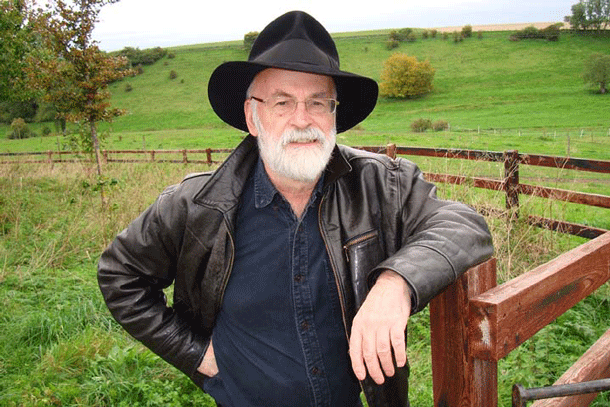

The first time I met Terry Pratchett I was in my early teens: he patiently signed every volume of my complete Discworld collection. When I met him years later in my professional capacity at the British Humanist Association, he didn’t recall that occasion or my Discworld T-shirt.

As well as being firmly in the category of “national treasure” and the best-selling British novelist of the 1990s, Terry Pratchett was a great humanist and a stalwart supporter of the BHA.

His humanism showed itself in his work in many ways. When asked for an example of this himself, he cited his story The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents, in which the mice invent morality before they invent religion. That summed up Terry’s view on morality and religion. Morality came first: it was a natural development of society. He did not see ethics as coming from outside of human beings, but instead from the bonds we shared and as a product of human beings living cooperatively together and trying to promote happiness.

Over the last 20 years, he expressed these views on humanist values in many video resources we produced for schools. His voice was one that always appealed to young people. Seeing these resources used in classrooms, you realised what a compelling communicator Terry was – not just a great story-teller, but a great intellect capable of putting a human face on complex responses to big questions.

He was a human face on many humanist campaigns as well. He joined in our lobbying against faith schools on many occasions, signing letters to press and politicians. His campaigning zeal did not dim with advancing illness. Last year he was a signatory to the open letter to the Prime Minister calling time on the damaging description on the UK as a “Christian country” – an initiative which inspired weeks of national debate about secularism and national values. He also contributed a powerful witness statement to the BHA’s submissions to the Supreme Court in the assisted dying cases of Tony Nicklinson and Paul Lamb. Both Tony and Paul were paralysed and wished to end their suffering, and Terry was deeply moved by their plight. In his submission, Terry said: "Either we have control of our lives, or we do not."

In 2013, when he was named Humanist of the Year, Terry was too unwell to give the acceptance speech himself and so the words he had written were read for him. There was hardly a dry eye in the hall as we all listened to his passionate plea for assisted dying for the incurable suffering, and resounding laughter as he described first reading of Charles Darwin’s The Descent of Man with measles and hallucinations as a child, or his rational father’s belief that he should take care of repairing motor cars and the universe could take care of itself. It illustrated why Terry was such an asset to humanism: we have philosophers and scientists a-plenty but storytellers who can make you laugh and cry on a human scale are rarer.

Terry will be missed by all of us who worked with him, and our thoughts are with his family and friends at this time. Terry didn’t believe in heaven or an afterlife, but he surely believed in immortality of a sort: the immortality of great writers. He will undoubtedly have some portion of this himself. As he said, “No one is actually dead until the ripples they cause in the world die away.” As a campaigner, thinker, and creator of worlds, Terry Pratchett will live long.