There are no protests outside the Emmanuel Centre in Westminster, London, when I arrive. There have been no petitions, and no angry pleas for the venue to cancel the event I’ve come to see: a two-day conference called “The New Normal: Tackling Sexuality and Gender Confusion Amongst Children and Young People”, put on by conservative campaign group Christian Concern. The quiet is unsettling. Any discussion of transgenderism that goes beyond the affirmative now tends to attract extreme hostility.

In Canada, a doctor has been fired and his clinic shut down under pressure from trans activists. Feminists who hold that sex is more politically relevant than gender identity are accused of causing violence against trans people. The organisation Radfem Collective, which has been attacked as trans exclusionary for its women-only attendance policy, now doesn’t reveal the location of its conferences until the day before the event – sensibly, given that pressure from protesters over another women-only event in 2012 led to the venue pulling out and the event being cancelled.

The New Normal outstrips any of these targets. It features, among other things, an “ex-gay” counsellor who claims he can guide his clients out of “unwanted same-sex feelings”; a former Ukip parliamentary candidate who claims that homosexuality is connected to pedophilia and bestiality; and two speakers who describe themselves as “COGs” (short for “children of gays”), and claim that same-sex parenting is a violation of children’s rights. There’s also an honest-to-goodness “conversion therapist” who claims to be able to counsel gay people into straight behaviour. Christian Concern itself is currently providing legal support for a mother and father who could lose custody having refused to acknowledge their trans child’s gender.

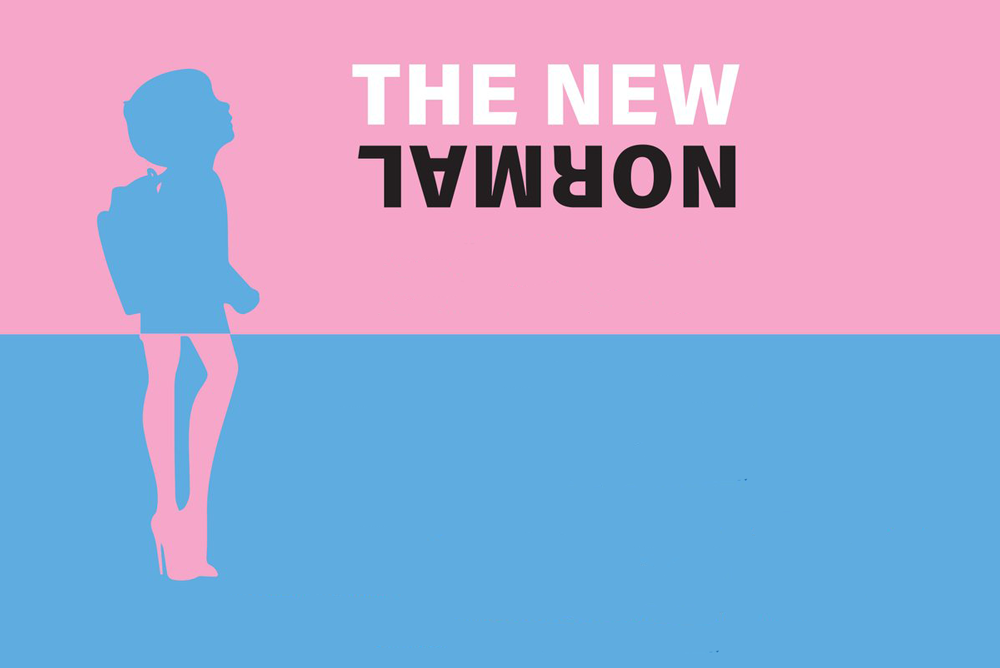

Even the branding of the event is a hostile takeover of the colours of the transgender pride flag, designed in 1999 by activist Monica Helms. For Helms, the powder blue and baby pink symbolised the traditional colours for boys and girls; for Christian Concern, the symbolism is the same, but the colours are remorselessly bound to physical sex. On the cover of the programme, a boy’s silhouette in blue on a field of pink is sliced at the waist and joined with a pair of sexy women’s legs in pink on a field of blue. Inside the programme, male panellists’ details are printed on a blue background and female ones on pink. Even my name tag is pink. Clearly, no “gender confusion” will be allowed today.

The night before, I was five minutes away at the Channel 4 building, and in an entirely different world, at a screening of Kids on the Edge. Episode one of this documentary series on child mental health follows two patients of the Tavistock and Portman gender clinic, one male and one female. Watching footage of the male child expertly applying makeup, someone besides me calls out “oh, she’s a girl!”. In the Q&A afterwards, the mothers of the two children talk fluently about the separation between gender and sex, and the right of children to “decide who they are” – up to and including hormone therapy to prevent puberty, which both families ultimately opt for. There’s a sympathetic murmur when one mum describes her child’s sex as a “defect”.

“Even the branding is a hostile takeover of the colours of the transgender pride flag”

If you listen closely to the documentary, you might notice some underlying tension. During one of the interviews in the documentary, lead clinician Dr Polly Carmichael says: “In some senses, culture and society are moving faster than the evidence base, in terms of what they understand about it [gender identity], and what they should do about it.” In other words, the world outside the clinic has a faith in the diagnosis and treatment of gender identity that the actual practitioners cannot share. This subtle note of caution, however, doesn’t puncture the mood in the screening room.

If the doctors who treat gender are feeling out of step with public opinion, the deeply conservative audience of The New Normal ranges between baffled and embattled. One attendee tells me that she just wants to get some ideas for working with the young people in her youth group when they present themselves to her as trans; a father I speak to, meanwhile, tells me that his children seem to come home from school “every day” with a new story of Christians being persecuted for being Christian. I think of the picket-free street outside, and the openly advertised venue, but say nothing.

This sense of being under threat, though, is a useful one. Andrea Minichiello Williams, the head of Christian Concern, introduces the panel by saying that all have been victims of “hostility and punishment”. The keynote speaker, Robert López of the Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, explains that he was pushed out of his job at California State University by “liberals… free-thinkers… homosexuals”. He encourages listeners to infiltrate cultural and academic institutions in order to spread their message. Julia Gasper, now of the nationalist English Democrats, was expelled from Ukip for her homophobia: listening to her announce that “gays are paedos” and “lesbians hate men”, I feel an unusual sympathy with the party of Nigel Farage.

But learning the lessons of identity politics, and seeing themselves as a resistance, is an important strategy. Williams (who is a barrister) mentions the possibility of convincing courts to treat “ex-gay” as a protected characteristic like sexuality or gender reassignment. And as Stephen Green of conservative campaign group Christian Voice says during the Q&A session, his original vision for Christian Voice was that “Christians could do the same as the gays”.

“The Bible never teaches us the soul is gendered, our body gives us that sense”

At the Channel 4 screening, one of the mums explained that she was unsure about grouping her trans child with of the LGBT movement “because it’s a sexual category”, and she considered her child too young to have formed a sexual orientation. Increasingly, trans status is presented as separate from sexuality: as one well-worn phrase has it, “gender is who you go to bed as, sexuality is who you go to bed with.”. In the Emmanuel Centre, though, this careful distinction is almost entirely absent. For all the pink and blue branding, most of the rhetoric is simply anti-gay and anti-lesbian, with transition largely understood as a kind of “extreme gayness”.

Only one of the morning’s speakers offers a specific critique of gender identity. Carys Moseley, who the programme says is “a researcher who seeks to bridge Christian scholarship with the needs of churches” (she also works for the Presbyterian Church of Wales), starts from the position that “children have a right to grow up male and female as God created them, and the purpose of that is marriage”. But obviously, such a statement doesn’t rule out transition itself, only relationships between same-sex couples. Her Biblical case against transgenderism comes down to an argument about souls, and whether they can preexist the body – or have a gender at all.

The doctrine of the preexistence of souls is considered heretical in most branches of Christianity, but, argues Moseley, “it lends itself to the belief that the soul is gendered and God mixed up some souls in the wrong body.” The typical formulation to describe gender dysphoria – the “born in the wrong body” narrative – is, for Moseley, a claim to have a soul that existed prior to the body and has a gender that can countermand the body’s sex. It’s not the idea of ensoulment that she objects to: it’s the specific qualities that the soul needs to have to make this claim compatible with trans identities. “The Bible never teaches us the soul is gendered. Our body gives us that sense,” she says. In other words, trans doctrine requires a belief in souls – and the wrong kind of souls at that.

But what if you don’t believe in souls at all? It’s hard to imagine that everyone warmly applauding Kids on the Edge the night before was an avid adherent of Christian heresies. Yet, unless you’re willing to engage in some of the messier explanations for gender dysphoria, accepting that the inherent self can have a different sex to the body means believing in a brain-body split. If a girl can be “born in a boy’s body”, it suggests that each of us has some kind of immaterial essence, and that this immaterial essence has a gender.

In the trans flag that appears as in the programme, pastel blue and pastel pink are there to represent masculinity and femininity, and to make a statement about the naturalness of those conditions. For Christian Concern, being born female means you should properly develop to be a feminine person. For the approving audience of Kids on the Edge, the feminine behaviour of a male child was obvious evidence of that the child was, in some profound way, female.

The hostility of Christian Concern to gay and gender-nonconforming children, and its commitment to “correcting” them, should not be underestimated: the approaches it espouses are cruel and homophobic, its models of manhood and womanhood limited and absurd. But in that overlap of colours there’s an important question about just what, exactly, we’re professing to believe when we dodge complex understandings of being trans and settle instead on a simple acceptance that a functioning body can be a congenital defect.