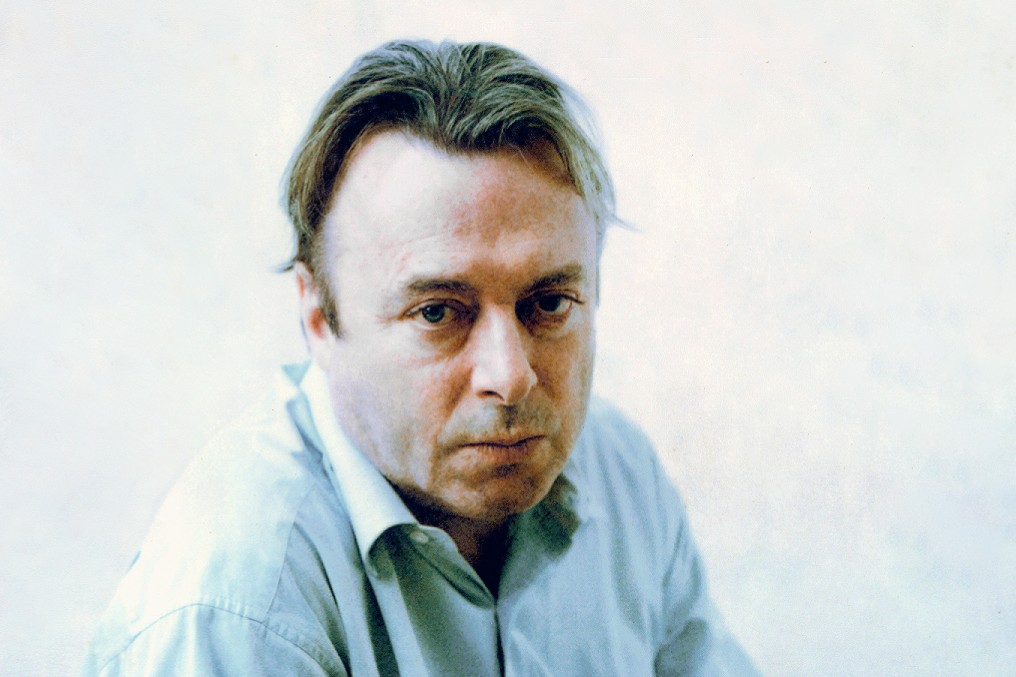

The only surprise is that it took so long: a new book by American Christian Larry Alex Taunton claims that Christopher Hitchens, the polemicist and critic who found his greatest fame a a scourge of religion, was in fact warming towards religion at the end of his life, perhaps even conceding to the truth of the Almighty.

These kind of deathbed conversion claims are almost as old as Christianity itself. Julian the Apostate, the last non-Christian Roman emperor, was rumoured to have died proclaiming to Jesus “Thou hast conquered, O Galilean”. From then on, almost everyone who had challenged or rejected the church has been posthumously defamed by religionists suggesting that in the end, they had come to the light. In the late 19th century, secularists Robert Ingersoll and GW Foote both wrote books exhaustively debunking deathbed conversion myths from Giordano Bruno to Thomas Paine.

Considering Hitchens’ fondness for Paine, the story is worth revisiting. Stories emerged in the late 19th Century that Paine had died howling and terrified, recanting not just his Deism (belief in a non-interventionist Creator) but also much of his political writing - a convenient line for reactionaries who would associate (probably rightly) his republicanism and atheism.

By the 1870s, US atheist Ingersoll had become so frustrated with this baseless lie that he offered a $1,000 to charity if one newspaper, the New York Observer could provide proof for its claim that Paine really had confessed and recanted in his final days.

The newspaper was unable to do so, and, triumphant, Ingersoll forced editor Irenaeus Prime to print the words "Thomas Paine died a blaspheming Infidel" .

Taunton’s claim that Hitchens was seeking God towards the end of his life seems to stem from time the two spent together travelling to debates, discussing the Bible. Hitchens was, indeed, fond of discussing the bible, or at least the King James Version. In an interview with Little Atoms in 2007, ahead of the launch of the best-selling God Is Not Great, he told us “I like My Cranmer and I like my King James, but I’ve never believed that any of it is true.”

Yet in the same interview, Hitchens was keen to point out that his approach to religion was more sympathetic than that of Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris et al.

Hitchens could understand why people wanted to believe in God, quoting Marx’s famous line “Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.”

Hitchens also related sympathetically to people’s belief in a personal relationship with God, citing the example of Bishop Hugh Montefiore, who had believed Jesus had visited him in his room when he was at school and convinced him to become a Christian: “It can certainly be said of Hugh Montefiore that the rest of his life he acted as if that had happened to him,” Hitchens said. “And I think it did happen to him, I just don’t think it happened. I think for him it was completely real, you just can’t make it real for me.”

This is, indeed, a long way from the Dawkinsish implication that believers are either stupid or lying.

Taunton, in his book, does not technically suggest that Hitchens ever found God, but rather characterises him as a “searcher”. And it is true that Hitchens was, for most of his life, a romantic in search of a cause, from Trotskyism to atheism to free speech to English literature.

But Taunton’s suggestion that Hitchens was a searcher carries its own code. To the Christian, carrying the belief in the objective truth of the Christian God, a “searcher”, coming to a question with an open mind and heart will inevitably accept the grace of God - the only real truth there is. This is the same formulation that Pope Francis used when he said of gay people “If a person is gay and seeks out the Lord and is willing, who am I to judge that person?” What that means in reality is if that person is open and willing, they will accept the church’s view that homosexuality is sinful. The self-same logic is applied by Takfiri jihadists who believe that anyone who disagrees with them is, in fact, rejecting the truth of God and can therefore be called apostate. It’s a line of (un)reasoning that never ends well.

If we wish to be generous, we could perhaps say that Taunton has confused Hitchens' public-school affection for the KJV and some of the trappings of the Church of England with some kind of leaning towards faith itself. Perhaps, even, it was the nostalgia of the Englishman abroad that perpetuated some enthusiasm for the words and sounds of the church, which he could easily disassociate from the actual believing part.

After Little Atoms interviewed Hitchens in Oxford in 2007, we all had a few hours to kill before our trains back to London. Having already spent most of the afternoon in an agreeable whisky haze, we asked Hitchens if he’d like to join us in a pub while we waited. “That’d be nice,” he said. “But actually I really want to go to Evensong.” And off he went, a psalm on his lips perhaps, but not a hint of God in his soul.

For more on the history of deathbed recantation myths, read this New Humanist article from 2005