23 April was the anniversary of Shakespeare’s death. Among the many achievements of the great bard, Shakespeare was our most prolific wordsmith. He churned out hundreds of new expressions and words that we now take for granted: “sorry sight”, “what the dickens”, “bedroom”, “belonging”, “ebb and flow”, “laughing stock”, “sea-change”, “star-crossed” and on and on and on. Before him the English language seemed barren, and thought by the upper echelons a poor cousin of French or Italian, a language that lacked the range and depth of Greek and Latin. He helped change all that.

Language not only reflects the world it has to describe, it also shapes it. Think, for example, of “robotics” – a word coined by science fiction writer Isaac Asimov. His writing went on to inspire nerds across the world, who in turn actually made robotics a reality.

The modern coiner of words and phrases isn’t literature – it’s the internet. In his recently published book Netymology Tom Chatfield explains the origins of 100 net-based words, from “apps” to “zombie computers”. Geek, he explains, originally meant “fool or freak” in Middle English. Wiki means “fast” in Hawaiian. The Streisand Effect occurs when trying to stop something being shared online has the effect of making more people see it. The Scunthorpe Problem refers to when “words and phrases fall victim to machine filth filters thanks to unfortunate sequences of letters within them”.

But I’m more interested in these phrases' return journey: the way a growing amount of internet based language is escaping its online straitjacket and creeping into mainstream use. Those phrases or words which had a solely net based meaning, but have become so widely used as that they are now describe something offline too. So in keeping with the times I’ve created a generic, non-specific list of internet words and expressions that have invaded our offline language.

I of course “crowdsourced” this list, asking Twitter users to send in their ideas. Crowdsource was first coined by Wired Magazine’s Jeff Howe in a 2004 article. It refers to the growing ability of people to more efficiently complete a task by sending it out to lots of people. It’s not specifically internet related of course, although the net has made it far easier to do. Wikipedia being the best example, but Google, given its data is based on our search choices, is also to some extent crowdsourced.

To take something offline originally meant “let’s talk about this when we're not on the internet”. This is often very wise, given you might not want everyone else knowing what you’re discussing. These days, however, its more common use is to suggest such-and-such issue be talked about after the current meeting. You don’t need to be online to take something offline anymore.

Hacking of course pre-dates computers. But its use in the digital world now far outstrips its origins of chopping or cutting. Back in the Sixties and Seventies, programmers at universities would “hack” together solutions when their computers weren’t working well. While it’s had a bad rap lately – its more criminal side frequently in the news – it seems to be heading back to its more noble origins. People now routinely talk about “life hacks”, which are quick fixes for solving problems or increasing efficiency in your daily business. People who do life hacks are very important and busy people indeed – far too important and busy to do things like make to-do lists or keep their trainers clean the normal way. They have to “life hack” it instead.

Multi-tasking is such a widely used phrase today that it’s easy to assume it predates computers. In fact, multi-tasking refers to computers scheduling different tasks for processing to increase productivity. Now, of course, everyone is a multi-tasker, and usually multi-tasking with devices that are themselves multi-tasking.

In computer programming speak “to fork” something means to make a new unique copy of software from which you can then work on and adapt without damaging the original. But I now hear people talking of “forking” documents, ideas, and anything else they can lay their hands on.

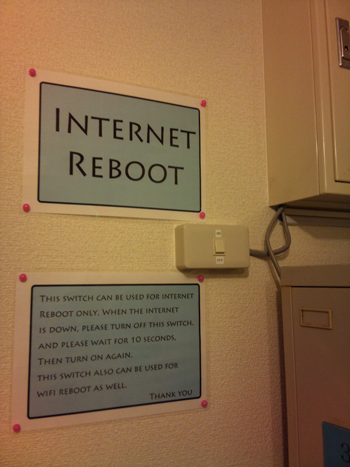

This refers to the process of resetting the computer, and causing the operating system to reload. But it is now used to describe the process of humans rebooting. Going on holiday doesn’t quite seem enough nowadays: we need to shut down entirely. Effectively, this means having a long break to allow our brains to reset and reload, often in the hope that this might improve matters. While turning computers off and on again does actually seem to work, it’s not clear the same approach works well on humans.

In the good old days, when people were busy they said they didn’t have time. Now they don’t have “bandwidth”. Bandwidth, which means the bit-rate of information capacity, is sort of like time, but more sophisticated. People without bandwidth have time – we all have time – but they have too many other processing jobs running and so subsequently lack the required computing power to take on further tasks. Not having sufficient bandwidth may also be a sign that some life-hacks are in order.

This originally referred to the fishing techniques of allowing a baited line to skim a surface of water, and not the Nordic cave dwelling ogre. It was first dropped online in 1992, when experienced users in the Usenet group alt.folklore.urban started “trolling for newbies," posting something that would coax the new users into making themselves look foolish while simultaneously letting the initiated know exactly what they were doing. It then morphed into shorthand for any and all nasty behaviour online, and increasingly is used offline too, referring to any practical joke designed to make someone look silly.

I've included text-speak mainly on account of its ubiquity. The abbreviations aren’t new of course: The first recorded use of “OMG” was by Winston Churchill in a 1917 letter. But a lot of the early emoticon and abbreviation talk came from early bulletin board systems and Usenet groups of the early 90s, where expensive dial up costs put a premium on brevity. Yet these handy time saving devices are now being said out-loud by people with terrifying indifference. ‘Oh, Emm, Gee’ is now heard far more often than ‘Oh My God’ which sort of misses the entire point.

It’s come a long way, the humble hashtag. As Chatfield explains in Netymology, it was originally used in 1920s America as a shorthand for pounds (the weight) but was then introduced by technicians at Bell Labs in the 1960s as a generic function key on their new touch tone telephone. Now every campaign, movement or event needs its hashtag so that others can discuss it. Whether a sporting event, public debate, television show or political campaign, if there isn’t a hashtag it hasn’t really happened. Most bizarrely, it is now common to see people holding up banners and posters in real life with hashtags written on them – this was a common sight during the Arab Spring as protesters tried to rally the digital mob to their aid. I now frequently hear people saying the word hashtag to describe an emotion or feeling, as in: “I’m well tired today: hashtag need a coffee”. To top it all, and reason enough for hashtag to come top of the list, in 2012 someone actually named their child Hashtag. This despite the fact that the word hashtag still doesn’t actually seem to mean anything in particular.

The important part of all this is the way in which these words, and the ideas they contain, carry with them a particular way of thinking and behaving. Words always frame thought, and all this multi-tasking with our limited bandwidth, all this abbreviation and rebooting, it all reflects a peculiar state of affairs: that we are starting to think and act like the computers that we spend so much of our lives with, and who seem to be getting better than us at doing lots of things. It’s the language of efficiency, connectivity and processing systems. Abbreviate everything, hashtag it, send it out to the crowd, and reboot when it our bandwidth starts getting too limited. I hope I’m wrong about this, since it feels like an ill wind which blows no good. Or perhaps I’m just gilding the lily.