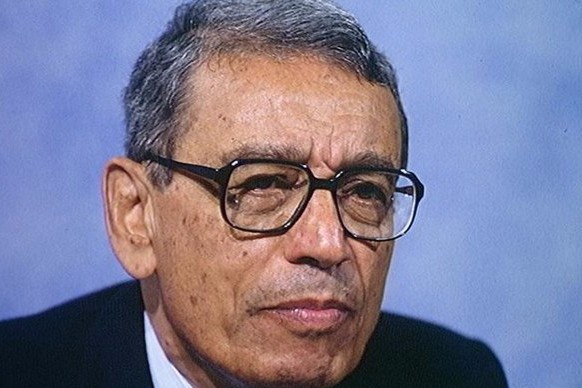

Scion of a distinguished Coptic family, grandson of an assassinated Egyptian prime minister, a Fulbright scholar with a doctorate from the Sorbonne — there’s no doubt you’d have done well to have Boutros-Ghali sat beside you at a dinner party.

He took office as Secretary General of the UN on the first day of 1992. The Soviet Union had dissolved on 25 December 1991.

And with the United Nations no longer shackled by the Security Council vetoes of the Cold War, there was a chance — with post-Cold War conflicts just about to break out all over the globe — with proper leadership, it could finally act to ‘restore international peace and security’ as Chapter VII of its Charter envisaged.

Let us approach his tenure through the counterfactual. With the Cold War just ended, how might he have done differently to put the last, best hope of mankind in centre stage for dealing with the bloody conflicts of the ensuing years?

For one, don’t approve secret $26 million arms deals to the Hutus in 1990 when they are making fairly public plans for genocide.

This was on the eve of his election to the top post, when he was Egyptian Foreign Minister. In context, Rwanda, one of the world’s poorest countries, was then bankrupting its economy spending $112 million on arms imports.

It was the third largest importer of weapons in Africa, according to Linda Melvern in her 2004 book Conspiracy to Murder.

But, you say, in gentlemanly fairness to Boutros Boutros-Ghali, perhaps the army of Rwanda simply planned use these 16,000 mortar shells, 3,000 artillery shells, and more than three million rounds of small arms ammunition to hold a truly epic Trooping the Colour.

This would be gentlemanly indeed. Seeing as a 1990 edition of Kangura, a race-hate magazine bankrolled by the governing MRND party, had just published the lovely “Hutu Ten Commandments”.

It included “The Hutu should stop having mercy on the Tutsi.” And “The Hutu must be firm and vigilant against their common Tutsi enemy.”

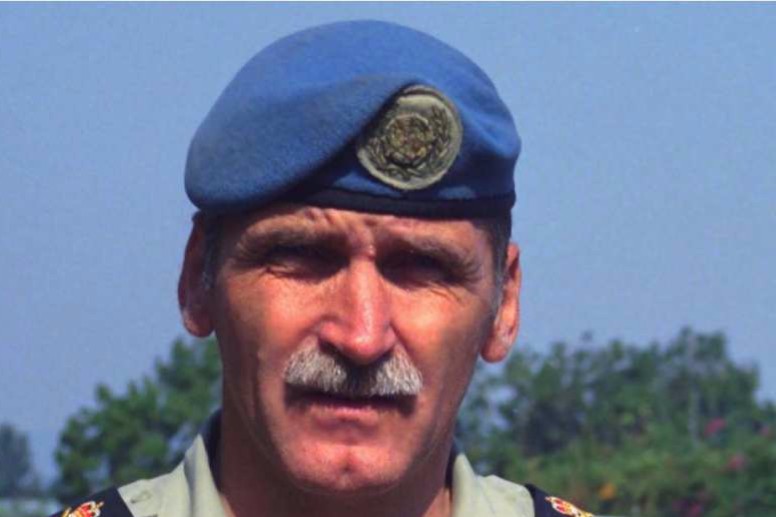

Fast forward to Boutros-Ghali’s tenure at the UN itself. In Rwanda, on 10th January, 1994, Canadian General Roméo Dallaire — commander of UN peacekeeping forces there — obtains intelligence from a former member of the President’s security guard about the planned genocide.

Cabling New York, he tells his bosses his informant “has been ordered to register all Tutsi in Kigali. He suspects it is for their extermination.”

Two days later, Dallaire receives a fax from the UN Secretariat in New York telling him not to seize the stockpiled weapons, because it was not in the UN peacekeepers’ mandate.

Boutros-Ghali had chosen as his special representative the brazenly pro-Hutu Jacques Roger Booh-Booh, and it was Booh-Booh, not Dallaire, who had his ear. The Secretary General subsequently went to the UN Security Council and lied, saying all parties remained committed to the peace process.

Dallaire still suffers from posttraumatic stress disorder, and has attempted suicide four times.

But Boutros-Ghali could be hawkish, too, when this was precisely the worst course of action.

In Somalia, he demanded a US helicopter attack on a meeting of leaders of the Habr Gidr clan on 12th July 1993.

The elders were meeting to discuss a peace initiative, proposed by retired Admiral Jonathan Howe, head of the UN Mission in Mogadishu. The majority of the elders were disposed to make peace.

The helicopter attack put paid to that, and the deadly October Battle of Mogadishu (immortalised in the film Black Hawk Down) was the result.

Boutros-Ghali was not exactly well placed to be a neutral arbiter in Somalia.

As Egyptian foreign minister, Boutros-Ghali was a major supporter of Somalia’s dictator Siad Barre. In 2001, the United Nations Development Programme writes Barre had “one of the worst human rights records in Africa”. And Aidid overthrew Barre.

Aidid, head of the Habr Gidr, was convinced the Secretary General nursed a vendetta against him from before.

Right enough, then, poor luck with Rwanda and Somalia. It just so happened, compromised by his past as an Egyptian diplomat, Boutros-Ghali was precisely the worst person conceivable to play neutral mediator for two bloody crises in Africa.

But everybody has a past. Regrettably, he didn’t distinguish himself in the break-up of Yugoslavia, either.

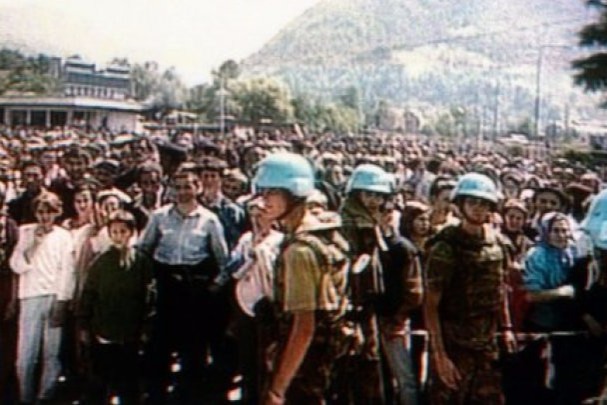

He had set himself out to confront the North-South divide as Secretary General, and Bosnia to him was a distraction. The Balkans he called ‘a rich man’s war’, and he said there were others where the ‘total dead was greater’. In Sarajevo in December 1992, he told the citizens, in the middle of a siege, he could give them a list of ten places with worse problems. It’s not quite diplomacy, whatever his job title.

When the massacre of 8,000 Muslims took place within a UN “safe haven” in Srebrenica, Boutros-Ghali went ahead with a visit to Africa, and called Srebrenica "a village in Europe".

He steadfastly opposed air strikes in Bosnia against Serbian forces — just as in Rwanda, he ordered the pullout of the peacekeeping presence at the height of the genocide.

In 1996, Foreign Affairs magazine summed up the episode with an article titled The Mark of Bosnia: Boutros-Ghali’s Reign of Indifference. It was the last year of his tenure.

He remains to this day the only Secretary-General not to be elected to a second term in office. A nicer man could not have been a worse fit for the most important job of the last quarter-century.

Symbolising in his own person the UN's own decline into irrelevance, he tottered after to be secretary-general of La Francophonie, and a juror on the Chirac foundation's prize.

But the damage was done, to the dead of Rwanda, Somalia, and Bosnia, and the credibility of the United Nations.

Think of Syria and Ukraine. Think how often you’ve heard the voice of the United Nations. And thank Boutros Boutros-Ghali.