recent history.

Ferrante’s personal story is a Mediterranean fairytale in the same way that JK Rowling’s ‘rags-to-riches’ story epitomises success in the Anglo-Saxon world. She is the introspective writer whose very personal style leads her to worldwide fame while leading a normal life in her hometown, Naples, away from the spotlight. She is the heroine who seems to have avoided the inexorable fate of Southern Italians: compromise. This may or may not be true but it’s now part of her aura and what her readers love in her. For that reason the Strega controversy sounded so wrong.

Her four novels – she calls them The Friend, as if there was only one – provide among other things an accurate dissection of the role that compromise plays in life, particularly in Naples, a city which still provides much of Italy’s narrative material and where many of the country’s most significant writers are from.

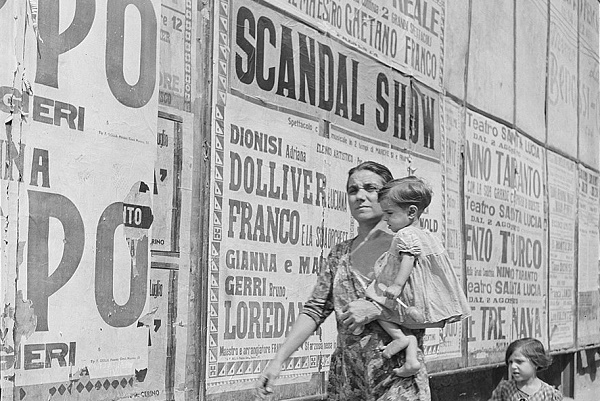

This is not surprising. Naples’ beauty and backwardness are an interesting context for characters to evolve, in particular for two women challenging public morality, religion and male domination. The same atmosphere can be found in both Anna Maria Ortese’s The Sea does not Reach Naples, or, more recently, in Valeria Parrella and Domenico Starnone’s excellent novels. The latter, oddly enough, is married to Anita Raja, a sixtysomething translator of Christa Wolf and other German literature. Credible rumours suggest that Raja is the real Elena Ferrante.

Does that change anything? In a recent interview in the Paris Review Elena Ferrante typically doesn’t reveal much about herself and gives very considered answers, suggesting that her reluctance is a natural feature and not a pose. She comes over as slightly younger than her characters, incredibly well-read, more timeless than old-fashioned and the kind of lady you would find reading avidly under her parasol on the beach, or a woman with inquisitive eyes you might meet in the library she is said to run in Rome.

Her answers suggest the analytical brain of a scrupulous reader, and one can only wonder where her knowledge of the paralysing emotional dismay she describes in her first novels comes from. So in the very moment in which her identity is being revealed, she relies on the ultimate protection: being utterly uninteresting.

Italy’s wildly aggressive reaction to Elena Ferrante is worth examining. Maybe what provoked it is not just misogyny, thought that is certainly a growing phenomenon in Italy’s cultural and political environment. It is often said that attitudes towards women in modern Italy were shaped by former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi’s fondness for scantily clad young ladies, by the need for commercial TV to appeal to its audience by showing female flesh, by a society which still remains quite traditional and where female unemployment is sky-high.

This may all be true, but Ferrante’s case is telling in that it takes place in the very same milieu that rejected the Berlusconi narrative. Among the Italian intelligentsia it seems it is acceptable to say that a successful female writer should go and “tidy up” a male rival’s apartment.

Admiring the international successes of Italians is not a given either, as shown by the fierce critical reactions to Paolo Sorrentino’s film The Great Beauty (again a Neapolitan author) when it won the Oscar. Personal tastes matter, of course, but, for a country which has been flirting with total irrelevance for some decades now, good news should be taken as such. It is not.

This leads to what could be the real reason behind the strong feelings of Italian intellectuals towards Elena Ferrante. The second question raised by her rather uninteresting persona concerns her relationship with contemporary Italy.

She published her first book in 1992, a pivotal year for the country. This was when inquiries into corruption transformed the entire political system. A dramatisation of these events, simply called 1992 is currently being broadcast in Italy. Nostalgic as it sounds, it is successful.

People are talking about it; they like to think about a past which was surely more promising than the present.

In the last 23 years Elena Ferrante went from the acerbic Troubling Love to the impressive The Lost Daughter. She changed, matured, evolved, and succeeded while remaining herself. She kept her promises. This could be hard to forgive in a country which has not even started coming to terms with its lost two decades.

Time was wasted debating irrelevant topics, and in the meantime Italy became poorer, more conservative, lost large chunks of its cultural prestige, saw the new generation emigrating abroad and remained stuck in the past. A silent woman in Naples did exactly the opposite.